When Lani Sarem was a little girl, she had a fantasy. Like so many little girls and boys, she wanted to be a star, and for a brief moment this summer, her dream seemed poised to come true. She was a New York Times best-selling novelist, and if everything continued according to plan, she would soon star in a major motion picture based on her book. But then the dream ruptured. It was over almost as soon as it began.

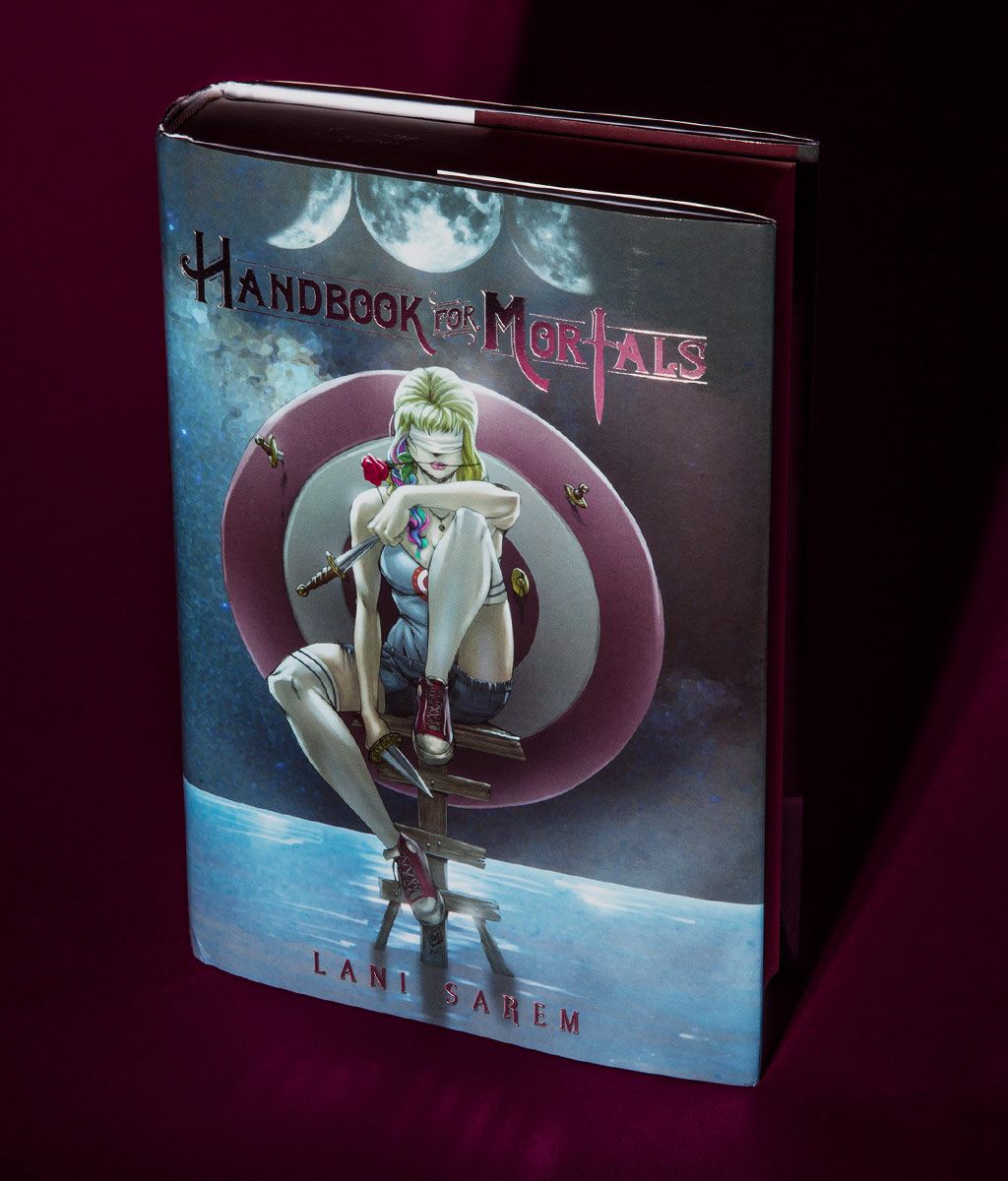

Sarem, in case you missed the headlines, is the author of Handbook for Mortals. In August, her book suddenly appeared at the top of the Young Adult Hardcover Books best-seller list. Apparently she had sold more than 18,000 copies in the first week alone. A Hollywood movie that sells 18,000 tickets in its first week is a catastrophe; a YA book — any book, really — that sells that many copies within a week of publication is a sensation. And yet, hardly anyone seemed to have read her book. No one had reviewed it in any of the usual blogs or publications. If anyone in the publishing world had even heard of Sarem, they didn’t say so. Amateur detectives — several of them YA authors themselves — soon uncovered evidence that Sarem, or someone working with her, had bought the book in bulk, presumably in order to get it onto the best-seller list. The reaction on Twitter was swift and unsparing. People called her a con artist and a cheat. They ridiculed her writing. Former employers disparaged her. She was accused of plagiarizing the book cover, white entitlement, and of hiring ResultSource, a company that runs cynical marketing campaigns aimed specifically at gaming the best-seller system. Within 23 hours, the Times removed the book from the list, acknowledging in a vague statement that they had discovered “inconsistencies in the most recent reporting cycle.”

“If I were an 18-year-old, I would have probably killed myself,” Sarem, now 35, told me a few weeks ago over a glass of Chardonnay at the Sheraton JFK Airport Hotel. Still, she made it clear she doesn’t have many regrets: “There’s good and bad in what occurred.” Yes, her reputation had gone up in flames. But now she’s more famous than ever.

I met up with Sarem almost two weeks after her book was removed from the list. In interviews she’d given before our meeting, she claimed she hadn’t participated in any plot to game the system, and wasn’t even aware of one. She blamed her downfall on the YA Establishment — the reviewers and authors and bloggers who had shamed her on Twitter. They didn’t like her, she argued, because she was an outsider. Sarem hadn’t sent them advance copies of her book — instead, she had promoted it herself and with friends, selling it at comic conventions. It was a “witch hunt,” she said.

