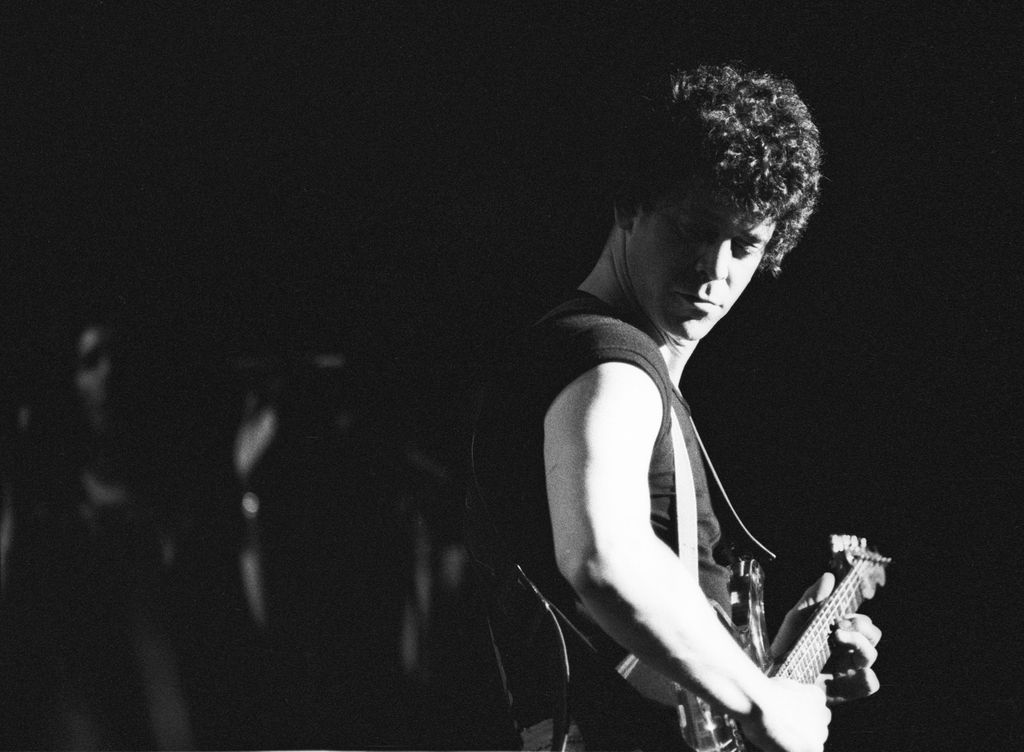

Way back in high school, Lou Reed formed a band, got a record deal, and even released a promising single. But his dyspeptic nature alienated his friends. They never made a follow-up. When his talents finally found a place worthy of their ambitions, it was in a group called the Velvet Underground, in partnership with a stalwart avant-gardist named John Cale. Their alliance created two of the most influential albums in rock history — and then Reed summarily fired Cale.

