Marie Cosindas was barely four-foot-eleven up on her tiptoes, if that. She may have weighed 100 pounds as long as she was lugging her big old Linhof wooden-box portrait camera and her tripod and stacks of four-by-five-inch film slides around in her duffel bag. She was so soft-spoken that if you were eating a potato chip or even a Stoned Wheat Thin, you couldn’t make out a word she said. And inside all that delicate wrapping was an iron rod.

She had started out as a painter in the Late Impressionist style … with next-to-no success. When she was 36 years old, she decided to switch to photography and was determined to learn it from the best there was. She applied to the famous photographer Ansel Adams’s Creative Photography Workshop in Yosemite, California, and he turned her down. She took that the Marie Cosindas way. She rang Adams up on the telephone and demanded, in her little ladylike voice, that he admit her. When he declined, she ladyliked him with incessant phone calls and letters from Boston until he caved in and became her mentor in his studio on the other side of the country. Thanks to Ansel Adams’s pull, she became one of 12 photographers chosen by Dr. Edwin Land to experiment with his new invention, Polaroid color photography. She was the one who turned it into an artistic medium unlike any other. When she died last month, at the age of 93, she was one of America’s leading art photographers — or was it leading classical painters? You could choose either one, or both, and not be wrong.

Her first job, in her teens, was painting hand puppets and suchlike for a toy manufacturer in Boston. He directed her, in effect peremptorily ordered her, to change the way she did the puppets’ faces. She did one puppet his way, studied it for about 15 seconds, and told him, “I’m leaving,” not in a testy, put-out tone but as if she were passing along a bit of information concerning the company’s employment prospects. Then she turned around and walked out.

She was the eighth of ten children born to Greek immigrants living in Boston’s South End when it was a reeking slum full of tenements, recent immigrants, poor black folks, poor white folks, and crime. All 12 of the Cosindas family lived in two rooms. Her father was a carpenter and sometime furniture maker. Her mother had so many children, she didn’t know what to do. She never did learn English, and so they all spoke Greek at home. Nonetheless, apparently it was the mother’s influence that created an extraordinary blossoming of classical talent among her children. Marie’s brother Frank was a concert pianist, and her brother Nicholas was an opera singer, but neither became as famous as their younger sister Marie.

Growing up, she had a corner of one of the two rooms to herself and became a dedicated collector of small objects she would use to create assemblages. She suffered terribly from dyslexia but didn’t let it hold her back from studying design at Boston’s Modern School of Fashion Design during the day and painting at the Boston Museum school at night. For 16 years, from 1944 when she was 19 to 1960 when she was 36, she made a living as a textile designer while working constantly at her passion, which was painting.

In 1959, when she was 35, she visited the old family homeland and photographed Greek landscapes for “scrap,” pictures to use as reference material for paintings. They turned out so well, she became fascinated by photography’s possibilities. That was when she demanded, in her way, that Ansel Adams become her instructor.

Like all the famous art photographers at that time, the early 1960s, Adams photographed only in black and white. Color photography did not capture true colors and was considered fit only for magazines, advertisements, and comic strips. Adams admired Marie Cosindas’s talent but said she was shooting in black and white and thinking in color. As Adams recounted in an interview: “Everything she’d try to do would be a color composition. She’d ask me to look in the camera, and I’d say, ‘Marie, that’s a nice thing, but it’s really in color. You can’t separate these values in black and white. You’re thinking in color.’ She found that she was thinking in color,” Adams continued, “and worked very seriously, then got in with Polaroid to a most extraordinary degree. She made one of the great contributions.”

She “got in with Polaroid” because Adams led her straight to Dr. Edwin Land, the inventor of Polaroid photography, then known as Polacolor. Dr. Land was looking for photographers to experiment with the novel process, and Marie Cosindas was one of 12 he chose. She turned out to be the only one who got it, i.e., how to turn Polaroid into a new art medium. Conventional color film came out in the form of a highly concentrated field of microscopic dots. If you enlarged the picture, you soon ran into the risk of separating the dots from one another just enough to ruin the image. Dr. Land’s Polacolor came out smooth as paint no matter what the size. Ansel Adams said, “Marie Cosindas uses the Polaroid color, which is a very beautiful smooth color [with] more ‘pigment’ value than otherwise. She’s achieved some perfectly beautiful effects … and will use mixtures of tungsten and daylight, will actually arrange and compose in color.”

