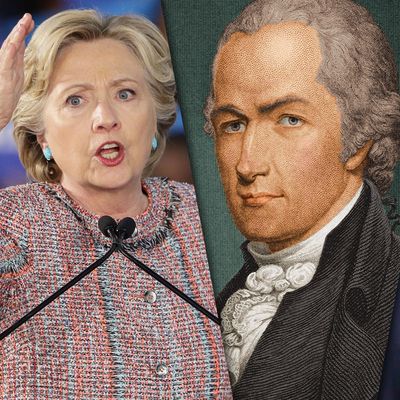

Vicious attack ads, smear campaigns, and salacious sex scandals. Sound familiar? According to the brains behind Hamilton, every old political tactic is new again. At the premiere of PBS’s Great Performances: Hamilton’s America at the United Palace Theatre, the documentary’s director Alex Horwitz, Alexander Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow, and Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda unanimously agreed: Alexander Hamilton wouldn’t be surprised by the overall madness playing out in the 2016 election. After all, Hamilton witnessed scathing political attacks and deadly duels firsthand.

In fact, during the election of 1800, a group of Federalists — Hamilton’s political party — published false obituaries proclaiming Thomas Jefferson’s death in an attempt to defeat him in the election against John Adams (Jefferson won). “That’s ugly politics at its worst, so the more things change, the more they stay the same,” Horwitz said.

If you think that the media is biased nowadays, just consider what newspapers were printing in the 1800s. Democratic-Republicans James Madison and Thomas Jefferson founded The National Gazette to communicate their belief in states’ rights, while the Federalist newspaper, The Gazette of the United States, shared views supporting a powerful central government and weak states. Hamilton, meanwhile, jumped into the media game in 1801 by founding the New York Evening Post (now the New York Post). Political foes Jefferson and Hamilton were constantly dueling each other via the press — Jefferson’s surrogates frequently attacked Hamilton, who responded by penning anonymous essays. This sparring, Miranda noted, was downright vicious, frequent, and relentless. “They talked smack about each other all the time,” he said. “That part of the process is not new.”

While Hamilton was uncompromising and a purist at heart, Chernow said that ultimately, when pressed, he was able to set aside chilly Jeffersonian relations for the good of the country. (The same probably could not be said of Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, who has sparked outrage over his refusal to say if he’ll accept the legitimacy of November’s election results.)

For example, when the presidential race between Jefferson and Aaron Burr resulted in a tie in 1800, the Federalist-heavy (and anti-Jefferson) House of Representatives had to break the tie. Trash talk aside, the secretary of Treasury had to make a decision: Should he support Jefferson or Burr, neither of whom he particularly admired? Chernow explained the logic. “Hamilton decided that he would rather have his political enemy Jefferson than his nemesis Burr for the simple reason, as he said, that Jefferson had the wrong morals. Burr had no morals at all.” So Hamilton put pen to paper and urged the House to vote for Jefferson. And just like that, Jefferson was elected president.

While some Americans may say they’re choosing between the lesser of two evils on November 8 instead of wholeheartedly casting a ballot for one candidate over another, Chernow pointed out that Hamilton’s letters supporting Jefferson essentially argued the same thing. “[They’re] also a very, very strong warning of how destructive things can get when we slide off into extreme malice and partisanship,” Chernow said.

There is, of course, one key difference between politics then and now: The existence of social media and the internet has drastically changed how candidates communicate their messages. “The speed at which a Donald Trump tweet can change the makeup of what’s discussed that day” is astounding, Miranda said. “I think his head would spin at that.”