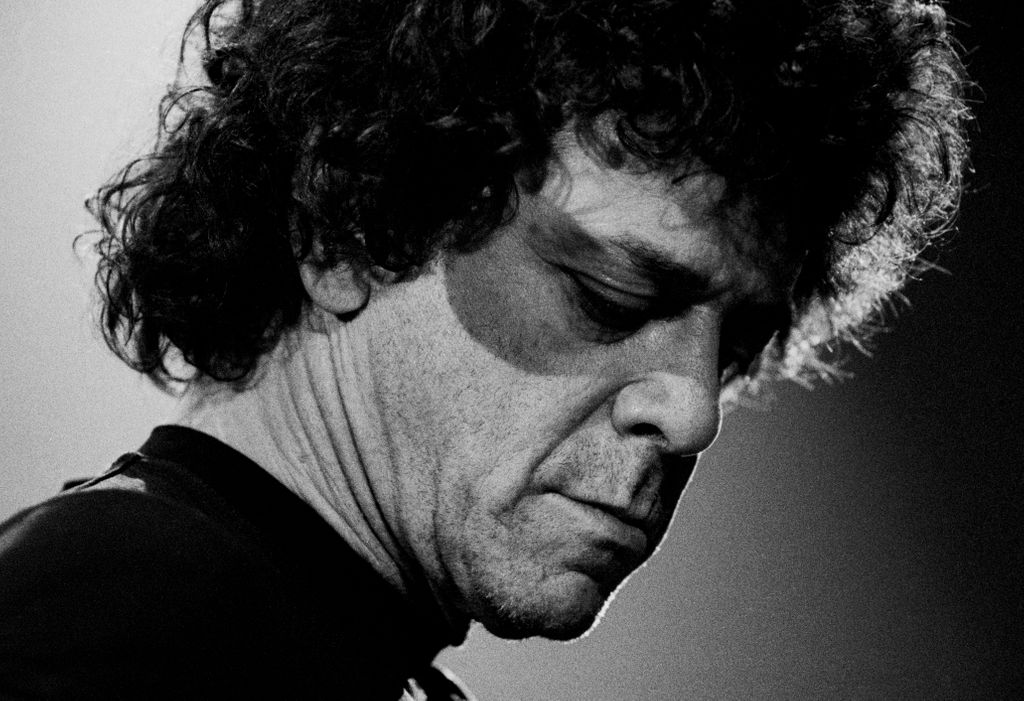

That’s how Lou Reed’s career went. He was never happy; there was always something to attack. Humanity brought out the worst in him, and he returned the favor. His peremptory demands, imperious and selfish nature, abruptly withdrawn support or mentorship, inconsistent vision, and overall inability to play well with others made his life a checkered history of failed alliances and artistic misfires. Few personalities — particularly as one as protean and occasionally as brilliant as Reed’s — can be summed up in two syllables. But if you were to do a word cloud of memories of Reed in the various volumes that have been published on his life, the word asshole would turn up in surprisingly large type.

Yet it was still wrenching to hear of his death, of liver cancer, three years ago this October. He’d found some peace in his long, late-in-life relationship with Laurie Anderson, a welcome note of resolution and union to a decidedly discordant career. Since then, we’ve seen two biographies, with two more expected in 2017. And besides that, what must have been a heroic bit of corporate rightsmanship has produced a comprehensive remastered box-set collection of his seminal work, everything from his groundbreaking RCA early solo years (Berlin, Transformer, etc.) to his slightly more audience-friendly Arista releases that stretched into the mid-’80s (ending with Mistrial,in 1986).

For all the gems in his work, his biographers, delving through the tumultuous events in his life, can’t cover up their subject’s flaws. One is by Howard Sounes; titled Notes From the Velvet Underground, it displays the benefits of no-nonsense shoe-leather reporting, as did Down the Highway, his clear-eyed exposition of Bob Dylan’s life and career. (Sounes was the first to get the names of Dylan’s children correct.) Surprisingly, though, the keeper is Dirty Blvd., by Aidan Levy, a writer with a forceful, poetic bent and cultural antennae that quiver ecstatically at the signifiers in Reed’s aesthetics and those of the complex culture around him. As you read it you notice, again and again, a modest reportorial zeal that uncovers key mysteries of Reed’s life. It loses its momentum (as Reed’s career did) in the last 20 years of his life, but all in all it’s a virtuoso rock biography.

Both books hide in plain sight a cautionary tale for all readers, and also the authors of two other in-progress biographies on Reed due out next year. How to balance the antics, often cruel, senseless, and self-destructive, of their subject, against the work? Some people have no problem with this dichotomy; it’s easy, they say, to separate the person from the art. In Reed’s case it’s harder. One, as I said, is that that there’s more than a little evidence that his personality actually compromised his work and made his legacy the paltriest of all the great ‘70s rock stars. And two, because underneath that hostility lies an affliction that perhaps deserves to be foregrounded when we talk about Reed: a mental illness that from a very early age convulsed his life.

Like Bob Dylan, Reed left a modestly prosperous Jewish upbringing and reinvented himself — re-created himself, perhaps — in an outlandish subculture. The man who would become the defiant chronicler of a drug-and-sex-drenched demimonde came of age in the mean streets of a comfortable neighborhood on Long Island and then Syracuse University. Later he would demonize his father, who was said to be rigid, and would revel in the disconnect between the middle-class experience of the time and the adventuresome new cultures he and others like him embodied. (One notable example is the song “Families,” from The Bells.) But in many ways his family supported his talents. His parents let his high-school band practice in the basement and signed his record contract when he was underage — not to mention dutifully driving him off to college and, one is sure, funding his stay there as well.

Today we understand that both he and his family were the victims both of biology and of the times. It’s not clear exactly what variety of mental illness Reed suffered from. Later in life, his sister, who became a psychotherapist, said Reed had been tormented in elementary school and suffered from anxiety and panic attacks. As he got older, socialization problems led to antisocial and inappropriate behavior. Throughout his life he was called a “jerk,” an “asshole,” a “dick.”

Accounts from his high-school years teem with examples. One friend remembers being with Reed and some other male friends when some women came over to their group. “Fuck you,” Reed said to them. This was in the mid-1950s. “You simply didn’t talk that way to women at the time,” the friend recalls. There’s another story of Reed going to pick up a woman for a first date. At the door, a younger sister came sliding down the stair railing. “Do you always masturbate on the banister?” Reed asked the girl, and that was the end of the date.

