It was Labor Day weekend, 2008, and RuPaul had escaped the heat in a friend’s Hollywood Hills pool, taking in the expansive views of Los Angeles before him. Production on the first season of RuPaul’s Drag Race would kick off the next day, and in his usual introspective way, the drag superstar was thinking about the future. “I remember being in that water on such a hot day thinking, from this moment on, my life will be very different,” he recalled. “And it absolutely has been since that day.”

RuPaul, who became the world’s biggest drag star in the ’90s with the release of his single, “Supermodel (You Better Work),” had been away from the limelight for about a decade when Logo picked up his show. But he sensed his third act might be his biggest. President Obama was about to be elected, and a new social and cultural order was in the air, the kind that made it possible to imagine drag thriving beyond underground culture. “I knew the show’s mission statement was to celebrate the art of drag,” RuPaul said, explaining his early optimism about the show’s appeal last month, four days before production on the show’s tenth season began in Los Angeles. “And I knew that drag has more significant meaning and power than just what it seems like on the surface — it speaks to the duality of our lives as humans on this planet.”

As it has turned out, he wasn’t fantasizing. Since Drag Race premiered in 2009, 11 seasons have aired, including two All-Star editions (a third was just picked up). The competition show with a car-race motif spawned three spinoffs, UnTucked, RuPaul’s Drag U, and RuPaul’s Drag Race: Ruvealed, and led to the creation of RuPaul’s DragCon, which has catapulted many of the show’s 113 contestants to international stardom. Last season, Drag Race made the switch to Logo’s sister network VH1, where its ratings doubled and popularity soared higher, jump-started by a Lady Gaga appearance in the premiere that clocked nearly 1 million viewers. In May, Saturday Night Live spoofed the cultural juggernaut during its most popular season in years, with a skit featuring Chris Pine and four other cast members as straight car mechanics who love Drag Race and engage in a lip-sync battle. Then came the kind of acceptance that RuPaul never anticipated, or even particularly desired: In July of this year, the series was nominated for a whopping eight Emmys, including outstanding reality competition. RuPaul also was nominated again for his work as host (he won the trophy last year), a job with several roles: tough taskmaster, therapist, runway slayer, judge.

But long before it gained mainstream acknowledgment, Drag Race had a devoted audience around the world, who knew there was something unusually real here from the start. “I think about the young people out there in Saudi Arabia and Asia and South America and Wyoming, who have watched the show and have found refuge here with our girls and our vernacular and our outlook on life,” RuPaul said, reflecting on the show’s contributions. “I feel that the legacy of our show, Drag Race, is in those young people, and they will carry that legacy with them for the rest of their lives.”

The road to Drag Race was paved 32 years ago at a music seminar in Manhattan, when 24-year-old RuPaul met Randy Barbato and Fenton Bailey, the founders of World of Wonder Productions, who would become his managers and best friends. At the time, Barbato and Bailey were in a band called the Fabulous Pop Tarts and primarily managed music; RuPaul, meanwhile, was trying to sell his first record. “We came from the same background,” RuPaul recalled. “We were all devotees of the church of Warhol. I had grown up reading Interview magazine and thinking my path was to move to New York, become a Warhol superstar, create a persona, and move to Hollywood. When Randy looked at me that day, I could see that he saw what I saw.” Barbato says he recognized RuPaul’s star quality immediately. “It’s the same thing he has right now,” Barbato says, “but back then it was hard for a lot of people to get beyond the wig and the heels.”

World of Wonder took on RuPaul as a client and hired him for Manhattan Cable, a TV magazine show that combined public-access cable clips with interviews, and later produced other shows with him in the U.K. Barbato started conversations with RuPaul about a reality show in 2004, around the time he and his frequent collaborator, Michelle Visage, began co-hosting a morning radio show in New York. Having just released Starrbooty, the fourth installment in his secret agent–supermodel series, RuPaul was ready to return to show business, but he resisted the idea of a reality competition show because he believed the genre was mean-spirited. When Tom Campbell, a development executive who had worked at MTV, Warner Bros. Television, New Line Television, and ABC, joined World of Wonder two years later as head of development, he broached the subject with the drag star again. “I wasn’t interested in doing anything that was going to cast drag in a negative light or ridicule it, but the winds of change changed my mind,” RuPaul said. “The Obama movement was happening, and I could feel it in my bones that it was time.”

