“So yeah, I mean, honestly? I’ve been fucking ecstatic,” Kevin Smith says in a rusty baritone, his messy, pot-odored SUV soaring through Southern California. “There’s a disconnect for me when people are like, ‘You need to do this, that, or the other thing,’ or ‘What happened to you?’ The one that kills me is ‘What happened to you?’ I’m like, ‘What happened to me?’” He smiles. “Like, ‘I don’t know, I just did a thousand more things than I ever did back in the day.’ “

He’s answering an odd question that I posed a few moments before. After more than an hour of marathon gabbing on a drive from Los Angeles to Anaheim, his raw, glowing happiness and dearth of complaint about much of anything prompted me to ask him when his life became perfect.

He didn’t laugh or wince at the question. Nor did he say the perfection arrived when he wrote and directed the string of films for which he is still best known, the Gen-X touchstones Clerks, Mallrats, Chasing Amy, and Dogma. “I think I hit it a few years back,” he says after a pause. “And it was when I started diversifying. When I moved away from just film. When I started doing whatever the fuck caught my fancy.”

A great many things catch Smith’s fancy. To call him a filmmaker as of now would be either misleading or misguided. Sure, he still makes movies on occasion — weird ones, deliciously weird, completely unlike the slacker comedies that made him the peer of Tarantino, Linklater, and other indie luminaries — but they’re intermittent affairs. Nowadays, his primary stream of income comes from live performances to sold-out theaters, ones where he typically just gets on stage and talks about whatever for a few hours.

His other outlet for work is similarly based on rambling: podcasts, six of which he personally hosts — discussing topics ranging from Batman to addiction recovery — and many more of which he distributes as part of his imperial “SModcast” brand. He produces and appears on an AMC reality show that just got renewed for a seventh season. He preaches to a congregation of 3.24 million on Twitter and 2.8 million on Facebook. He tours the world. He’s in the business of giving his followers more and more Kevin Smith, and business is quite good.

“Most of my shit is just my mouth,” the 47-year-old says, gesticulating broadly with a hand whose wrist bears the tattoo IN SMOD I TRUST. “As I told my mother this weekend: quite like a whore, I use my mouth on people for money.” There’s our Kevin, constitutionally incapable of keeping it clean, and often pushing the boundaries of good taste. He has a well-known tendency to lay on the filth: Clerks was lewd enough to just barely escape an NC-17 rating, and even now, he heavily seasons his lucrative monologues with multitudinous blowjob jokes, astoundingly vivid stories about making love to his wife, and a startling number of remarks about his allegedly miniscule penis. Non-fans could be forgiven for eschewing a SModcast or placing one of his books back on the bookstore pile, turned off by the use of naughty and not-necessarily-sensitive language.

But there is method to this lewdness. After all, Smith changed American popular culture. In just a few years in the 1990s, he simultaneously catalyzed no fewer than three tectonic shifts: introducing hardcore geekdom to Hollywood (virtually no one was doing deep-cut superhero references on screen before he was); enshrining the travails of the emotionally stunted, American beta-male manchild (Judd Apatow practically owes him royalty checks); and establishing a robust and refreshingly open presence online (Smith was fighting trolls before you ever heard the word blog). He may not be in the mainstream cultural conversation the way he once was, but he, more than many of his contemporaries, helped dictate the terms of that conversation.

However, one can’t avoid the fact that his more recent work is, among cineastes, at best disdained and at worst loathed. That’s to be expected, given that Smith waged a years-long holy war against critics that culminated in a stunning 2011 screening during which he took to the stage like a pro-wrestling heel and told the film establishment that it could go screw. That approach certainly didn’t help with the reception of his last three flicks, Red State, Tusk, and Yoga Hosers, all of which were box-office flops and objects of derision from the commentariat.

And yet, though previous iterations of Kevin Smith used to go on and on about his foes’ hatred and paid it back with interest, I was surprised to find that he no longer appears to care about any of that. He seems largely unbothered by the things people have said about him and feels a little sheepish about having been so mean to the ink-stained wretches he once railed against. And why should he be angry? He is, for the first time in his four and a half decades on the planet, a very happy man.