Sex is not an anti-social behavior, of course, but in this realm he was acknowledged to be precocious. While most teens dated, fairly innocently, in their social circle, Reed’s male friends knew that Reed dated older, more experienced women from nearby towns. And there can’t have been too many suburban teens in the 1950s who worked tables at the local gay bar. Friends were taken aback at stories Reed wrote even in high school that depicted homosexual encounters, sometimes violent ones. It seems that Reed was having relationships with men at a fairly young age along with women. According to Reed’s sister, their parents were socially liberal and would not have demonized homosexuality per se. Reed first went to college at NYU, but lasted only months before having what might have been a nervous breakdown. You can imagine a kid with Reed’s bluntness matter-of-factly telling a psychologist about his gay interactions, which given the times would probably have had unsavory aspects. In any case, his parents, on a doctor’s advice, allowed him to be subjected to two dozen electroshock-therapy sessions.

This medieval process amid the outward calm of the Eisenhower years is a potent metaphor for Reed’s singular artistic obsession. What we think of as “the strange” not only walk among us but are of us, creations of our fear and hate.

His band the Jades in high school had a record contract and a minor local hit. The band didn’t survive. “He was very tenacious, very focused, but he was a dick,” recalled a bandmate. After high school, Reed eventually made his way to Syracuse. For the rest of his life he made much of his relationship there with Delmore Schwartz, who had been a celebrated American poet. (Ah, the time when that meant something.) At Syracuse, Schwartz was already in the throes of a death spiral of alcoholism and schizophrenia that would destroy his life and a few years later see his corpse lying unidentified in a New York City morgue for days. In college, Reed showed himself an aesthetic radical a few years ahead of the Zeitgeist, earnestly writing songs on a folk guitar, outpacing all his friends when it came to drugs, playing in bands, hosting a radio show, and even creating a literary magazine. He collected influences like a magpie, from Ornette Coleman to William Burroughs. (Levy notes, bracingly, that Naked Lunch includes a corps of doctors intent on eradicating homosexuality.) Reed came out of college with a degree, a heroin habit, and hepatitis … and went back to live with his parents.

He ended up a writer in an ersatz song factory that created anodyne knockoffs of the hep hits of the day. A chance encounter with another musician there led him to a new life in a fetid unheated apartment in Manhattan. John Cale had already had a remarkable career; he was a child viola prodigy who managed to take himself from a village in Wales to being mentored by Aaron Copland to working with some of the major talents in the capital of world culture. (Among other things, he had accompanied John Cage in a two-man, 18-hour-long Satie performance.) Reed and Cale connected. You could find them, on odd days in 1965, acoustic guitar and viola in hand, on a street corner in Harlem, standing amid the varied passersby to sing their own songs. One of Reed’s went like this:

Heroin

It’s my life

And it’s my wife

They formed a band with a guitarist friend of Reed’s named Sterling Morrison and a friend of his named Maureen Tucker, who played tom toms, standing up. On top of this Reed played a sometimes cacophonous guitar, Cale a perfervid viola. No one in the band seemed to care in the least what an audience might want to hear. Local club owners found the band rebarbative; it must be considered sheer fortuitousness that a couple of deputies to Andy Warhol chanced to see them. The great man himself took in one of the group’s shows. Soon the Velvets were the house ensemble for Warhol-sponsored happenings like UpTight and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. The band members slipped easily into the high jinks of the Factory, the polymorphously perverse playground for the soi disant underground artistes of the day. In one sense, Reed had found a home to replace the one that had scarred him; at the Factory, his personality was celebrated, not assaulted. Please Kill Me, the classic oral history of punk by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain, contains this winsome memory, from Warhol photographer Billy Name, about the conclusion to a night of partying: “Lou would just jerk off, get off, and get up to leave, so I had to say, ‘Hey, wait a minute. I didn’t come yet.’ So Lou would sit on my face while I jerked off. It was like smoking corn silk behind the barn, it was just kid stuff.”

Warhol’s management did not lead to rock stardom. The history of the Velvets is highly amusing and flooded with passing interactions with the celebrated artists of both that day and the days to come. But it is in the end one of clueless business dealings and unrealistic expectations. Trips to California were disastrous; “I fucking hated hippies,” said Tucker. And besides Reed’s contrary nature, the band had to deal with ex cathedra Warhol dictates. One was giving the band a new singer. This was a humorless German model named Nico, who’d grown up amid the ruins of the Second World War and retained a slightly overenthusiastic allegiance to what in this context might be called the fatherland. Forgive the dated Neil Simon reference, but the result was a lot like the plot of The Star-Spangled Girl, only with a Nazi. She became intermittently involved with both of the Velvets’ principals. She and the towering Cale in their sartorial splendor stood out even among the Factory’s quotidian freak show: They looked “like they were in the Addams Family,” Iggy Pop once said.

