Secrets are difficult to keep until they’re forgotten entirely, and it strikes me that the revelation of the person (or people) behind the pen name Elena Ferrante was inevitable. What we’ll never know is whether Ferrante would have someday done it herself if it hadn’t (allegedly) been done for her by Claudio Gatti over the weekend, in Il Sole 24 Ore and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and on the blog of The New York Review of Books. Given its rarified reputation, that last one was an odd place for anglophone readers to learn that financial records and real-estate purchases point to Anita Raja as the author of Ferrante’s works, but no matter where the two-part article was published first we would have read about it in the newspapers, too, soon enough.

If Raja is Ferrante it’s not a surprise, at least not to me or to anyone who read an essay last year in Public Books that pointed to Raja, the signed translator in Italian of the East German novelist Christa Wolf, and quoted an Italian gossip blog: “Even the stones know that Elena Ferrante is Anita Raja.” Perhaps the only thing of literary value to be had from knowing that Raja is Ferrante would be greater scrutiny of the influence of Wolf on the fictions of Ferrante, which would have been a good question anyway.

As someone anonymous wrote, on the blog of the London Review of Books, the main effect of Gatti’s report is to ruin the fun — to raise all the wrong questions about richly imagined works of fiction in an age awash in gossip. Katherine Angel at Verso’s blog and Aaron Bady in the New Inquiry, echoing many voices on social media, have called the report misogynistic. It’s certainly hostile. That’s journalism for you. Gatti must have gotten the documents he relied on from a party or parties that should have been keeping them secret, and that’s who betrayed Ferrante. Gatti is just a reporter doing his job, as distasteful as that job sometimes is.

What strikes me as odd, and in spirit wrong, about Gatti’s report is the second part, an effort at crude biographical criticism in which he tells the story of Raja’s mother, Goldi, a Holocaust survivor, sourced to Elisabetta Mattioli, who co-authored a pair of German grammar books with Goldi. Gatti wonders about a link between her story and the “images of crisis” in Ferrante’s work, and implies that the mother’s story is the one Ferrante should have been telling all along. Perhaps someday she will — some fear she’ll never write again. (I doubt it.) Gatti’s not wrong that it’s a compelling story of survival, but it’s not the story Ferrante decided to tell in her novels. Deciding what stories to tell is what writers do, and if they need to keep a few secrets in order to tell them, we should let them. It’s no surprise when we don’t.

So now Ferrante will go from being a pen name to being the name of a reclusive author, unless she decides to embrace her celebrity — I don’t see her signing up to do a panel at the Brooklyn Book Fest next year, but who knows? And, as enticing as a literary whodunit seems to be to some readers, the silence or mystery that surrounds an author doesn’t necessarily enclose much of interest. In the case last year of Harper Lee, the only thing behind the silence was a woman close to death and an inferior manuscript that predated her masterpiece.

Sometimes shy people are just shy, and boring, and we all have the right to be boring, except on the page. I once asked a prominent literary biographer if he might next write his next book about Don DeLillo, knowing the two were acquainted. “No story there,” he said. “He sat at his desk and wrote.” (Brilliantly, I’m sure he’d add.) In general, literary biography is of limited literary utility. People with interesting minds sometimes lead interesting lives, but perhaps more often they don’t. (The ones who choose to live in retreat don’t always do it for interesting reasons, either.) And yet those choices do have an effect on readers, of course, some of whom are other writers. The spectacle of Norman Mailer had something to do with the hiding out of J.D. Salinger and Thomas Pynchon, both of whom became disgusted with the idea of literary celebrity, though the latter has occasionally used it as an opportunity for pranks. Late in life Mailer himself regretted the attention. “We wanted to change the nature of American life,” he told a French interviewer. “None of us ended up as heroes; we ended up as celebrities.”

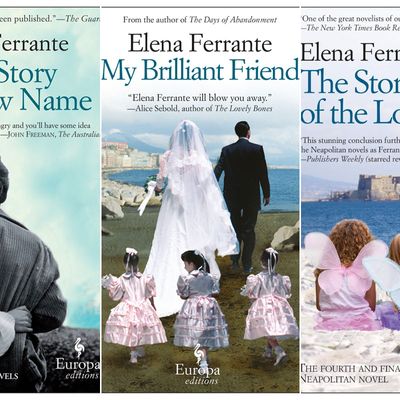

By comparison to Salinger and Pynchon, Ferrante, though unphotographed and pen-named, has been a promiscuous interview subject. Next month sees the publication in English of Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey, reportedly a self-portrait in fragments. I’ve no doubt it will be more of a pleasure than finding out that there are seven rooms in her Rome apartment.