In early January, the novelist Dennis Cooper turned 64. As a birthday present to himself, he dedicated a post on his popular blog to the late French filmmaker Robert Bresson. Cooper considers Bresson — an art-house favorite renowned for movies of austere and inscrutable beauty like Mouchette and L’Argent — to be his favorite artist of the 20th century in any medium, and he’s frequently acknowledged the director’s influence on his own work. The epigraph for Cooper’s 1994 novel, Try, is taken from an observation about actors in Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematograph and serves as a skeleton key for all of Cooper’s early books: “The thing that matters is not what they show me but what they hide from me and, above all, what they do not suspect is in them.”

Cooper, who now resides in France after being a lifelong Los Angeleno, has for decades been one of the country’s most controversial novelists, loosely affiliated (or just lumped in) with a couple generations of so-called transgressive writers, from Kathy Acker to Bret Easton Ellis. Cooper’s fiction, which includes the novels Closer, Frisk, and The Marbled Swarm, is more accessible than Acker’s and more tender and complex than Ellis’s, and it can be just as disturbing as either — his books are populated by damaged, drug-addled queer teenagers and predatory older men, with vague plots that hinge on graphic, occasionally horrific, fantasies of sexual violence. For this, The Village Voice in 2000 called Cooper “the most dangerous writer in America,” but that sobriquet doesn’t communicate how Cooper’s lurid subject matter provides camouflage for a radical, rigorous exploration of novelistic form and language. Now, however, Dennis Cooper is done, or almost done, with being a novelist — he is reinventing himself in the model of his idol Bresson.

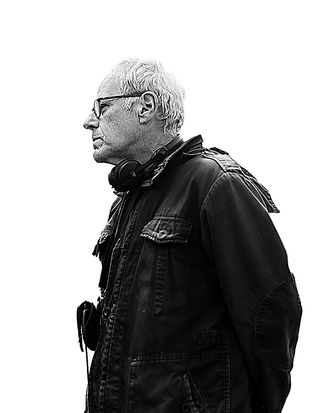

Which is why, a few months after his 64th birthday, in the seaside town of Cherbourg, France, Cooper was holed up in an artists’ residence that caters to circus performers, attempting to make his own film of austere and inscrutable beauty. The project he was working on isn’t Cooper’s first movie — in 2015, along with his collaborator Zac Farley, he co-wrote a collection of abstract, quasi-pornographic short films called Like Cattle Towards Glow — but the new film, titled Permanent Green Light, is a more ambitious, more conventional undertaking. The $160,000 budget is impossibly tiny, but it’s about four times what Cooper had for Cattle. And this time, he’s working with a decent-size professional crew and actors who have a bit of experience. The screenplay, which he co-wrote with Farley, turns on a young man’s obsession with blowing himself up so spectacularly as to make his death beside the point. One inspiration for the film was the story of Jake Bilardi, an Australian teenager believed to have died while taking part in an ISIS suicide bombing in Iraq in 2015. “The story really intrigued me,” Cooper says. “If he didn’t care about ISIS, why did he do this? And if he wanted to kill himself, why was he so elaborate about it?”

In person, Cooper is as sweet and laid-back as his work is dark and difficult. On set, he spends most of his time working with the actors, many of whom are in their teens and 20s, guiding them gently through the profound, sometimes perplexing emotions they need to exhibit. The shoot’s a tight 12 days, and they’re shooting out of sequence, so his notes to the cast are often detailed reminders about their mental states at that moment. On day four, when the actors gather for a scene where their characters attend the funeral of an adolescent girl, Cooper takes aside Benjamin Sulpice, the 20-year-old acting student who’s playing the lead character. “This is where everything changes,” Cooper says to him. After Sulpice completes one not entirely satisfying take, Cooper approaches him again and tries to focus him. “Benjamin, you’re not inside the character,” he says. “You’ve got to get inside there.” Sulpice nods.

Though he’s always collaborated widely within the art and literary worlds, Cooper found that, once he’d moved to Paris, he had a newfound zeal for group projects, teaming up frequently with the prolific French-Austrian choreographer Gisèle Vienne. This was owed, in part, to the isolation of being in Paris and not speaking French, but he was also ready to take a long break from fiction. “I was just at a point in my life,” he says, “where I really wanted to do something new and completely scare myself.”

Speaking over Skype while in production, Cooper wasn’t exactly scared, but he was kind of frustrated and cranky (and fighting a bad cold). Working with other people is great, though not when those people are telling him he can’t do stuff. They’re halfway through the shooting schedule and have completed only a third of the script — scenes are constantly being relocated, shots simplified. The next day they have to shoot the film’s climactic scene — an explosion — and Cooper’s keenly aware of how difficult it’ll be. “Not only is the setup really complicated,” he says, “and not only are we trying to do more than time allows, but Benjamin has to do a lot of really important stuff. He has to go into a lot of very intense, deep spaces. All day. For 12 hours.”

By the end of July, Cooper and Farley were finishing up their picture edit on the film. For the most part, it was going smoothly, though Cooper still occasionally struggled with finding the kind of creative consensus that pretty much characterizes feature filmmaking. When writing, he seldom shows his fiction to anyone before it’s finished, and so he was unusually combative when revealing the film as a work in progress. Their producer came by to see an early cut and said he didn’t like what Cooper considers the film’s most important scene, but Cooper wouldn’t budge. “That is a perfect, sublime scene,” he said to the producer, “and no one is touching it.”

Cooper and Farley have final cut, so if all goes according to plan, they’ll submit Permanent Green Light to the Berlin International Film Festival, where they hope it’ll premiere in February. As strenuous and difficult as making the film is, it has had the welcome effect of renewing Cooper’s creative energy. “It reminds me of writing fiction when I was first starting out,” he says. “We’re really just finding our way into it and trying all kinds of stuff.” He hasn’t completely abandoned fiction — he’s written three-quarters of a first draft of an untitled autobiographical novel that he says is completely different than anything he’s ever published before. But that’ll be the last one, he believes. “I’ve written nine novels. That’s enough. I think I’m out of ways to write novels that are challenging to me. But these other forms are where I can be the artist I want to be.”

*This article appears in the August 7, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

*The original version of this article incorrectly stated that Cooper was a co-director on Like Cattle Towards Glow.