Reed’s waspishness found its unhappy match there. According to Cale, who might be settling grudges, Reed couldn’t keep up with the verbal blood sport of the scene. Cale recalled a Velvets rehearsal where Nico, habitually, came in late. Reed greeted her coldly.

“Nico simply stood there,” Cale said later. “You could see she was waiting to reply, in her own time. Ages later, out of the blue, came her first words. ‘I cannot make love to Jews anymore.’ “

Rock legend celebrates the Velvets’ poor sales as an indictment of the industry in particular and society in general. But the period, after all, had a lot of adventuresome music that sold well. And this band, with its inconsistency, odd production values, and wildly clashing vocals (Reed’s confrontational delivery and Nico’s stentorian one) didn’t make for songs that sounded good on the radio.

Somehow, the band recorded four albums that remain beloved and, in parts, persuasive to this day. Velvet Underground records were innovative in the realms both of noise and quiet, in essence making the argument that great rock ’n’ roll didn’t have to sound good on the radio. In softer moments Reed was capable of putting together simple, emotionally resonant ballads whose faces of calm hid dark lyrical tropes — “Femme Fatale” and “Pale Blue Eyes” among them. His lyrics were more abstract and yet more colloquial than those of any figure writing at the time. Here he is at his best, in the song “I’ll Be Your Mirror”:

When you think the night has seen your mind

That inside you’re twisted and unkind

Let me stand to show that you are blind

Please put down your hands

’Cause I see you

I’ll be your mirror

Again, this is Reed’s most natural subject: the experience of the unwanted and the despised. Some of the words we have today — bullied, gay, trans — didn’t really exist as such back then. Reed thought that feeling “twisted” could warp someone’s very identity, their own understanding of who they were. “Please put down your hands” may be the key line here, a powerful image of someone covering himself up, erasing himself. “You” and “your” appear in every line, as the singer tries to pair their humanity, replacing the other’s dark self-image with the one she sees. Isn’t this one of the most profound love songs of the era?

And then there’s the noise. In rockers like “Heroin” and “I’m Waiting for the Man,” the band’s rudimentary chordage, shuddering velocity, previously unheard atonalities, and hypnotic effects took rock ’n’ roll to new extremes. Reed’s subject matter, too, in these songs was wild, nasty, unheard of. To do violence to Marianne Moore, Reed was writing songs about imaginary undergrounds with real circle jerks in them. “Sister Ray” — transexuality proudly signified in the title — sounded a bit like Dylan’s “Maggie’s Farm,” if “Maggie’s Farm” were sped up, overlaid with a maelstrom of clanking guitars, and played for 18 minutes. The song’s celebrated, insistent chorus includes the words, “I’m searching for the main line / I said I couldn’t hit it sideways,” a sordid reference to heroin. But this is to overlook another phrase that for some reason hadn’t yet appeared in the collected works of the Beatles, the Stones, or the Beach Boys: “She’s too busy sucking on my ding dong,” repeated several times for effect.

In time Reed jettisoned Nico and Warhol and finally Cale, losing some friends on the scene on the way. “Lou was brilliant, but he was an asshole,” said one. We forget today, when the Velvets are celebrated as one of the first great uncommercial bands, that Reed wanted to be popular. This dichotomy of ambitions — despising society and yet craving its support — tattooed Reed’s career. In search of this chimera a reconstituted band moved to another label and tried to get even more into a pop groove. Loaded, the group’s final album, was supposed to be “loaded” with hits. A lot of it shows the band trying too hard, but there are two signal Reed songs here, “Sweet Jane” and “Rock & Roll.” In “Sweet Jane,” particularly, Reed’s effortless riffs and unbounded lyrics capture a new transsexual normal with giddiness and joy. His vocals do everything to drive the point home: hepcat scatting at one point, howling at another, maneuvering some deceptively difficult rhythms at yet another, but always somehow returning to embrace those chugging chords. It’s everything a rock song should be.

The VU was Reed’s band now; he had just recorded his two greatest songs. But its uneasy history and years of bad decisions made his position seem less like an opportunity and more like a trap. Or so he told himself. For reasons too boring to go into here, the Velvets hardly ever had played live in New York City and didn’t have the large fan base there you’d expect. The band was booked for a series of gigs at tiny Max’s Kansas City when Reed stopped showing up. The Velvets slipped into history. Reed, again, went back home to live with his parents.