Was it possible there was some truth to her claim? None of the writers weighing in on the controversy had met Sarem in person. Besides, best-seller campaigns of all sorts — ResultSource-aided and otherwise — are not all that uncommon. I wrote her a message saying I wanted to hear her perspective, and Sarem wrote back that she was flying from her home in Vegas to a comic-con in Nashville and would be willing to make a detour to New York for the meeting. I suggested a bar in Manhattan; she proposed I come out to the Sheraton JFK Airport Hotel instead. Sarem, I’d learn, belongs to the Sheraton Club, which offers its members access to a sort of VIP lounge where you can get free chicken fingers and dumplings that are mysteriously filled with cheese.

In the lobby of the Sheraton, the elevator doors parted to reveal Sarem in a flowing blouse, a hopeful smile on her face. Her long tresses were blonde on top and pink and blue at the ends. Upstairs in the lounge, she began to tell her life story. Her father died when she was a baby. She and her mother moved often, ten different states in Sarem’s first 19 years. Wherever they went, Sarem tried out for local theater productions and TV commercials, but all the best roles went to other girls. She realized that if she wanted to be a star, she’d have to write the script herself. “I wanted to forge my own path, and I ended up in Vegas,” Sarem said.

For about a decade, Sarem paid the bills by taking on entertainment gigs in Vegas and on the road. She worked at David Copperfield’s theater for a while. She became the manager of a band called 100 Monkeys and the ’90s jam band Blues Traveler. In 2010, when she was 28, her fiancé broke up with her. Three weeks later, she began writing the first draft of a screenplay for Handbook; she found it cathartic. Four years after that, she decided to turn the screenplay into a book. “When I started writing, I really wanted all the things that I couldn’t have at that moment,” she said. “I wanted somebody’s love story to work out. I wanted this character to have all the things I was lacking, and then live vicariously through her.”

The character in question — the protagonist and narrator of Handbook — is a young woman named Zade. In many ways, Zade is just like Sarem. She dyes her hair in the same fun colors. She leaves her home in a small Southern town to work in Vegas. Unlike Sarem, Zade always gets what she wants, and she doesn’t have to struggle for it. As a result, the book doesn’t offer much in the way of conflict or plot. Zade auditions for a magic act and is instantly hired; men meet her and fall in love at a glance. Some of her triumphs are almost touchingly modest. At one point, she goes on a trip to the mall where she runs into Vegas mainstays Carrot Top and Wayne Newton. Newton tells Zade he’s excited about watching her perform. Carrot Top shares his real name and invites her to come backstage to hang out anytime. That’s the entire exchange. Sarem has compared her book to Fifty Shades of Grey, another novel by an industry outsider that many have derided as a silly wish-fulfillment fantasy. But Fifty Shades, whatever you think about the writing, allows women to imagine themselves having kinky sex with a billionaire. Handbook features some light petting, but mostly it offers the kinds of dubious thrills that come from making small talk at a mall with Carrot Top.