Campbell, who’s now World of Wonder’s chief creative officer, came up with the show’s format and its titular pun, while the producers and RuPaul came up with challenges, based on obstacles the drag star faced early in his career. “Tom understood my voice and I knew he could write for my voice,” RuPaul says, “and I knew that I could really be myself with Randy and Fenton because they are my tribe. I knew they would look out for me.” World of Wonder, which produces other non-scripted fare such as Million Dollar Listings and Wishful Drinking, envisioned the show debuting on Bravo or E!, but both networks turned it down. “They heard the pitch, which was a very good pitch, and everyone really loved Ru, but they were like [whispers] we can’t do drag. You know we can’t do drag. You get it. And it was like, really?” Campbell said. “We had different expectations, but Logo ended up being the perfect place for the show. We’ve been its biggest hit for as long as it’s been on the air, and they’ve let us make the show we want to make.”

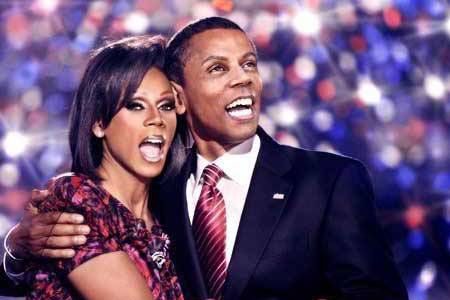

The first season was shot while President George W. Bush was in office, but aired right after Obama’s inauguration, which gave Drag Race its first viral hit: the introduction of the Rubama promo, featuring him as both President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama.

“We enjoyed and paralleled the Obama years and the opening up of our nation and of our government and inclusiveness and Drag Race hand in hand — no coincidence,” Campbell said. “And we shot this last season, season nine, when Obama was in office. We were hoping Hillary would be next, and then we realized it was gonna be Trump. And our rallying cry was, ‘RuPaul’s Drag Race now more than ever.’ People were hungry for it because the reality show in Washington is so upsetting.”

Bailey thinks the current political movement is actually benefiting the show, and drag in general. “At the time we were starting out, it was just a general aura of conservatism, but now it’s something different,” he said. “The whole point about drag is it doesn’t ask anyone’s permission. Drag and resistance go hand in hand.”

The show’s queens attract a lot of attention with their creativity, talent, and boldness, but Drag Race also stands out as the only show on TV that consistently features gay people from different ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic backgrounds. “The show has always offered hope about the human race,” Barbato said. “It inspires the people who watch it. During these dark times, it is not only inspiring that die-hard fan base, but I think it has also inspired the industry a little bit. It might be part of why people might be more motivated to include us and invite us to the big kid’s table.”

Before RuPaul was nominated for the Emmy he won last year, he famously told Vulture in an interview he’d “rather get an enema than an Emmy.” He’d done fine without mainstream acceptance up until that point, and didn’t need it for validation. “The truth is I’ve never done this for recognition; I do this because I love it,” RuPaul said last month, reflecting on the show’s eight nominations. “But my whole career has been on the fringe. Politically now, it feels like our collective narrative has been abandoned, like we’re moving away from the openheartedness that we felt in the previous eight years. Don’t get me wrong: I feel our show always deserved all of this, but maybe what you’re seeing now is that Hollywood is picking up the slack since the country is going backwards.”

Making political statements is not the show’s mission, though the producers know the nature of drag and its unwillingness to conform cannot be excised from the political conversation. “We don’t have an agenda,” Barbato said. “We are not particularly political. We are all big, loud gays; we always have been. But what makes us the happiest of anything about the nominations is to be making a show that recognizes actual artists and gives them a platform. And not just the queens who are on our show, by the way — people are now interested in drag in general.”

The show’s Emmys recognition drives home even louder what first-season winner BeBe Zahara Benet says she tried to convey in her season: “It gives us an opportunity to celebrate ourselves, and it tells little boys like me that you can make a career out of this. You can be a drag performer. Dressing up like a woman does not make me less of a man.”

From its first season, the success of Drag Race has lived on how expertly it weaves entertainment, comedy, and emotional truth to tell the story of personal transformation. What other reality show contestants have to sew their own costumes, do their own makeup and hair, tuck their you-know-whats, write songs or scripts, choreograph routines, and prepare a lip sync in less than a day? And nowhere else in the TV universe is there a reality host doling out wisdom, and messages of acceptance and tough love like on Drag Race.