What you might call Reed’s classic years as a solo artist began with a self-titled debut in ‘72 and lasted for a period I would argue was somewhat shorter than the new boxed collection has it: a dozen or 14 albums in all, and hardly two sporting a similar sound. His wishy-washy debut, with nothing like a song like “Sweet Jane,” was recorded in London with session players from the progressive rock band Yes and appreciated by no one. To support it, for some unaccountable reason, he went out on tour backed by four teens from a local high school. Within a few weeks, Reed was drinking himself into a stupor and playing songs onstage in the wrong key.

Lucky for Reed, a young British wannabe star had connected with the Velvets’ music early on. He’d grown up to be David Bowie; fresh off Ziggy Stardust, the new sensation said he would oversee Reed’s second solo album. Transformer became a sign of what Reed could do when focused. With several of Reed’s more durable songs and a production schema from Bowie that is both fairly consistent and occasionally delightful, Reed lays down a passable claim to greatness here. There is poetry in many of the songs and real drama in the same places. “Satellite of Love” is a good example, a delicate melody disguising a bleak, almost savage reality, all ameliorated by a light in the sky reflective of both hope and isolation. A new tic in Reed’s writing, a stagey theatricality in some of the arrangements, actually works here, in the song’s bridge. “Perfect Day,” another seemingly romantic song on Transformer, also contains a landmine in its coda. Aidan Levy, in Dirty Blvd., is at his best when he limns the way a song like “Perfect Day,” dedicated to Reed’s first wife, Bettye Kronstad, contains both the emotion of their connection and plain signs of its eventual fracture.

Bowie also oversaw the utterly sensational production assemblage that is “Walk on the Wild Side,” Reed’s matter-of-fact recitation of the lives of some of his erstwhile associates in the Factory. The result is a grand American tale, as full-bodied in its humanity and reach as anything by Chuck Berry and Bob Dylan, and John Ford and Whitman besides — a dramatic portrait, etched with personal details, of a country where all roads lead to New York City, home of “a hustle here and a hustle there.” That wouldn’t matter without the music: the wild conception of the chorus (“And the colored girls go / ‘Doo do-doo do-doo…’ “); the doubled bass line; the unexpected, languid, and entirely right sax solo to take the song out. Here again, Levy has a penetrating riff on how Reed takes the musical base of the song — two notes, nothing else — and builds a multivarious musical and thematic epic on top of it.

Thanks to Bowie, Reed had a worldwide hit single. Like many of his fellow ‘60s holdovers — Young, Dylan, Clapton, Stewart, Townshend, others — he could have maneuvered the 1970s, plugged into an intelligent and ever-more-monied new audience, and been the artist he wanted to be. And here’s where the disinterested reader’s break with Reed comes.

Reading about the next ten or 20 years of his life separates one, fundamentally, from the subject of the story. We know that Reed suffered from some sort of mental illness, we know the electroshock sessions were traumatic, and we know that in many ways he probably couldn’t help himself — and turned to drinking and drugs for respite. But the mundane litany of the stories over time in a way subsumes him; neither biographer relishes the stories or makes them lurid, but after a while — there’s no other way to say it — you start to dislike Lou Reed. In both Sounes’s and Levy’s books, conflicts come up again and again. Reed is angry at producers, record-company executives, managers, collaborators, and his lovers. He has writer’s block one minute and hits his wife the next. (Kronstad says he gave her a black eye.) There are failed marriages, failed romances, failed albums. The accomplished producer Bob Ezrin conceived Berlin and was its nurse-maid. He ended up with a nervous breakdown and Reed didn’t work with him again. Kronstad, tired of the heroin, the drinking, and the violence, left him, got lured back, re-experienced his nastiness, and left him again. (He’d turned into a “monster,” she said.) There were sidemen and students who betrayed him, reporters who didn’t understand him. (For a while, Reed tried to mock interviewers à la Dont Look Back–era Dylan, but he was never able to pull it off.) His weight bloated; Levy, noting that and the androgynous makeup he liked, calls it Reed’s “sad panda” look. He drank and drugged himself and his marriage into a stupor and sometimes kept crowds waiting for hours as he sank into self-pity. There’s no rock ’n’ roll grandeur or craziness in these stories, just a somewhat sad tale of a person who couldn’t seem to create a coherent life for himself. Why? He’d struggled in New York for all of six months before Warhol discovered him. He was a rock star, with managers, musicians, and producers at his beck and call, and I’m going to go out on a limb and say I bet that on an average night Reed had his choice of companionship, male or female. Even his friends looked a bit askance: “Lou was a real asshole — he was a prick — but I liked him,” said one of his producers.

