Where does this leave art? That’s like asking “Where does this leave love?” While we sometimes break faith with it, art never breaks faith with us. It’s always there. Especially when we need it. The election left many feeling alienated, alone, in shapeless psychic pain. But in fact this foul, broken, alien place is a very old locus of art. Recently, art has been this high-powered-success-machine mainstream sensation; artists have become celebrities; we’ve been treated to narcissistic pictures of pretty people at glamorous events wearing $2,000 worth of clothes. Outside the world of fine art, too, pop culture swallowed all of culture, and the entire cultural apparatus seemed to reorient itself to orbit the White House. One of the strangest features of the past eight years, which many of us on the left might not have even recognized as strange, was that our biggest pop star and our reigning rapper emeritus were actually friends with the president and First Lady.

I love Beyoncé, but it is not often that great artists do their great work while living so close to the glow of political power. For most of art’s long history, artists have lived on the edge of the village — poor, neglected, commiserating with one another, optical shamans transforming the world in mythic, mysterious, complicated, crazy, renegade ways, processing catastrophes through unexpected lenses, giving comfort, wisdom, relief, wonder, linking us with humanity, emotions, intellectuality, even the infinite. Alienation is the wellspring of art; in fact, feeling alone is often why you become an artist. Which means that, in times of artistic alienation, distress is often repaid to us in the form of great work, much of it galvanizing or clarifying or (believe it or not) empowering. That is because art isn’t a superfluous, elitist escape; it’s a way of knowing the world, a place to find common cause and not fall apart. Adorno said, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” Yet the very phrase is poetic.

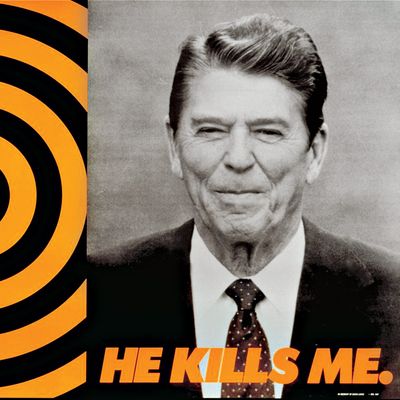

They may not know it yet, but Trump’s victory is a crucible of possibility for a new generation, who will do what artists have always done in times like these: go back to work. Sometimes the masterpieces come instantaneously after trauma, as with Picasso’s Guernica or Goya’s Disasters of War. More often there’s a lag between events and art. In the late 1940s, Abstract Expressionists finally transformed the pain and horror of the Depression and World War II into existentially devastating painting. The irony of these lags is that a cool decade like the 1950s produced an art as emotionally hot as AbEx while the hot culture of the 1960s enshrined the cool art of Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Pop, and Minimalism. More recently, the group mind responded to the AIDS crisis of the Reagan era with one of the greatest collective works of folk art ever made: the AIDS Memorial Quilt. Which is actually a good case study in what gives oppositional art its charge: It gains in power by being more than the sum of its subject matter.

And then there is pop culture. Here one does not have to remember that far back. Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain arrived only a year after anti-gay-marriage ballot initiatives helped propel George W. Bush to reelection. The Reagan ’80s didn’t just bring us that AIDS quilt (and Basquiat) but the entirely new genre (and form of political protest) of hip-hop. Vietnam gave us Apocalypse Now.

How will this play out, this time, in the art world? Even if many remain in their own bubbles or keep posting pictures of food and stay immersed in the culture of celebrity and complacency, this is all a kind of call to action that will yield things not yet fathomed or decanted. Georges Bataille wrote of “creation by means of loss.” I can imagine the typical arty gestures of spareness art giving way to another kind of organization, marked by extremes of gesture, things more homemade, unpredictable, vulnerable, bizarre. Maybe artists will work with mechanics to disable deportation buses at night. Maybe there will be a move away from so many artists and curators making deconstructivist institutional-critique art, which is ultimately a way for insiders to pretend to be outsiders — and which already feels like folly in a time when politicians have declared that institutions will be defunded and dismantled. Some fear the collapse of the art market, but given the wealth of art patrons, I doubt that will come to pass. More important, the shift or clusterfuck under way may jar professionalized artists from being part and parcel of the career machine and return them and all of us to our rightful outsider gypsy position — aristocratic bohemians with highly calibrated bullshit detectors. After all, why should art want to serve consensus? What is interesting, or exciting, or urgent about consensus?

*This article appears in the November 14, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.