However, therein lies the danger. “Happy people don’t really make great art, you know?” Smith says. “Great art comes from sadness and misery. I’m 46” — he has since turned 47 — “I don’t wanna fuckin’ go through negative shit anymore.” Instead of trying to make that great art, he decided years ago to aim for art that satisfies both himself and his rabid fanbase, and you can argue that that decision took him out of the cinematic zeitgeist while his ‘90s indie compatriots continued to set the pace.

But now, he’s making his first tentative steps back into the mainstream with a series of major TV-directing gigs, a deal to create his first true comic-book screen adaptation, and a risky cinematic revisitation of his most famous creations, Jay and Silent Bob — the latter of whom is played by the creator, himself. In other words, Kevin Smith has the chance to re-enter the race for mass appeal. The question is: Can he catch up with the world he helped create?

Actually, maybe the question is: Does he even want to? After all, Kevin Smith has used his second act to craft a new-model utopia of modern fame, one built on niche interests, a direct line to fans, and an unmistakably unique voice. At one time, Smith seemed to represent a new model of filmmaking: cheap, lewd, bracing, and provocative. Now he’s again at the center of a new model: the business of niche audiences and narrowcasting directly to fans. He’s no longer talked about in conversations about the future of filmmaking. But he just might exemplify the future of celebrity.

By now, Smith’s origin story is well-known and long-mythologized, not least by Smith himself. “I am a product of Don Smith’s balls” is how he kicks off his fourth book of nonfiction, 2012’s Tough Sh*t: Life Advice from a Fat, Lazy Slob Who Did Good. The zygote fertilized by those testes was subsequently born into a “government-cheese-eating, lower-lower-lower-middle-class home” in North Jersey. His creative inspiration came from the often-tragic example of his father. “My old man worked for the post office and fucking hated it,” Smith tells me. “It was the constant example of seeing how much my dad hated legitimate work that made me be like, ‘Well, clearly that’s not going to be for me. Maybe it’s worth taking a shot in make-pretend.’ ”

On a trip to Manhattan’s Angelika Film Center, Smith and a friend saw Richard Linklater’s seminal 1991 indie flick Slacker — and the twentysomething Smith saw his future. “One Kevin Smith stepped out of the vehicle and headed into the Angelika Film Center, but two hours later, a very different Kevin Smith would emerge,” Smith writes in Tough Sh*t. He was particularly blown away by how Linklater had ignored Hollywood in favor of shooting local folks in his hometown.

After a short-lived stint in film school in Vancouver, Smith headed back to Jersey, rounded up his buddies and some local community-theater actors, maxed out a bunch of credit cards for financial backing, brought cameras into the convenience and video stores after he finished his shifts and shot Clerks. It got into the 1994 Sundance Film Festival, won the interest of Harvey Weinstein, and by the end of 1994, Smith — a complete nobody in horrible debt just a few months prior — was held up as a generational spokesperson.

Smith’s sophomore effort, Mallrats, was a theatrical flop, but a cult hit on the home-video market. In 1997, he released his most acclaimed film of all, Chasing Amy; and then, in 1999, the supernaturally minded Dogma, which courted buzz-inducing controversy for its envelope-pushing depictions of Catholicism. He was asked to write a Superman movie. (The story of how that one didn’t come together is a long and hilarious tale that is best consumed by watching video of Smith recounting it onstage.)

All was going well — and then came 2004’s sensitive rom-com Jersey Girl. The film was a bomb and received a critical drubbing. He didn’t forgive the scribe intelligentsia for that, and a new, adversarial relationship began. His next effort, 2006’s Clerks II, made a lot of money, but something had changed. The golden age of his mainstream reputation was over. This didn’t change with 2008’s Zack and Miri Make a Porno or, two years later, his first and only attempt at directing a movie he didn’t write, the buddy-comedy Cop Out.

In this period of difficulty, Smith retroactively realized something about himself, something that has guided his recent reinvention: he’s not, first and foremost, a filmmaker. “Clerks looks like a $27,000 icebreaker, y’know? That’s what it seems like to me. Just the kinda thing where I’m like, ‘Hi, my name is Kevin Smith, and I’d like to talk to you for the next 50 years,’” he said in a 2010 live performance. “It was me ripping open my chest, pulling fatty chunks of my heart out, and slapping it between two platters, and projecting that shit and being like, ‘Do you get it?’ And people would be like, ‘Yes.’”