He spent the rest of the decade veering about wildly, a platinum-haired glam-rocker one minute, an almost-Frankensteinian freak the next, a cuddly love man the one after that. Now, Reed was not as natural a star as some of those other names. He had a charisma but obviously an off-center one; his voice was capable of great power, but in much of his recorded work infrequently managed to meld with the song it was singing. At its worst, which was too much of the time, it ranged from a whiny bleat to an unattractive bellow. As for his talking voice — so gentle, so deadly in “Walk on the Wild Side” — it often came across as hectoring or pompous. No one would gainsay any artist’s right to follow a muse — look at Bowie’s ‘70s albums — but Reed just seemed erratic. So fans got a decadent song cycle here (Berlin) and an attitudinal collection of mediocre songs, indifferently recorded, there (Sally Can’t Dance); a two-record set of clanking noise and feedback here (Metal Machine Music), another tedious collection of songs, this one designed to show off “nice Lou,” there (Rock and Roll Heart). Two of his ‘70s releases had undeniable title tracks (Street Hassle and The Bells), but fans who looked for similarly compelling songs on their albums came away disappointed.

His successes were sometimes accidental. Dispensing with the kids in his first solo band, he accepted a new group of hard-rock musicians, who fashioned some hyperbolic chording as an intro to one of his best-known songs. The resulting track, leading off a 1974 live album called Rock n Roll Animal, made a new generation of hard-rock fans prick up their ears. This version of “Sweet Jane” became a rock radio classic and made the album a hit. He followed it up with a deliberately tossed-off work (Sally Can’t Dance, “the shittiest album I’ve ever made,” as Reed himself put it), and then the promisingly titled, entirely unlistenable Metal Machine Music, which was literally four sides of oscillating feedback loops. It was both a funny conceptual-art project and kind of a shitty thing to do to a hard-rock kid looking for another Rock n Roll Animal. In the last line of the liner notes, Reed rubbed it in: “My week beats your year.”

And yet he was capable of much more. In 1976 Reed finally delivered another consistent and moving album. It was produced by Godfrey Diamond, a disco producer. (He had been one of the creators of Andrea True’s “More More More”), with whom Reed eventually parted on bad terms. Coney Island Baby didn’t have a crummy cover, and there was an intimate, ghostly air in the production; Diamond coaxed out of Reed a vocal style for the album that let him half-talk, half-croon through the album’s tracks and recorded those vocals with a great deal of warmth. Song after song had a hook; deceptively lazy arrangements actually moved with a crack and a snap. He even conjures up a minor classic from Reed’s reflexive sarcasm in “A Gift.” (The chorus goes, “I’m just a gift to the women of the world.”)

The title song of Coney Island Baby is one of Reed’s most interesting works. It’s all built on a single strummed two-chord riff, here delivered almost absentmindedly, but with a relentless track of quiet lead guitar filigrees behind it. The song starts out as a sentimental high-school tale (“I wanted to play football for the coach”), but then widens its view to include a somewhat melodramatic gritty urban portrait (“Something like a circus or a sewer”), and refocuses back into something sincere (“The glory of love might see you through”). “Different people,” Reed tells us in a ferocious utterance, “have peculiar tastes.” Here again is Reed’s great subject: the roots of the deranged, the depraved, and the dysfunctional in our quote-unquote normalcy. He struggled to articulate this passion throughout his career, never more passionately and believably than here.

It’s worth mentioning at this point one of Reed’s ‘70s relationships, one with a somewhat mysterious person generally referred to in Reed biographies simply as “Rachel,” which is what she was called she was wearing women’s clothes. She went by Ricky when she was wearing men’s clothes. She was inseparable from Reed during this time, and it’s sometimes said the pair went through a wedding ceremony. Levy’s sources fill in and correct this picture. Her name was Richard Humphreys at birth; the supposed marriage was really a three-year-anniversary party, complete with a multi-tier cake to memorialize it. In 1977 the relationship foundered on Rachel’s desire for a sex-change operation, which Reed, as Levy tells it, was against. Rachel departed, and not even the street-level informants of Please Kill Me know what happened to her. Of the relationship, about all that is left, besides an old black-and-white photo of the pair cutting their cake, looking at all the world like newlyweds, is the end of “Coney Island Baby.”

