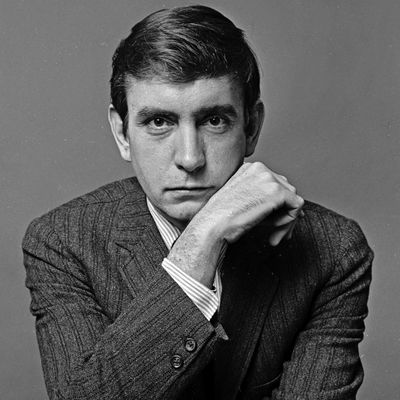

Even from the beginning, Edward Albee was rarely photographed smiling — or, rather, photo editors seldom chose to print any smiling portraits that might have been taken. The truth was that he had bad teeth, but the glower went along with his reputation as an angry young man, and seemed to say: What is there worth being happy about, anyway? By the time he was an older man, when I met him, he’d grown so deeply into his implacable face that it seemed like one of the African masks that lined his Tribeca loft; even his mustache pointed down. And yet, of the foundational 20th-century American playwrights — the others were Eugene O’Neill, Arthur Miller, and Tennessee Williams — he was, in his writing, by far the funniest. All four men had essentially tragic outlooks, but Albee’s was howlingly so; he alone saw humanity’s struggle to understand itself as a cosmic joke.

I got to know Albee, who died on Friday, over the course of six interviews between 2004 and 2012. During that time he completed at least two new plays and minutely oversaw productions of many old ones. But he also aged from 76 to 84, grieved the death of his longtime lover, had open-heart surgery, fell hopelessly in love with a 23-year-old straight guy, and otherwise endured several proof-of-concept losses. By the time of our last interview, he even found his mental machinery glitching a little; what he said was not always exactly what he meant. Still, he trusted his own dialogue so completely that he was willing to consider the aptness of even an errant utterance. At one point, meaning to say “They are not me” he instead said “I am not me,” then ran with it, delighted to discover in the mistake an element of his actual philosophy: Identity is an illusion. He remained as alert as a diamond merchant to the cut, color, clarity — and the sometimes enhancing imperfection — of words.

No wonder; he had been their early and frequent victim. His parents, who he claimed bought him from an adoption agency for $133.30, ceaselessly made it clear how much they regretted their purchase. His critics were no less regretful for having taken him up so young. Soon after the enormous success of The Zoo Story (1958) and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962), many turned on him with the furious disappointment of Dad discovering that his hoped-for manly little man is gay. Ridiculously, some started whispering that Virginia Woolf was really about homosexuals — homosexuals who apparently have hysterical pregnancies. Soon, the bigotry no longer needed to be whispered. In a New York Review of Books takedown of the mysterious Tiny Alice (1964), Philip Roth condemned Albee’s “ghastly pansy rhetoric.” The headline, inevitably, was “The Play That Dare Not Speak Its Name.”

Albee lived publicly as a gay man long before almost any other major playwright dared, even the flamboyant Williams. This fell naturally from his concept of the imagination as the true and only responsible parent of the self. (He obviously had to reject his adoptive parents, and never sought to know his biological ones.) He often told me, because I refused to believe him, that he did not so much write his plays as transcribe them from his imagination; he said he would find himself “knocked up” with an idea, which then, after a few months’ or years’ gestation, he would birth full-grown. (He also claimed not to rewrite established works, though in fact he did, at least a little.) The discovery of his gayness was thus tantamount to living openly as a homosexual; the idea made it so, and prevented any backtracking. The discovery that he was an alcoholic — a discovery many others made about him long before he did — likewise resulted in a complete, cold-turkey sobriety.

Which is not to say he identified as a gay (or drunk) playwright. He was, he said, “a playwright who is gay.” And though that aversion to identity politics in his artistic life led him into unnecessary conflict with natural allies, he was not, even much later, closed to new ways of thinking. When I interviewed him for an event at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center in 2005, he responded to my question about marriage equality with a rote dismissal common to his generation of gay men: Why would we want the right to participate in a degraded religious institution that had no business in the public sphere to begin with? But he was showboating; his antagonism toward religion was always a crowd-pleaser. Later, a lawyer I know approached Albee and carefully explained the woolliness of his thinking. By 2008, when I asked him the same question in an interview at the Times Center, I was surprised to find him now toeing the line. More than toeing it: stamping on it hotly. In 2011 he won the Lambda Literary Foundation’s Pioneer award.

Of course he’d won every other kind of award already, including three Pulitzers, for A Delicate Balance, Seascape, and Three Tall Women. None of those plays had gay characters or themes, though I suppose Roth would have identified in at least two of them the pansy rhetoric he so dreaded. What was the threat? It would be as foolish to psychoanalyze Roth, of all writers, as it was for him to psychoanalyze Albee, but it’s hard not to notice the homosexual panic. Albee’s coupling of verbal wit, which derived from Wilde, with existential inquiry, which derived from Beckett, read to Roth as a form of miscegenation, or even rape. And then, too, perhaps Roth and his ilk — including the critics Robert Brustein and New York’s own John Simon — were not quite ready to have the great-writer laurels descend so far from the dour lady-killer Wasp St. Eugene. A Jew like Miller was fine but enough was enough. Who knows what opening the door to the pansies (Williams, Albee) might presage? Women? Blacks?

Albee, after a long period in which his new work was routinely savaged along such lines, prevailed. I don’t just mean the way his reputation was revived in 1990 by Three Tall Women, which suddenly turned him into a great man of the theater as if he hadn’t always been one. I also mean that he lived and wrote well long enough to get a fresh hearing from a new generation of audiences and critics. Even huge disasters turned out, upon reevaluation, to be candidates for lasting importance. (The Signature revival of The Lady From Dubuque, which had closed after 12 performances in 1980, was stunning in 2012.) As a result, it seems certain that his catalogue of some 30 plays will be read at least as long as O’Neill is, or Roth is, and possibly a dozen — an astounding proportion of them — will be regularly performed.

That doesn’t mean they will be understood, but I’m not sure Albee cared about that. He said that theater had a responsibility to hold up a mirror to humanity, not to explain it. Anyway, explaining was a bore, and another of the theater’s responsibilities, he said, was to entertain. The two things together — inexplicability and amusement — produced his characteristic tone of witchiness. In his plays and in his public persona you most often glimpsed him dodging behind paradoxes and disappearing into syllogisms. Q&As with him were more like Q&Qs; many a time he merrily led me on wild-meaning-chases, at the end of which I found nothing. I think it was the second time I interviewed him that he asked, as we started, to look at my tape recorder, which (I explained) was actually a digital recorder I’d recently started using. He held it for a moment and then gave it back. Of course, when I got to my office, the entire interview was gone from that point forward; Tonya Pinkins, whom I had interviewed a week earlier, took over. Had he cast a spell? Deliberately sabotaged me? Jangled the electrons by force of will? In any case, I called him, mortified, to explain what happened, and he said, “Just come back tomorrow and ask the same questions. I’ll give you completely different answers.” Which is exactly what he did.