If he couldn’t do that with mainstream movies, fuck it, he didn’t need ‘em. He was wealthy enough as it was, and besides, he had a new medium for ripping open his chest, one then still in its infancy: podcasts. His longtime friend and collaborator Scott Mosier and he tried their hand at one in 2007, calling it The SModcast (S for Smith, M for Mosier), and were surprised at how big and devoted an audience it snagged. There was never much of a structure. It was just them hanging out, talking about topics such as whether or not the characters on Lost would masturbate on the island. (“Are you like, ‘I’m going on a hike,’ and it’s like a three-minute hike and you’re like, ‘I’m back!’”) It wasn’t for everyone, but then again, Smith was no longer interested in appealing to everyone. Indeed, this privately genial man who had once charmed Hollywood with his self-effacing humor started to develop a reputation as a crank. “I do think that Kevin went through a midlife crisis,” his wife, Jennifer Schwalbach Smith, says of the turn of the decade, and he went through it in public.

In 2010, he was kicked off of a Southwest Airlines flight on the grounds that his choice of seating arrangement hadn’t properly accounted for his size, and he immediately took to Twitter to (plausibly) dispute that accusation and denounce the airline. It was, as you’d imagine, a bit of a disaster, bringing him ridicule both for his complaining and for his body. Today, he calls it the worst thing that’s ever happened to him — “Granted, it’s a very First World problem,” he hastens to add, “and I’ve led a pretty uneventful life if this is the worst thing that ever happened to me” — but the situation was worsened by his inability to be good-natured about it.

To wit: He was invited to appear on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart right afterward, but he declined. “Jon was like, ‘Come on out and we’ll get one of the [airline] chairs and you can fucking sit in it,’ ” Smith recalls. “And it freaked me out. Like, instead of knowing me as I know me now, I wasn’t prepossessed enough to be like, Oh yeah, that’d be smart, let’s do that. The worst thing that ever happened to me happened and I couldn’t make light of it.”

On top of that, he increasingly went after his critics in interviews, public appearances, and social media. “Seriously: so many critics lined-up to pull a sad and embarrassing train on COP OUT like it was Jennifer Jason Leigh in LAST EXIT TO BROOKLYN,” he wrote in a now-infamous series of tweets in 2010. “Film fandom’s become a nasty bloodsport where cartoonishly rooting for failure gets the hit count up on the ol’ brand-new blog. And if a schmuck like me pays you some attention, score! MORE EYES, MEANS MORE ADVERT $.”

Smith’s anger at the world came to a head in one of the more remarkable public events in the history of filmmaking. He wrote and directed an indie thriller about hyper-Christian cultists called Red State and announced that he would auction off the distribution rights to the highest bidder after a premiere screening at Sundance in January of 2011. After the screening, Smith walked onstage with a hockey stick, wielding it with an air of intimidation. He proceeded to give what he would later call “a barn burner of a speech” about how commerce was crippling art. “I never wanted to know jack shit about business,” he declared to those assembled. “I’m a fat, masturbating stoner. That’s why I got into the movie business: “It seemed like the place where fat, masturbating stoners went. And if somebody had told me at the beginning of my career, ‘You’re going to have to learn so much about business, finance, amortization, all that shit, monetization,’ I would have been like, ‘Fuck it. I’m just going to stay home, smoke, and masturbate. That’s too much work, man.’”

His friend, Jon Gordon, announced that the auction would begin. Smith bid $20. “Sold!” Gordon cried. It had all been a con, a publicity stunt — Smith had never planned to let anyone but himself distribute Red State. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he bellowed to the astonished crowd, “when I came here seventeen years ago, all I wanted to do was sell my movie. And I can’t think of anything fucking worse, seventeen years later, than selling my movie to people who just don’t fucking get it.”