The title of the song is taken from a keening doo-wop classic (by the Excellents) of no little drama and soaring harmonies. At the end of Reed’s “Coney Island Baby” comes something unexpected. A plangent swirl of that quiet guitar plays out against waves of whispers and dissonant harmonies. We hear Reed murmur, achingly — his most emotionally convincing moment on record — these words:

Sending this one out

To Lou and Rachel

And all the kids at PS 192

Man I swear I’d give the whole thing up for you

This is Reed at his best, a troubadour for all the Lous and Rachels, once kids too. Kids grow up; some become rock stars. Sounes’s contribution to the Rachel story is information from a friend of Reed’s who says that, some time after Rachel disappeared from Reed’s circle, he bumped into her on the street; she looked sick, he said, and told him she was living under the West Side Highway.

The ‘70s continue, chaos continues. Reed, often drunk onstage, had a penchant for provoking scenes at his shows. In 1979 he released The Bells, which has the distinction of being his second-least-commercial album, after Metal Machine Music. It’s a collection of nine songs, a lot of them some species of dissonant jazz, or boasting odd musical tropes, like Reed intoning the words, “Disco / Disco mystic,” over a groaning background, for nearly five minutes. At a show in New York, he halted proceedings from the stage to go into a tirade against Clive Davis, the head of his then-label, over what Reed thought was poor promotion for the record. Davis was in the audience.

The new boxed set — which has the unwieldy title Lou Reed: The RCA & Arista Album Collection — is as good a guide as you can want for this era. In a haphazard way he was a canny chronicler of his mythos — he released no fewer than five live albums in the 1970s. In his later career, repackagings came thick and fast, and you could be forgiven for rolling your eyes at the new one. But it’s said that he personally oversaw the remastering of the package before his death — 17 CDs in all. (Younger readers will want to know that “CDs,” or “compact discs,” were once the music industry’s vehicle of choice, before the technological advances that brought us the LP vinyl record.) It must be said that the albums he put the most effort into — Coney Island Baby and Street Hassle, particularly — sound devastatingly direct. The later stuff is more revealing as well, though this is a double-edged sword. The whole set, disappointingly monochromatic on the outside, is filled with goodies, including a nice coffee-table book, a large vintage poster, and a package of mini-posters, too.

The last 35 years of Reed’s life are more similar to that of a lot of his coevals: intermittent work intermittently hailed as a return to the artist’s best work, most of it quickly forgotten. It’s depressing to slog through even the remastered versions of his ‘80s releases — New Sensations, Legendary Hearts, Mistrial. Once in a while he would get a little MTV airplay with a novelty-esque number, like “My Red Joystick” or “The Original Wrapper.” But the vast majority of the work is by turns pompous and sentimental. He’d lost his ability to demonstrate things in his writing and so resorted to telling us about them. Sparked by inspiration to write a song about bottoming out, Reed then intones the words bottoming out, over and over again, the effect not helped by his scenery-chewing vocals. (Similarly bald sentiments include “I Remember You,” “I Believe in Love,” “Love Makes You Feel Ten Feet Tall,” “I Love Women,” etc., etc.) The song “Doin’ the Things That We Want To” is an insufferably chummy paean to Reed buddies like Sam Shepard and Martin Scorsese. It contains lines like this account of a Shepard play:

When they finished fighting, they exited the stage

Doin’ the things that they want to

I was firmly struck by the way they had behaved

(Here’s an example of where the remastering stuff doesn’t serve Reed well. The pristine intimacy of the sound just makes him sound even more pretentious.)

One aspect of many of even Reed’s classic-era albums that doesn’t get talked about enough is the sonic inconsistency. It’s a subtle thing, but most decent rock albums have a sonic palette that forms the core of the work. It’s not that every song must be orchestrated identically, but a good album will generally sound like it was recorded a certain way in a certain universe. Reed’s own lack of sophistication and the B-level producers he used over most of his career combined to make many of his records sound internally random, and jarring. And even fans can point to few nuanced compositions to make the search worthwhile. Along the way he sold “Walk on the Wild Side” for a TV commercial for the Honda’s short-lived line of scooters; Reed appeared at the end of it, to say, “Hey — don’t settle for walkin’!”

As the 1980s ended, Reed picked himself up and tried to create some big statements. New York was decently produced and got him a latter-day radio hit in “Dirty Blvd.” Critics oohed and aahed, but the plain fact is the scenes in “Dirty Blvd.,” and those throughout the album, were less than nuanced:

Outside it’s a bright night

there’s an opera at Lincoln Center

movie stars arrive by limousine

The klieg lights shoot up over the skyline of Manhattan

but the lights are out on the Mean Streets

Next came Magic and Loss, which was about capital-D Death, and the grandiosely titled Set the Twilight Reeling. The artlessness in both is pervasive. One song is a paean to Anderson, the performance artist. In it, Reed mixes clichés with lines that resist coherence and still manages to pat himself on the back for his own artistic daring:

You’re an adventurer

You sail across the oceans

You climb the Himalayas

Seeking truth and beauty as a natural state

You redefine the locus of your time in space — race!

