At the time of this writing, Harare, Zimbabwe, is in limbo. There are those who expected the 93-year-old Robert Mugabe would step down in a speech he made on Sunday, and there are those who know the general arc of these things. The power struggle playing out in Zimbabwe is like so many others: brutal and opaque and a little bit clumsy, with moments of massive upheaval punctuating long stretches of mundanity. Tanks roll in unannounced and then they sort of sit there. A speech from a major general from the National Army named Sibusiso Moyo plays on loop on television, This is not a coup. By the time this story is published, Mugabe will have resigned, finally. The options for moving forward are morally gray and the machinations grind slower and slower.

Billy Woods, the New York–based rapper whose 2012 album, History Will Absolve Me, had as its cover a close-up photo of a young Mugabe’s face, understands this as well as anybody. His writing, stretched out over a career that dates back to the turn of the century, is strewn with references to the former Rhodesia: His father was a political refugee of sorts, and left the country in the 1960s, before returning with his family in the early 1980s, after the country gained independence from Britain. At the end of the ’80s, he and his family moved to America; since then he’s lived between here and the D.C. area. None of which is to say that all of Woods’s writing is overtly political — it merely means the power dynamics between a cabdriver and his dispatcher are afforded the proper stakes and context.

Earlier this decade, Woods teamed with another New York rapper, Elucid, to form the duo Armand Hammer. Where Woods is often written about as elusive and enigmatic — he never shows his face in photos — reconstructing Elucid’s back catalogue actually requires much more work. He, too, was putting out music in the early aughts, although many of the records came out as limited releases or were billed under a variety of collaborative names. (Some of his formative works are available on his Bandcamp.)

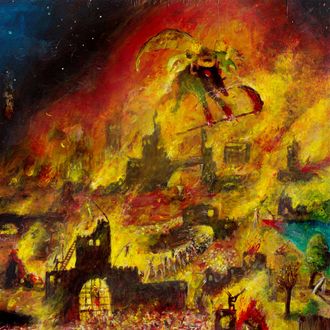

So while both Woods and Elucid had cut their teeth in New York’s notoriously competitive underground circuit for years, it was when they came together, a half-decade ago, to form the duo Armand Hammer that they reemerged as two of the genre’s most vital voices. Rome, their newest record, is also their best, a master class in style and form, and a pointed look at the grand and tiny grasps for power people make every day, from private property seizures to nationalist Facebook rants. It’s a record that fully utilizes each artist’s greatest strengths, and stands up to any rap album released in 2017.

The first Armand Hammer effort was Half Measures, a mixtape released in 2013. Woods, fresh off a return to solo work — the prior year’s History Will Absolve Me, his first album in eight years, was a critical darling — was reinvigorated, and Elucid was plunging into the strangest, most rewarding crevices of his style. That tape was occasionally arresting, but it took until their debut album as a duo, Race Music (also released 2013) for the collaboration to truly distinguish itself from either solo catalogue. That latter record was huge and discursive, with thunderous beats and ponderous dives into the supernatural. It had nearly heartbreaking accounts of an independent musician’s accounting and threaded psychic baggage into back-to-school clothes.

These were not lean times. Over the next few years, Woods released Dour Candy, a full-length collaboration with the veteran underground producer Blockhead; a record called Today, I Wrote Nothing, which has garnered its own cult following of sorts; and a 2017 album, Known Unknowns, which details (among other things) the night two police officers staked out his performance in Montana. There was a brief but super Armand Hammer follow-up, Furtive Movements, in 2014. But the marquee release between Race Music and today was Elucid’s Save Yourself, a sprawling, almost comically ambitious mission statement. Its production (which all comes courtesy of Elucid himself) was daring and experimental, its raps razor-tongued and refined. It’s a record about the seemingly unstoppable forces of religion, gentrification, and decay, and the material and psychological effects they have on us. It’s also about the tension between the accepted narrative arcs we afford those processes and the grim, flat facelessness of it all.

And so, the pair’s latest collaboration, Rome. From the first minute, Elucid’s gut is heavy from bad pad thai; he’s nodding his head to gospel music at a frigid intersection. To use a tired parallel, the album often reads like a great novel — each line is stuffed with such detail that it demands careful attention. It’s dense, but endlessly rewarding: In one verse, less than five minutes into the album, Woods is turning phrases like “streets a yoga mat / warrior pose,” and “pockets got that Bobby Jindal jangle,” and “watching you drop the gun at your baby mother’s house.” A song later, Elucid is interpolating Rae Sremmurd and watching “blue movies on the tablet like I’m non-respectably ratchet.” There are knowing, off-the-cuff comments like, “Words stolen from neighbors in bodegas when I cop my paper / Now you know where I got my flavor.” The work, at times, is taunting you to keep up.

The title isn’t subtle. Rome isn’t either artist’s Big Political Record — all their work is political, overtly and otherwise. There are no songs about Mitch McConnell or arcane Justice Department policy, except in the ways that huge swaths of rap are actually about arcane Justice Department policies. Rome is, above all, Woods and Elucid reveling in the finer points of style, doing acrobatics on the page and in the booth that most of their peers could only imagine in vague terms. There are cogent arguments all over the place (Elucid: “There’s a time and place to not give a fuck / Right now seems so critical / I wanna see everyone who’s been made invisible”) but they often enjamb and overlap. This is not disorganization. It’s a treatise on the country’s present state by way of an endless scroll of granular anxieties. Centuries-old racial animus is couched in irony and bathed in computer light. From “Fanon’s Ghost,” which sounds like a Halloween spiritual: “White supremacist living in squalor, ranting about kikes on the internet / He pressed ‘like’ / ‘Don’t worry, it’s just a meme’ / ‘It’s just a meme’ / ‘My hands are clean.’”

Both Elucid and Woods are superb technicians, although they tend to reveal themselves in different ways: Elucid through a deep understanding of harmony and how to make the guttural sound like song, Woods through a series of off-speed pitches. Rome’s production (Messiah Musik, August Fanon, Fresh Kils, High Priest, Kenny Segal, JPEGMAFIA) pushes and prods each just enough, yanking Elucid back onto a grid long enough to dispense some of his most caustic rhymes and kicking Woods into a more agile gear. And some of the tracks, simply, knock: High Priest’s work on “Shammgod” is a triumphant villain’s theme and Messiah Musik’s opening suite (“Pakistani Brain” and “Dead Money”) is deliriously sinister.

For all its nods to a society that’s burning in ways obvious and small, Rome is consistently and confoundingly funny. On “Tread Lightly,” Woods rears back and cackles at you: “We skimmed through your music, found no reason not to approve it / It was all relatively toothless / You’re just a guy!” and then, even more cuttingly: “Pigs wait patiently for you Negroes to confess / No rush!” On “Shammgod,” the Detroit rapper Denmark Vessey opens with a deadpan “Stepped in the power vacuum, and got my dick sucked”; on “Stole,” Elucid cracks: “Who said God is a DJ? Even they went out of style.”

There’s a sort of bemused grin at the decay that’s creeping up on all of us. On “Stole,” Woods sneers that “Your A&R never shot his way out a parking garage,” but then doubles back: “Now it’s not no A&R / It’s not really nothing at all.” The veneer of order has simply evaporated. The gears that ground down societies for thousands of years rust and air out and keep turning. Mugabe is probably leaving Harare right now, slowly. The album’s penultimate song, “Pergamum,” hears Elucid chasing “new, unexpected patterns with the intention to destabilize language to really get at the core of what’s happening”; it then loops back to the church of his youth, and dissolves into a repeated cry for communion: “Take, eat this, my body.”