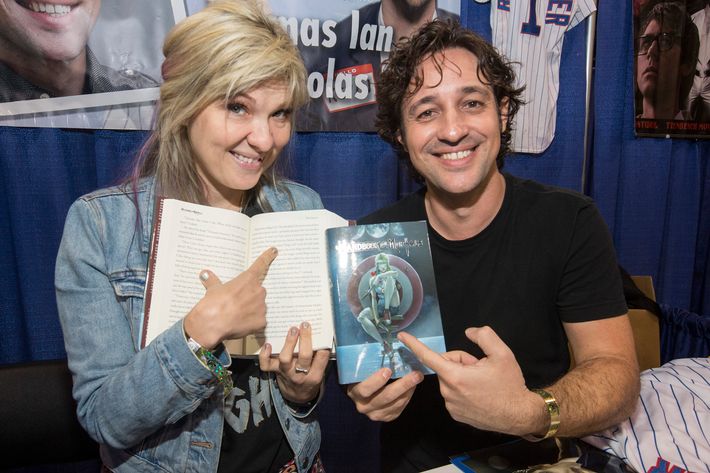

At the Sheraton, Sarem didn’t attribute the book’s phenomenal success to the quality of her writing. She attributed it to someone named Thomas Ian Nicholas. Maybe you’ve heard of him. If so, you were probably a kid in the ’90s. He starred in the 1994 kid flick Rookie of the Year and 1999 teen hit American Pie (and its three sequels). Sarem met him a few years back. At the time, she was trying to put together a band of actors who are also musicians. (The lead singer of 100 Monkeys played Jasper Hale in Twilight.) That project never came together, but she showed Nicholas the script for Handbook and promised him a supporting role and a producer credit if he helped her get it made. Nicholas thought the project had potential, and they became business partners. Later, I spoke to Nicholas as well and asked what drew him to the script. He mostly spoke about himself, saying he was from Vegas and that his great-uncle was John Scarne, a Vegas magician who served as Paul Newman’s hand double in The Sting. “Those two elements were a big part of why I was intrigued,” he said.

Sarem jumped in. “You also liked the little twists and stuff that I’d written,” she offered.

“Yeah,” he said. “When Lani liked all but one of my notes, that got me interested in getting involved in the project,” he added, “because you want people who value your opinion.”

While the two of them were taking meetings, trying to get funding for the movie, a friend in Vegas suggested that Sarem also turn the screenplay into a book. This struck her as a shrewd idea. “A lot of the things that grow to be the biggest tend to have both a book and a movie,” she explained. “If people say they don’t look at the business perspective of things, they’re lying. From the business perspective, it made sense.”

Adapting the screenplay was challenging. “My grammar isn’t always the greatest,” she told me. Sarem had to hire three different editors to help pull the book into shape. She took pains to make sure it mirrored the script as much as possible. According to a person who read both the script and the book, Sarem said she had promised Carrot Top a part in the film, therefore she had to include him in the book as well.

Despite these challenges, Sarem finished a draft she felt good about. At the beginning of 2017, Nicholas took it to his friend, Clare Kramer, who plays the villain Glory in season five of Buffy, and her husband, a producer, and asked them if they wanted to publish it. They had never published a book before, but they ran the pop-culture website GeekNation and were happy to lend its name to the project. After that, Sarem says, she and Nicholas began taking early orders for the book at Wizard World conventions and other comic-cons where Nicholas was already a regular. The book, I must stress, had not yet been printed. For several of the conventions, Sarem didn’t even have a cover she could show people. But she insists the buyers didn’t care. As she explains it, Nicholas would sit at a booth decorated with Rookie of the Year and American Pie memorabilia, and convention guests would wander over and ask him what he was working on next. He’d tell them about Handbook and say that for $35 he’d send them a copy after it was published. He and Sarem would promise to autograph it.

Sarem characterized these customers as “collectors” above all else. “Some of them will probably never even read the book,” she said, “but that doesn’t matter as long as they buy.” She estimates they sold almost 13,000 books in this way — an average of more than 2,100 per convention. The rest of the 18,000 she says she sold through her website and at Wizard World Chicago right after the book came out. (They had the actual published books stacked on the table for that one.)