Smith also felt that critics didn’t fucking get it, and he didn’t screen Red State for them. Instead, he appealed directly to his fans by touring the country with the film, selling tickets for screenings that featured post-film live appearances from Smith. Though the movie was a near nonentity in the mainstream box office, Smith had cut out the middleman by self-distributing and could sell tickets at a premium for those special appearances, so he made back his budget. And a new business model was born. Kevin Smith was no longer a pitchman for Kevin Smith films. Instead, his films were excuses for people to go out and see Kevin Smith.

Smith followed Red State with an even weirder movie, 2014’s Tusk, which follows the horrifying tribulations of a podcaster (Justin Long) who runs into an aging gentleman (the late Michael Parks), the latter of whom then kidnaps the former and performs amateur surgery to turn him into a human/walrus hybrid. It’s genuinely terrifying and, in depicting the dismemberment of a self-confident podcaster, it’s a delightful little commentary on Smith’s own past and present.

His latest flick, last year’s Yoga Hosers, brought Smith full circle: it’s a spiritual successor to Clerks, one about the quirky adventures of Canadian convenience-store drones played by his daughter Harley Quinn and Johnny Depp’s daughter Lily-Rose. Its climax was Smith’s most incisive self-commentary yet: a Nazi creates a golem that will murder everyone who ever criticized him. “The whole third act of the movie is an apology to critics for acting like an asshole,” Smith tells me. “So much so that the girls, the heroes of the movie, go and save critics from the rampaging monster that the out-of-control artist created. And that dude gets killed by his own art.” Critics didn’t widely accept the apology, and the movie received poor reviews and worse theatrical receipts.

No matter. Smith doesn’t cry over his recent cinematic struggles. He merely smiles and shrugs. Because, you see, he’s become the rare moviemaker to graduate into a life that doesn’t really require making movies.

In order to appreciate the remarkable nature of Kevin Smith’s current productivity, you first need to understand how stoned he is. Over the course of our day together, he smoked no fewer than four joints. He also managed to: fly from Kansas City to Los Angeles; drive himself to a podcast recording (don’t worry, he never smoked while driving); drive himself to Anaheim for a comic-con while doing a 90-minute interview; talk to a sea of reporters; host a mainstage convention panel; mingle with a dozen or so admirers; drive himself back to L.A. while doing yet another 90-minute interview; record a second podcast at his house; drive to a club to record yet another podcast — this one in front of a live audience — mingle with more admirers; then return home to steal a few hours of sleep before waking, baking, and starting all over again. (And reader, please understand: this weed is very strong. I speak from experience. How on earth he manages to function is beyond me.)

Yet function he does, and at a high level. “He has things to say and it does not stop,” Schwalbach Smith tells me. “He’s always been — even before the weed — able to lay his head on the pillow and he instantly falls asleep, and is able to sleep so deeply. Maybe because he has lived a full day pursuing his dreams, writing his emotions, I don’t know what it is. And then he pops back up three hours later, and he’s like, ‘Let’s go!’ and I’m like, ‘Are you fucking kidding me?’ He’s kind of a machine.”

The night before our interview, the Smith machine had been on tour, doing a live taping of Jay and Silent Bob Get Old, the podcast he hosts with Jason Mewes, the eccentric untrained actor who has populated much of Smith’s oeuvre by playing Jay of Jay and Silent Bob. It is, perhaps, the finest of his podcasts — an alternatingly tender and gross affair that brings together two people who have lived life surreal and rocky lives together for decades. The podcast launched in 2010 literally as a form of rehabilitation therapy for Mewes, who had spent many years addicted to heroin and other substances. Smith had the curious and intriguing notion of doing a podcast where they check in on the now-sober Mewes’s progress in front of an audience, to make sure he feels public pressure to stay on the straight and narrow.

His other podcasts are significantly lighter, and that’s sort of the point. Take, for example, our first podcast of the day we spent together: Fatman on Batman. Around since 2012 and currently co-hosted by writer Marc Bernardin, it’s an outlet for Smith to be the Über-geek that he always has been, reacting to all things superhero: movies, trailers, TV shows, comics, news, what have you. Or the second one of the day, Edumacation, in which Smith’s buddy, writer Andrew McElfresh, studies academic topics and tries to teach them to Smith. Or the day’s capper, the wildly popular Hollywood Babble-On, a live show with comedian and radio host Ralph Garman that’s structured like a morning-zoo radio program. Or, of course, The SModcast, which is as engagingly rambling as ever.

