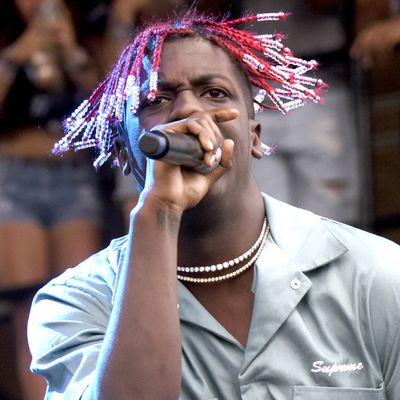

When I met Lil Yachty a year and a half ago, he was a cherry-braided outcast creating a path to fame where one didn’t really seem to exist. The handful of tracks on his SoundCloud page mixed kiddie cartoon and video-game ephemera with happy-go-lucky hooks. “I Got the Baag” sampled the Migos’ “Hannah Montana” and Super Mario Bros. 3. “All Times” was an iced out remix of the theme to Nickelodeon’s Rugrats. Yachty seemed meek but driven, determined to infiltrate the charts with his patented “bubblegum trap music” — all gooey synths, pillow-y low end, tender melodies, and lighthearted subject matter — and smartly introduced himself to all the people up and down the Eastern seaboard who would be instrumental in making it happen. He arrived on the New York hip-hop media circuit fresh-faced but already very popular; his label boss and family friend Coach K, of the Atlanta Trap powerhouse Quality Control, pridefully noted that the kid had been pulling in half a million SoundCloud plays a day just off loosies. But in order to advance, Yachty would have to meet the hip-hop peanut gallery.

Yachty played the first move perfectly: His debut full-length mixtape Lil Boat scaled back the big unclearable samples and focused on trippy synths and teen urges expressed through unfussy, unpolished raps and falsetto-heavy choruses. It felt rare and pure. Boat was a beam of joy that owed as much to the music of Sesame Street as anything running concurrently in or around Atlanta. All of this made Yachty the perfect battleground for hip-hop purists grumbling since time immemorial about rappers whose craft isn’t up to snuff.

Older rap diehards have been at ideological loggerheads with hip-hop’s current under-25 set for the last five years. The rallying cry was the 2012 arrival of Chicago’s Chief Keef, a bleak trap rapper who, at just 17-years-old, was branded as a herald of rap’s unruly future because his music vividly projected the harsh physicality of inner-city violence in the plainest terms, when many felt what was needed is someone who could speak eloquently against it. His Finally Rich album was a source of outrage from rap fans who felt like artists, labels, and blogs supporting it were hyping “ignorant” music and capitalizing on young black death. The rift never closed, even when Interscope dropped Keef after Finally Rich lost chart footing, and his legal troubles began to mount. The offended parties just found new records to wage war over.

Wiz Khalifa coined the term “mumble rap” in an interview at Hot 97 that touched on up-and-coming rappers who “don’t wanna rap.” It quickly became a catchall put-down for any youth rap that dared to flout ’90s rap conventions for diction and delivery (even though those same ’90s purists championed groups like Das EFX, who played fast and loose with proper English). Not even the Migos, whose delivery is breakneck but never muddled, could escape the charge. It’s a bad term for music for several reasons, the main one being the audacity to create a whole subgenre out of music you admittedly refuse to listen to closely. Rap is an art form that rewards examination and repeat plays. Yachty’s music was deemed unworthy of the luxury.

Critics winced at Lil Boat. Hip-hop personalities like Hot 97 host Ebro groused about bars. A messy freestyle from a radio appearance got memed around the net as one of the station’s worst ever. Yachty let slip that he doesn’t listen to 2Pac or the Notorious B.I.G. in a talk with Billboard. They put it in the headline. Pitchfork got him to say Biggie was “overrated.” (Boat, in fairness, was born in late 1997 and never saw a day that either rap legend drew air. In a perfect world, we wouldn’t grill teens about figures that never seemed alive to them.)

Controversy can easily outstrip craft for a young rap artist without a lot of points on the board. At radio, you run into guys like Ebro, who adhere to a strict, old-world view of hip-hop — one that’s confounded even by Rae Sremmurd and the Migos — and habitually nudge kids with no media training into damaging statements about music outside their purview. Footage floods blogs hungry for the latest scandal, and suddenly a positive, informative 30-minute interview is reduced to its 15 weirdest seconds, and artists trying to push their music to new audiences are closed off from them forever. The road to rap fans’ outrage is slick, and the press that serves them knows what buttons to push to get it flowing. They hype strife between artists and on-air personalities and then schedule tense follow-up interviews, just like WWE pay-per-view promos.

In the press and on social media, Yachty had quickly become someone rap fans felt should be checked or curtailed rather than celebrated, and he began to use his music to respond. Last July’s Summer Songs 2 opened with the Ebro diss track “For Hot 97” and passed through angry cuts like “Why?,” “Shoot Out the Roof,” and “Up Next 3,” where Yachty appeared to vent about his bad press. Aggression made Summer Songs 2 a rockier ride than Lil Boat and set the scene for Lil Yachty’s formal debut studio album Teenage Emotions, a fascinating sorta-misfire that swears it has nothing to prove but attempts so much in 21 tracks that the assertion can’t possibly be true.

Teenage Emotions’ biggest mistake is thinking that, as the Album, it needed to behave differently than Yachty’s mixtapes did. There’s a three-track stretch in the middle that whizzes from reggae (“Better”) to Diplo-sponsored EDM (“Forever Young”) to talkbox-infused throwback R&B (“Lady in Yellow”). The lead single “Bring It Back” is a synth-pop ballad. “No More” tries its hand at the fuzzed-out robot soul of Kanye West’s 808s & Heartbreak. The range is admirable, but Boat is still learning how to use his instrument, and a few of these genre excursions come out looking like simple pastiche.

The songs that run on the mixtapes’ winning bubblegum Trap formula are a grab bag. “Priorities” is a funny “fuck school” anthem with a simple, memorable chorus (“My priorities are fucked!”). “Peek a Boo” and “Harley” grate with hooks that borrow the Migos’ repeat-the-song-title trick but manage none of the magic. “Say My Name,” “DN Freestyle,” “Dirty Mouth,” “X-Men,” and “All You Had to Say” pepper the album with ample words for haters, even after “Dirty Mouth” swears that Yachty’s enemies don’t bother him. (There’s only so many times you can promise to bed your critics’ moms and aunts out of spite before you start to come out looking pressed.) They’re not all bad songs, but they do create frustrating pockets of rage throughout an album from an artist who promised something different from aggro chest-beating, whose strength is good-natured fun.

The anger directed at Lil Yachty over the last year has taken poisonous root in his art. Teenage Emotions bristles when it should bubble, like the Migos mixtape No Labels II, where the young Atlanta group sent shots at critics and imitators when they could’ve been sending up more kooky comedy trap like “Birds” and “Contraband.” It only worked for the Migos because their music had a refined sound and scope that left room for rage, and because they sold their tightly wound round-robin raps well. Yachty’s thing is unbridled happiness and weightless hooks, and Teenage Emotions could’ve used a bit more of both.