I asked a few comic-con regulars if they thought Sarem’s story of how she’d sold all these books was plausible. Charlie “Spike” Trotman, a writer who runs the largest comic-book publisher in Chicago, was highly skeptical. Neil Gaiman, she wrote, could ship 500 books to a comic-con and sell them all – but that’s on the very highest end of what anyone might hope to sell at a con. “I, and other people, would have noticed this bizarrely, wildly popular PROSE book that people who are coming to conventions explicitly to buy COMICS simply can’t say no to,” she wrote. Maryelizabeth Yturralde, co-owner of Mysterious Galaxy, a bookstore that specializes in mystery, fantasy, horror, and science fiction, said a big-name author like George R.R. Martin could perhaps sell hundreds of books — not thousands — in a day at a comic convention, and even then, only on the best of days. “I’m not sure what known reality her books reached all these readers in,” she said. “But it’s not one I’m familiar with.”

Sarem and Nicholas had already heard all this, and they had an answer: Sarem sold so many books because she had a “famous” person right there with her at the booth. “The comic-cons are very celebrity-focused,” Nicholas said. Most writers are sequestered in their own area, he explained. “But Lani’s at my booth.”

Now, if the actor who played the virgin with the girlfriend from the American Pie franchise can sell roughly four times as many books as someone like Neil Gaiman or George R.R. Martin just because he offers to autograph the copies, that says something pretty sad about the state of American culture, but it does not constitute a scam in and of itself, unless you consider consumerism, nostalgia-peddling, and celebrity worship to be scams. The scam — one of them, anyway — was in the way she fulfilled all those comic-con orders. At the Sheraton, Sarem admitted she had not been entirely truthful in her first round of interviews after the scandal broke. To fill the orders, she said, she had indeed called up bookstores and ordered her books in bulk. (She later made a similar point in an op-ed in Billboard.) Before placing those orders, she first asked if the bookstores reported their sales to the Times. Not all bookstores do. The methods the Times uses to compile lists are as mysterious as the rites of a medieval religious order, but what the Times does make clear, in a statement on its website, is that it bases the rankings on retail sales. Convention floors don’t count as retailers. As Sarem made clear to me, she wanted the Times to count her supposed convention sales, so instead of ordering the books directly from her publisher, she took the stealthier route. “I wanted to hit the list,” she admitted. “Doesn’t everyone? It’s crazy to think not.”

But the bigger question was how would a first-time author, a first-time publisher, and one of the virgins from American Pie have come up with this scheme? Did they have any help?

YA author Phil Stamper, the first to tweet that there was something odd about Handbook’s ranking on the list, suspected that they did. He’d heard from a number of booksellers around the country who said they had received calls from people placing bulk orders for Handbook. At least two of these callers had provided the booksellers with email addresses containing the domain name of a company called Author Book Events. It had no website, perhaps because it did not exist. One of the calls, however, seemed to hold a clue. The buyer asked the bookstore employee to get in touch with his assistant, who would place the order for him. He gave the employee his assistant’s email address, which contained a domain name that sounded innocuous enough — authorbookevents.com. And then, like a poker player accidentally showing his hand, he identified the assistant as Krista Tetreault and told the employee he could reach her at a 760 phone number. As a friend of Stamper’s pointed out on Twitter, if you google “Krista Tetreault” and that Southern California area code, the first match that comes up is a ZoomInfo page for an employee of a company called ResultSource.

If you have heard of ResultSource, it is probably in connection to one of several different scandals that have made the news over the years. Maybe you remember the pastor who used church funds to buy his way onto the best-seller list in 2014, or the California gubernatorial candidate Steve Poizner, whose memoir turned up unsolicited in the mailboxes of hundreds of California residents in 2010. Up until a few years ago, ResultSource was strikingly transparent about its mission. “We don’t sell vague promises like ‘increase your awareness,’” the website once read. “Instead, we create campaigns that reach a specific goal, like: ‘On the bestsellers list’, or ‘100,000 copies sold.’” After the pastor debacle, however, the site went dark.

At the Sheraton, I asked Sarem when she’d hired ResultSource; she denied working with the company at all. If that were true, I countered, then why had she thanked three employees of ResultSource in the acknowledgements of her book?

She admitted then that she had talked to them, but only to solicit their advice. “I was trying to figure out the book world because it’s very confusing,” she said. I told her I knew for a fact that someone working for ResultSource had placed a bulk order for copies of Handbook. I’d seen the order slip myself. Her face went pale and her eyes went wide and the silence stretched before us.

A few days later, I had another conversation with Sarem. She’d promised a response to my question about ResultSource. Nicholas was on the line as well — they were together in Nashville for another convention. Sarem began to argue that the Times’ system for evaluating best sellers was snobbish and outdated and unjust, and asked why nobody was talking about that, a point she’d made in that Billboard op-ed after our meeting at the Sheraton. In the Billboard piece, she admitted vaguely that she did buy the books in bulk, but since “real people” (the comic-con buyers) supposedly ended up with the copies, she believed the steps she took were “well within the rules.” (She has also made this point in a similar op-ed in the Huffington Post.)