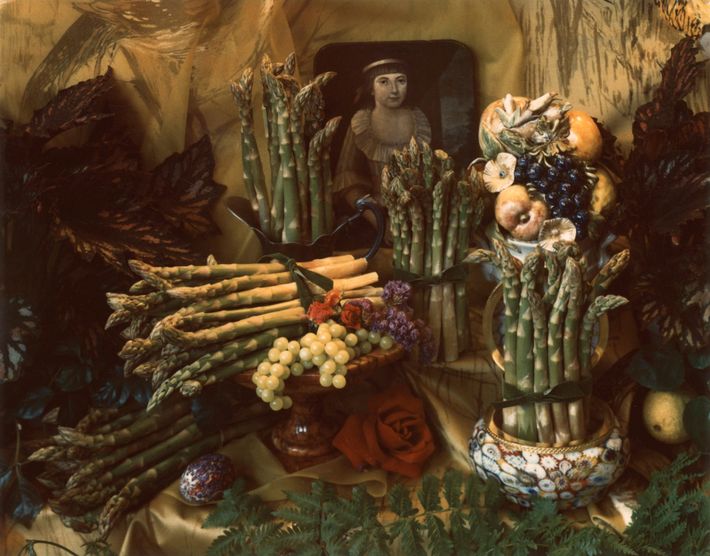

Marie Cosindas shot the classical subjects: still lifes, assemblages of everything from masques of human faces to stalks of asparagus in highly formal arrangements, and portraits in the style of the old masters, all in Polaroid. She tried experiments nobody had ever even remotely thought of. She warmed up exposed film in rooms heated up to 90 degrees. It made skin tones fuller and richer. She Scotch-taped double color filters, typically orange and yellow or magenta over the lens. She pushed exposure times to give portraits almost completely dark backgrounds with the subjects emerging in the center but never completely, à la Rembrandt. She was painting with film. She started off doing pictures at four-by-five inches. Eventually she made pictures the size of a wall, eight-by-ten feet. She made the first photographs of human beings at their full size, to the very inch, without sacrificing any of the depth and painterly richness of Polacolor.

A Saturday Review interviewer said to Ansel Adams, “It indicates she made some kind of great breakthrough at [your] workshop.”

“Well, that was her own breakthrough,” said Adams. “In other words, she decided that she was seeing in color. Now, she’s a photographer that works entirely by intuition. She has very small technical knowledge. I don’t say this critically, but by trial and error she determined the use of various filters and developing times. She doesn’t know how to use a meter. She’ll make her first picture, but perhaps finds she needs a little more exposure. Finally, she gets the quality she wants. But, of course, she’ll go through $30 worth of film to get that good print!”

The Museum of Modern Art’s curator of photography, John Szarkowski, was bowled over by the new medium and the new artist as soon as Ansel Adams and Dr. Land called her to his attention. Bowled over! is the expression. Barely a year later, in 1966, Szarkowski gave Marie Cosindas the first one-person show of her new career … at the Museum of Modern Art. A solo show at the museum was the top honor an American modern artist could realistically hope for, the painter’s equivalent of a Pulitzer Prize, and here was Marie Cosindas: the tops just four years after her first training as a photographer. No American artist, none, had ever ascended so fast.

That was the start of a Marie Cosindas boom, an explosion of publicity and praise and exhibitions all over the country. On the heels of the Museum of Modern Art, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts gave her a big exhibition the same year. Big solo exhibition after big solo exhibition … the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Art Institute of Chicago, the International Center of Photography in New York … grant after grant, including a Guggenheim and a Rockefeller … honor after honor, among them honorary degrees from the Art Institute of Boston and Philadelphia’s Moore College of Art. To top it all off, in 1978 Szarkowski would put her in a pantheon of the greatest artist-photographers in the world, a sensational show called Mirrors and Windows at the Museum of Modern Art.