As you move further from me, and though I understand the thinking

And have often done the same thing, I find parts of me gone

You’re an adventurer

Reed may have been intellectually insecure. He seemed to like references to literature, but more often than not these seemed gratuitous, like one song that has a verse devoted to random Shakespeare references. In another song, about the effects of chemotherapy, Reed sings, “It made me think of Leda and the Swan.” This English 101 allusion is left unexplained. (Was Zeus the radiation? Was the radiation raping the tumor?)

Reed toured, during this period, in a sullen, unfriendly fashion, sometimes sporting an unfortunate mullet, reading his lyrics, deliberately, from a music stand. After New York, he reunited with Cale for Songs for Drella, which the pair put together after the unexpected death of Andy Warhol. This, too, was almost stultifyingly literal and, leaving aside Cale’s spectacular instrumental work, musically moribund. (Parts of it sound like outtakes from Corky St. Clair’s musical in Waiting for Guffman.) Finally, in the early 1990s, the original Velvets reunited for a tour of Europe. It was a minor payday for the rest of the band — Tucker had been working at a Walmart in a small town in Georgia — but Reed refused to tour America.

The work from the last years of his life was bizarrely high concept. One was a two-disc interpretation of Poe’s The Raven; another was an album of atmospherics called Hudson River Wind Meditations. His last work was Lulu, a collaboration with Metallica based on German plays about a prostitute who comes to a bad end. Sounes says the recording sessions were contentious. The album is unlistenable.

Reed spent the rest of his life quietly with Anderson, whom he married in 2008. Aside from Lulu, his only aesthetic outrages were unintentional, such as when, appearing on Charlie Rose, he brought along his wife, who in turn brought along a motley lap dog. Rose pressed on in the face of this ridiculous tableau.

If in the end Reed’s tortured personality overwhelmed his art, some of what remains continues to resonate. His work from the 1960s and ‘70s in the 1960s was caught up by bands like R.E.M. and U2. His lifestyle in the 1970s isn’t quite the mainstream, but transexuality, gender reassignment, and bisexuality are now part of our social fabric. (Heroin, too, now that I think about it.) And then the songs: The towering guitar change-up on “Sweet Jane,” heroic nearly a half-century later; the filigreed melody of a song like “Femme Fatale”; the three-note riff, dropping off an emotional cliff, that undergirds “The Bells”; “Walk on the Wild Side,” an easy-listening stunner, arguably the most subversive hit single of all time.

A release I go back to again and again is Take No Prisoners, a 1978 two-disc live album. Smart, logorrheic, nasty, and oh so funny, it’s a journey into Lou Reed’s soul more entertaining and I think more revealing than any other of his records. His greatest songs fight for attention amid an accompanying stage patter that is part Lenny Bruce, part Mort Sahl, and part a certain current presidential candidate, another cranky New Yorker with issues:

[draws on cigarette] I have no attitude without a cigarette.

[pause] I’d rather have cancer than be a fag.

That wasn’t an anti-gay remark.

Coming from me, it was a compliment.

One highlight is Reed’s (very) long exegesis to “Walk on the Wild Side,” in which he mercilessly annotates further the characters in the song (“Little Joe was an idiot!”) and along the way tells the story of how it came to be written. He settles scores — dissing by name various New York rock critics. He riffs on music and spars with hecklers. He plays Lou Reed, and plays Lou Reed playing Lou Reed, creating a mirrored room of highly ironicized personality and anti-personality, stardom and image. And yet in the end it’s all really just the very picture of a wiseass boyman with insecurities and demons he would never tame, and all the more priceless for it.

And yet nothing can compare with the lovely, cathartic version of “Coney Island Baby” here. It’s a coursing workout with crushing dynamics and lyrical interludes. At the end, Reed drops the murmured dedication to Lou and the lost Rachel and replaces it with an extended coda. That coda consists of that single hopeful phrase, “The glory of love might see you through,” roared over and over, and over again. You can hear Reed babbling himself almost into incoherence. Blaring horns and some game backup singers wail, with almost Springsteenian grandeur, behind him. This closing maelstrom, his insistence that love can and must redeem us in the face of hate for the Other, goes on for minutes; let yourself get caught up in it and you believe it.

The music finally stops. “Sorry it took a while,” Reed snaps to the crowd. Clearly, he’d gotten off.