“All of us are in drag in some form or fashion, so when I am able to discover what a person’s blockage is, I’m actually always really talking to myself,” RuPaul said, discussing the pep talks he often gives in the set’s workroom. “I see myself in them so I am able to understand where the self-doubt comes from. It’s not something we designed to be part of the show, but it’s an integral part of my personality.”

Last season’s winner, Sasha Velour, the rose-petal dazzler, appreciates RuPaul’s personal investment in each of the contestants. “There’s a kind of intimacy and mentorship that also makes for great TV,” she said. “When RuPaul is looking me in the eye — and telling me, ‘You’re a little too serious. Have you considered just like making a fart joke?’ — at that point I know she has seen me very clearly.”

The realness often goes deeper than that, and can be traced to the show’s modest beginnings in a Burbank basement, where the control room was a closet and the queens hung out in a hallway during deliberations. “It was literally, What the fuck is this?” RuPaul recalled of that first set. Their low-budget surroundings aside, in the first season alone, Ongina revealed she was HIV-positive, Shannel openly discussed her weight problems, and winner BeBe Zahara Benet shared her struggle with the strict gender expectations placed on her at home in Cameroon, Africa.

Even in that freshman season production bubble — before viewers would hear RuPaul’s famous cackle, his “don’t fuck it up!” admonitions, and catchphrases like, “It’s time to lip sync for your liiiiiiife” — BeBe Zahara sensed the show would act as an agent of change. “When we were done filming, I felt that unless you are a coldhearted snake, there is no way that you will not identify with these personas on television,” the 36-year-old Minneapolis resident said. “That’s how I knew this thing was going to be big.”

Never mind the freshman season’s laughable lighting and hazy lens filters — the crew literally greased up the camera lenses because RuPaul admittedly “wanted to make sure that there were no rough edges, especially when it came to drag queens.” One first-season fan was so taken by the new faces on TV, she didn’t notice how fuzzy it all looked on her screen. “It’s funny going back and seeing how blurry all the footage was and how orange it looks,” season-nine winner Sasha Velour recalls. “At the time, I remember watching it and being so shocked to see people who were that queer-looking on TV. Up until that point, I was dressing up in drag, but I didn’t live anywhere that had a drag bar scene. As the show aired, it started showing up in places, and I took my drag out of the bedroom and onto the stage as a direct result of watching Drag Race.”

For RuPaul, the hardest part of the first season was picking a girl to “sashay away” each week. “I wasn’t really prepared for the emotional roller coaster I would experience in eliminating girls,” he said. “But then after the first season, I realized that even the first girl who is eliminated becomes a star and is world famous, so it doesn’t bother me as much.”

He looks back on the first season as more of a pilot. From there, the show found its voice and rhythm, but not without its obstacles. In the early seasons, producers always felt their ambitions were bigger than Logo’s small cable-network budget allowed. The network, which has has half the audience of VH1, wasn’t even rated by Nielsen in the show’s first season. (The second season of the show averaged 440,000 viewers.) Clearing some of the music RuPaul wanted was particularly challenging, as was making the set as glitzy and glamorous as possible. “When we got Whitney Houston’s ‘It’s Not Right But It’s Okay’ for last season’s finale, we were all ahhhhh!” Barbato said. “After that, all the streams for Whitney’s songs went up. We are selling product now.”

By the time the third season rolled around, the producers hit their first major production disappointment: Raja was leaked as the winner online before the finale aired. “I was so angry about that because I think it’s just rotten,” RuPaul said. “But I woke up one morning and I was in that weird time between sleep and waking and it occurred to me in that moment to shoot three different endings. I thought, That will fix those motherfuckas! So no one knew who won season four until it came on television.”

The fourth season stood out for more than its surprise ending. The prize money grew to $100,000, from $20,000 in season one, and the world met Sharon Needles, that cycle’s winner. “She introduced a gender-fuck style of drag and did it flawlessly and in a loving, heartfelt way,” RuPaul said. “It felt like we turned a corner.”

That was the year that seventh-season winner Violet Chachki, who was 21 when she competed and conquered the runway with her extreme confidence and sense of style, started thinking about auditioning, even though she had been watching it since she was in high school. “Season four was the turning point for a lot of people,” she said. “That’s when drag became introduced more as an art form, and it became really, really popular within the gay community. The drag that was represented was different, refreshing, and new. You could see that the girls really started to make money, and it started to become more of a business.”