Over the phone, Sarem and Nicholas went a step further, admitting that they had, in fact, hired a company to help them orchestrate a targeted bulk-buying campaign. “I can’t tell you who we hired,” Sarem said, “because I signed an NDA.”

“I don’t think we’re necessarily breaking rules so much as abiding by them,” Nicholas said. “Because there was no way to make our sales count without running them through the stores.”

I asked Nicholas and Sarem if they felt discouraged by the recent uproar. Short answer: no. “If I listened to the word no then I wouldn’t be in the entertainment business for, now, 31 years,” said Nicholas. “If we listened to people telling us no, women would probably not even have the right to vote,” Sarem added.

Sarem did say that if she could do it all over, she would send advance copies to people in the YA community. Other than that, she’s not sure she would do anything differently. She and Nicholas said they haven’t ruled out using the same strategy to sell the second book Sarem is planning for the series.

They both remain mystified about why the Times removed Handbook from the list. Throughout the conversation, Sarem and Nicholas insisted they had sold all 18,000 books to “real people,” the comic-con customers. I asked Sarem if she could show me proof of those sales. After six days, she sent me a 269-page document. She said the list showed “almost 10,000 orders of our presale list with data info protected.” The document is a PDF of a spreadsheet; there’s no way to prove or disprove its authenticity. It contains no information about when or where the customers placed the orders, nor does it give the names of any customers; it only says what town or city they’re from, when the books were shipped, and whether the customers paid in cash or credit card. (If the document is real, the vast majority paid in cash.)

Since our meeting I’ve talked to two people who told me they heard Sarem casually discussing plans to buy her way onto the Times’ list this past spring. One of them, who asked to remain anonymous because she is still in touch with Sarem, said the author told her on two different occasions that she planned to push Handbook onto the Times best-seller list by buying copies in bulk and handing them out for free to convention attendees.

Still, there may be something to Sarem’s claim that she has been punished for being an outsider. Earlier this week, I got a message from an employee at an independent bookstore in California that had handled one of Sarem’s orders. He’d heard I was working on this story and wanted me to know “how not uncommon” it was for authors and publishers to buy books in bulk in order to boost their rankings. “When the big publishers do this, no one ever finds out,” he wrote, “because it doesn’t stick out like a sore thumb, the way her thing did.”

I asked him to elaborate, and he sent back an unsettling note. The only reason his bookstore reports its sales to the Times each week is because occasionally someone will call to ask if it does, and will then buy 60 or 70 books at once. “Selling 70 books at a pop, even at a discount, will turn a sub-par sales day into a ‘sales were up today!’ kind of day,” he said. “Bookselling,” he added, “is a barely head-above-water kind of business.”

Perhaps that explains why a company like ResultSource is still doing business, even as it stays in the shadows. Recently, a clerk for San Diego County confirmed for me that Author Book Events is indeed a fictitious business name (the official term) for ResultSource Inc. ResultSource did not respond to my request for comment. But the company is still around, and so long as writers desire the title of best-selling author, and publishers see an advantage in helping them attain it, and bookstores depend on bulk-buying campaigns to keep their doors open, ResultSource Inc. seems likely to endure.

Several questions remain unanswered. If Sarem didn’t sell the books to real people, where did she get the funds to buy them? And even if she did sell them, where did she get the money to pay the company that carried out the bulk-buying campaign? According to Forbes, ResultSource typically charges a fee of more than $20,000. Sarem told me she hired the company (the one she wouldn’t name) using profits from the Wizard World sales.

In the weeks since our conversation, Sarem has made the most of all the free publicity this scandal has provided. In a flyer for an author event at a Barnes and Noble last week, she invited readers to meet the “best-selling author” of the famous book that was “No. 1 on the NYT best seller list for 23 hours.” (She also offered attendees a chance to win a baseball signed by Nicholas.) Whether or not this will attract new customers remains unclear. According to NPD Bookscan, her numbers have steadily declined since her first week of sales, dropping from five digits, to four, to three, and then to only two. For the week ending September 24, the most recent week for which data is available, she’d sold just ten books. Still, as another fantasy writer once put it, hope remains while the company is true. Sarem and Nicholas are scheduled to appear at four more comic-cons this year, and the Wizard World organizers have invited them to attend all 17 conventions scheduled for next year. Sarem says they will be at as many as possible.