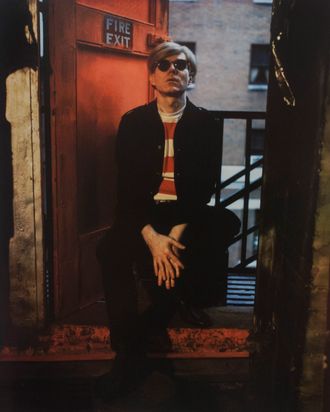

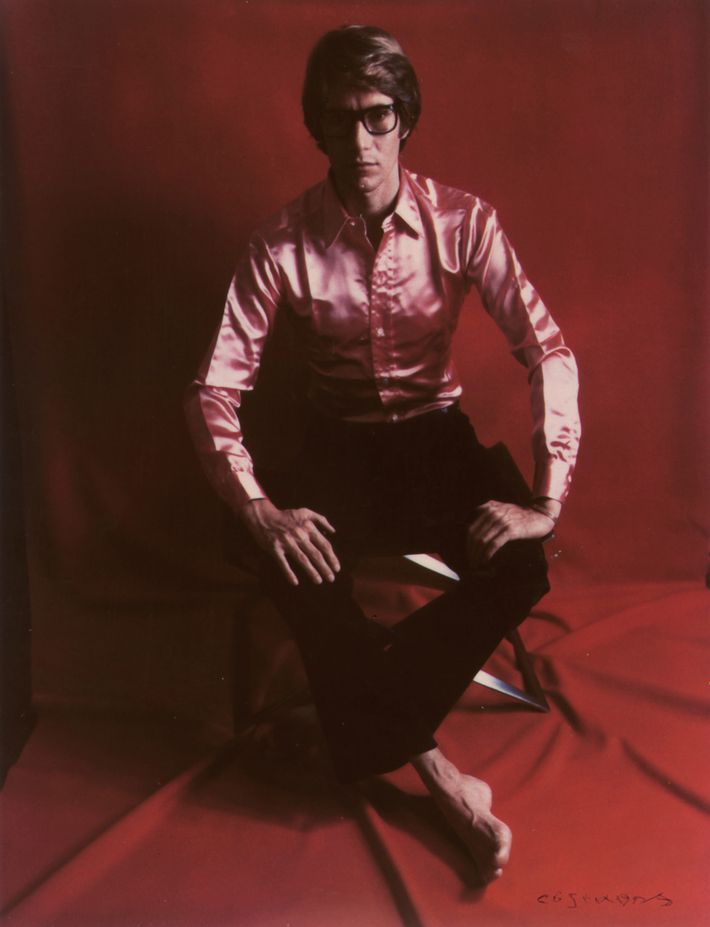

Celebrities couldn’t get, or get put, before her camera fast enough. It was practically a melee … Truman Capote, Faye Dunaway, Audrey Hepburn, Robert Redford, Paul Newman, Andy Warhol, Coco Chanel, Madame Gris, Yves Saint Laurent, Ezra Pound … waves of articles from 1963 to 1969 in every imaginable sort of magazine from Popular Photography and Foto-Magazin Munchen to Life (twice), Esquire (four times), Redbook, House Beautiful, Ladies’ Home Journal … lectures (who cared anymore about the hardly there voice?) at Harvard (twice), Brown, even the University of Nebraska.

One day in 1967 (as I mentioned in the introduction to Marie Cosindas: Color Photographs) she arrived at my apartment in New York to photograph me for a series called “The Dandies.” (Others were Andy Warhol, Richard Merkin, Will Davenport, and Sven Lambert.) Ah, well … in 1967, I’m afraid, I used to sit still to be photographed for any purpose whatsoever … as long as it did not involve removing my necktie and collar button … or my vest … or gold pocket watch and chain … or wearing a funny hat or in any other way appearing informal, casual, affable, or fun-loving. Marie Cosindas had been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art the year before. So I put on a new suit, beautifully tailored. I was particularly proud of that suit. It had a navy-blue jacket with buttons covered in the same light-gray unfinished worsted the double-breasted vest and pleated pants were made of. I remember wondering if any man in this century, the 20th, had ever looked spiffier.