Before she appeared on Drag Race, Violet Chachki worked in a pizza restaurant and performed in drag four or five nights a week just to get by. “I was making enough to survive, but it wasn’t anything like the kind of budget I’m getting now,” she says. “It’s just crazy to compare the two, you know? It really does change your life.” She’s not alone. Thanks to the show, and the success of DragCon, which will be held in New York for the first time next month, many Drag Race alum are making over $100,000 annually touring, selling merchandise, recording, and in endorsements. “These girls are huge stars all over the world,” Barbato added. “It’s crazy.”

As the show blew up internationally via Netflix (it began streaming worldwide in November 2013 and is now available in 30 countries) and gay bars threw viewing parties across the country, Drag Race had become popular enough to court controversy. It hit its biggest one to date in its sixth season when it featured a “Female or She-Male?” challenge, in which the queens had to guess whether celeb portraits were of “biological” or “psychological” women. The game was met with outcry from viewers who found it offensive; Logo responded by issuing an apology, removing the episode from all of its platforms, and also removing the “You’ve Got She-Mail” challenge intro from new episodes. RuPaul and the producers issued a joint statement at the time: “We delight in celebrating every color in the LGBT rainbow. When it comes to the movement of our trans sisters and trans brothers, we are newly sensitized and more committed than ever to help spread love, acceptance and understanding.”

Reflecting back on it, RuPaul doesn’t indicate that he would’ve done anything differently. “I was upset with the fact that people would think our intention was malicious,” he said. “Our show has always come from a place of love and the people who called us out, they knew our position was a place of love. They intentionally misinterpreted our intention to further their cause and to bring attention to themselves.”

To replace the segment, RuPaul came up with a new intro to the mini challenges, which premiered in the seventh season and became an instant classic: “She done already done had herses.” He had overheard a girl at Krystal Burgers in Atlanta say the phrase one night over 30 years ago when another girl tried to pick up her bag of food, and he never forgot it. “The proper English way of saying that is, ‘No, she has already had hers,’” RuPaul recalls. “When I heard that, I thought, oh my God, I’ve got to write that down.” Campbell laughs thinking about the phone call with network executives to let them know what RuPaul’s new line would be. “They were like, What? And I was like, Trust me,” Campbell said. “What we’ve shown, I think, is this beautiful thing — what attracts people also is against what you’re supposed to be doing. It’s like if your insecurities or feelings were on the outside.”

RuPaul sees the controversy as just another example of the show’s ability to adapt and build upon itself. “The producers and I, we are also crafty queens, and we know how to turn something into something even better,” he adds. “Somebody wanna steal our ideas? Go ahead! We got plenty!”

While Drag Race itself has borrowed from other reality-show formats — Project Runway, American’s Next Top Model, and even a failed World of Wonder show ¡Viva Hollywood! — RuPaul is alluding to the idea that straight culture has taken from gay culture. Drag Race has most notably influenced other popular shows that now feature various forms of lip-sync contests. On The Tonight Show, celebrities and Jimmy Fallon battle it out in a lip-sync competition; on The Late Late Show celebrities compete with James Corden in rap battles. Both of those segments have led to the creation of stand-alone shows: Spike’s Lip Sync Battle and TBS’s Drop the Mic. Although Fallon and Stephen Merchant have said the idea for their lip-sync competition did not evolve from Drag Race, lip-syncing has been intrinsic to drag culture for decades.

What isn’t as easily replicable is the show’s heart. Violet Chachki says she is still taken aback by how much the show makes her cry as the queens share their pain and struggles with identity, family relationships, loss or other personal issues. “I mean, it happens all the time,” she said. “I know these people and I know the show and I know how it works, but here I am tearing up watching a show that I’ve been on. It’s really powerful stuff.”

It happens behind the scenes, too. When Roxxxy Andrews broke down on the runway in the fifth season and spoke about being abandoned by her mother at a bus stop, everyone became emotional, including RuPaul. “People in the control room will be crying, but nobody is acknowledging it,” Barbato said. “There’ll be a moment where the control room just goes silent.”

It’s the one aspect of the show RuPaul says he did not foresee that afternoon in the pool. “I didn’t know how poignant and how deep the show would be,” he said. “I knew that we were going to celebrate the art of drag, but I didn’t know the several levels of importance the show would have. It means a lot to me because I’ve been famous for many years. I’ve done very well and made a great living at it. But, ultimately, all of that really does fade away, and what you’re left with is what you did to be of service to human beings on this planet. And I feel I’ve been a part of something that has been of service to humans on this planet because of our show.”