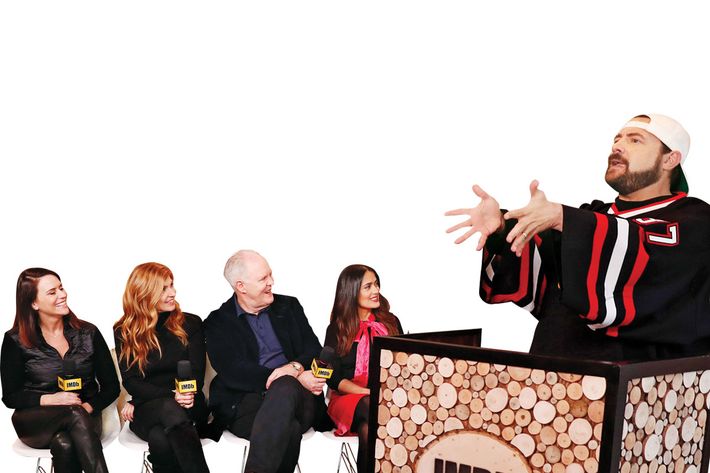

It’s all just about Kevin Smith being Kevin Smith, for the most part. That’s even the case with gigs where the audience never hears him. He’s recently taken up a side career as a television director, helming episodes of The Flash, Supergirl, and The Goldbergs, and he very openly says he doesn’t creatively contribute much, given that the shows are tightly run ships that don’t need his expertise. “I bring no vision, whatsoever,” he tells a gaggle of journalists at the comic-con, which he’s attending to promote his work on The Goldbergs. “But I can make everybody fuckin’ happy to be at work. I direct like a Baptist preacher on coke.”

Smith says he doesn’t need the money that the TV jobs bring him — they offer something even more valuable. “What those are good for is content, because if I’m going to stand on a stage and talk, you’ve got to be relevant and talk about new adventures,” he says. That’s the key: everything comes back to Smith’s talent for and fixation on talking. Directing a TV show, going on a trip, having sex with his wife — it all provides content for him to speak to his devotees in live shows and on podcasts. “Especially at the theater shows, I think he puts it all out there and he doesn’t really shy away from talking about every aspect of his life,” says friend and Comic Book Men co-host Walt Flanagan. “And bringing it honesty, along with humor. I just think it makes an audience just sit there and become fully engulfed in what he’s saying.”

In other words, Smith has transformed himself into the perfect figure for our current media landscape. Audiences have a decreasing tolerance for entertainment that feels practiced and rehearsed — they want people who shoot from the hip, say what they mean, and mean what they say. Smith delivers all of that. In an informational ecosystem where there are far too many chattering voices, people want someone who speaks loudly and directly to their interests and worldview, and Smith and the SModcast empire do that. We’re all forced to self-promote and self-start these days, and Smith is a patron saint in that realm. Even if his time in the spotlight is in the past, few artists have more expertly navigated the present.

And the future is looking good for him, too. He’s currently working on a new Jay and Silent Bob movie, Jay and Silent Bob Reboot. He’s currently developing a TV adaptation of Todd McFarlane’s comic-book series Sam and Twitch, his first honest-to-god comics adaptation after a lifetime of loving the funnybooks. There’s a non-zero chance that this post-midlife-crisis Kevin Smith will re-enter the lives of Joe and Jane Q. Public and show them why he’s been able to thrive in the margins.

“When you became you for a living, which is essentially what happened to me, it encourages you to live a different or better life, or more outgoing life, than I was when I was just a filmmaker, because you always have to come up with some shit to talk about,” Smith says. He’s still the casual, improvisational creator who slapped together Clerks, only now, his professional project isn’t a movie. It’s his existence. “Don’t focus one thing,” he says. “If you focus on one thing, they can get you on that. You’re good or bad at that one thing. If you fancy yourself an artist, just make yourself the fucking art project.”

*A version of this article appears in the September 4, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.