The doorbell rang. Before I answered it, I fixed a confident, slightly smiling, amusingly knowing look on my face. I opened the door, and here was a diminutive woman with wavy brown hair and a voice that soaked up her words like absorbent cotton. She was carrying a duffel bag almost as big as she was. It contained her equipment, which included no light stanchions — she worked only in natural light — and no silver umbrellas. Then all at once, in the softest of voices she directed me to go change my clothes and to come back in a white suit, white shirt, a blue necktie, blue socks, and blue pocket handkerchief. Now, this is what I mean about her invisible microwave willpower. I can’t explain it, but any possible protest seemed hopeless. I went off and changed. She said very little as she set up an ancient-looking tripod and put an equally ancient-looking camera and black hood atop it. Then she had me push a big round, orange-upholstered tub chair directly in front of and less than an inch away from the canvas of an orange, blue, and magenta painting that went from floor to ceiling and told me to sit down just so … with my face close to the canvas. Then she bent down and disappeared under the hood. In that stance she looked about three feet tall. The camera used not rolls of film but individual film plates. After each click of the camera, she would come out from beneath the hood … remove the plate, separate the film’s two surfaces causing a brown goo to seep out around the edges. She would study the results for minutes … minutes … minutes … minutes … saying nothing … put in another plate and disappear under the hood, repeating the cycle over … and … over … and … over again. She never showed me a picture and she never spoke. Over … and over and … over again … she kept it up until I could feel my Mr. Wonderful expression draining from my face. Soon I had no idea what I looked like. It wasn’t until months later that I saw a print of the photograph and realized she had put my mouth so close to an orange blip the shape of a comic strip speech balloon, I appeared to be talking in orange. The rest of my face was in such deep shadow, it was virtually invisible.

When the cosmetics queen Helena Rubinstein commissioned her to do portraits of fashionable women for an advertising campaign, Marie Cosindas got her first close look at the world of fashion — and began treating herself to clothes by Schiaparelli, Christian Dior, and Chanel. She was the best-dressed female photographer in America, but she was so tiny, nobody noticed. Everybody did notice, however, when she began demanding of the Rubinstein people, Cosindas-style — and getting — chauffeured limousines to take her to and from the shoots or wherever else she wanted to go.

Among friends she got down off that new high horse and uplifted her voice and her joie de vivre and entertained them with stories of her experiences with all the famous nobs. And they couldn’t have enjoyed it more. They besieged her company. She lived alone, but she was seldom alone during her waking hours. She was highly popular, in no small part thanks to her generosity and the sweet concern she showed everybody she knew. She and Ansel Adams and Dr. Land became the best of lifelong friends.

Movie companies began to commission her to do Polaroid portraits for promotion: The Great Gatsby, The Sting’s Robert Redford and Paul Newman. As her income accumulated, she began to invest in stocks and bonds — on her own, no broker, no adviser — and made spectacular profits. “To Fortune, a much-aligned lady!” as Evelyn Waugh once put it — because she developed a spine-bending scoliosis in the early 1980s and suffered several serious falls. She went through a series of operations. Back surgery seldom leads to complete recovery. She could no longer handle equipment or travel easily. For 25 years she did very little photography, and her fame began to fade. When the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth mounted a major retrospective in 2013, it was a return from oblivion. She was 89 years old.

Two months ago, April 16, she gave a lecture and workshop at Fitchburg State University in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. One of her old friends, Ansel Adams’s daughter-in-law, Jeanne Adams, was on hand. She was impressed by Marie’s energy and strong presentations. They had dinner afterward and laughed and reminisced. Jeanne had never seen Marie happier or in higher spirits.

That turned out to be her happy ending. Two weeks later she came down with a severe head cold that quickly turned into pneumonia. She entered Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. For two days she rallied and seemed to be coming out of it but relapsed and died on May 25.

Since time was, there had been only three forms of art available to an artist: drawing, painting, and sculpture. Marie Cosindas had created a fourth: Polaroid color. It could have been genes that made her a tiny woman. But only genius — plus a willpower of iron — could have made her a tiny giant.