As long as there’s been TV, the family has been one of its favorite go-tos. All week long, Vulture is exploring how it’s been represented on our screens.

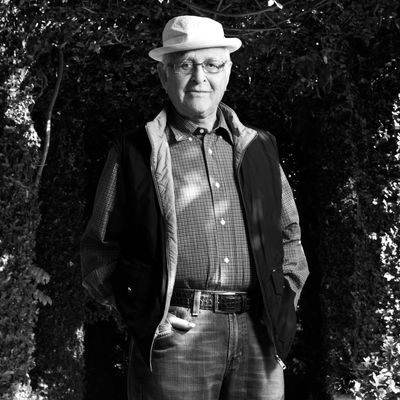

Who better to speak to the importance of family TV shows than Norman Lear, the creator of All in the Family, and one of the most important sitcom creators in TV history? Lear, now 95, realigned the medium back in 1971 when he and his producing partner, Bud Yorkin, created an American version of the politically charged British comedy, Till Death Us Do Part. The result was an unexpected smash hit that spawned multiple spinoffs and spinoffs of spinoffs, including Maude, Good Times, The Jeffersons, and Archie Bunker’s Place, plus the meta-soap Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman and One Day at a Time (the first situation comedy starring a divorced single mother, recently reimagined with a Cuban-American family for a Netflix reboot). We talked to Lear about the importance of family as an organizing unit in television, his experience producing groundbreaking sitcoms during a period when the traditional status quo still ruled, and his feelings on the present and future of the medium he helped shape.

In your career, was it always your desire to work out political issues through family? Was there ever any point where you thought about a substitution, like a school or a police department, that might be better suited for what you wanted to say?

I started off in a family, not a police department. Everything I knew was family, not just my intimate family, but on the holidays, the entire camp. My family used to argue at the top of their lungs and the edge of their throats, constantly. All of the problems of families are the problems we face as a culture — there wasn’t anything in the public culture that wasn’t fodder for family discussion. There wasn’t anything we discussed that wasn’t going on outside of our family, or in some family up the street, down the street, or across the street from each other.

My [producing] partner at the time, Bud Yorkin, was making a picture in London, and he talked to me on the phone one day about a TV show that was a big hit in [Great Britain]. They only did six of them a year, but it was called Till Death Us Do Part, and it was about a bigoted father and his son-in-law. I grew up in a house where my father called me the laziest white kid he ever met, and I would scream at him, “Don’t put down a whole race of people because of one person!” “Ah, that’s not what I’m doing! You’re the dumbest white kid!” So that show was very close to my experience. Hearing about it, I said, “I wonder if there could be an American version?” and Bud said, “We could never do it in America. You won’t get a network to put it on!”

Had you seen a show on American TV prior to that that you felt had that kind of accuracy and honesty to it, a series that dealt with a family in a real way?

No, I guess. The shows up to that point chose not to deal – well, the problems were like if the boss is coming to dinner and the roast is ruined. But that was the extent of the kinds of problems they faced on comedies. It was less problems in the culture generally.

How did you feel about those sorts of shows?

They seemed so odd to me. They were dealing with problems that were discussed in the schoolyard.

Why was it that it was so hard to discuss politics or anything else in an honest way on sitcoms prior to the 1970s, the decade when you had such a great run?

It was H.L. Mencken who said something along the lines of, “No one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American public.” I think that’s what the Establishment believed. It wasn’t what I understood from, at that time, my relatively young life. I’m a serious mind. I understand something about the foolishness of the human condition, but I’m serious. I see the humans at the end of the telescope, focusing on the real.

What was the reaction of the network executives when you showed them the first pilot that you did for All in the Family?

At first I made it for ABC in 1968, and we changed the script because I thought I was revealing 360 degrees of Archie, which was my intention. So I made it three times — twice for ABC because their deal called for me to make it in a year again, and it was still with Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton in their roles, but there were two different young people. They looked at it twice, laughed twice … and didn’t put it on because they were just nervous about it. And then a year or two later, I had already gone out and made a film called Cold Turkey, and Bob Wood, a new person, came in to CBS. They had Petticoat Junction and Beverly Hillbillies and he wanted to change the nature of their comedies. He called me and said, “I want to do All in the Family.”

To what extent were the actors, the writers, the directors allowed to bring their own experiences into the episodes?

In everything I’ve done, everyone involved in the production understood that they had to pay attention to their kids, mates, and whatever was going on in the family. They also had to read the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal, which were always available in our office. And they had to know what families were going through. I can’t think of a single writer on my shows that wasn’t married or had children. They all seemed to have families. The pool we drew from was the national culture.

What was the first incident where the network expressed concern about something you wanted to do?

For our second show, the network didn’t want Archie to write a letter to President Nixon.

I remember that. A classic episode. He put a suit and tie on.

Yes, in order to write the letter! I loved that. Well, the network didn’t want us to do anything topical because they controlled the downside, the reruns, and they thought nobody would want to see reruns that were talking about things that took place four or five years ago.

My point of view was, “Funny is funny is funny is funny.” That’s why Shakespeare works still, hundreds of years later. It doesn’t matter that we don’t get all the references in Shakespeare. Whenever something is good, or funny, or great, it doesn’t matter what time it came from. So we won that battle, and we were topical starting with that second show. We couldn’t be more topical than having Archie write the president. And the subject of his letter was guns!

I don’t know if you’ve looked at All in the Family clips on YouTube recently, but I have, and one of the things I was disturbed by is how many people put up clips of Archie Bunker saying extremely offensive or reactionary things, but approvingly, just completely missing the implied criticism of those sentiments. Did you have a problem with that when the show was in its original run — people not getting that you were criticizing the reactionary mentality?

Interestingly enough, in my experience I never got a letter from someone saying, “Right on, Archie! He couldn’t be more correct!” that didn’t also say at the end, “Go back to wherever you came from, you bastard.” In other words, the ones who were saying, “Right on, Archie!” understood the point of view of the show.

So it’s not like they weren’t getting it?

No, they indicated in every case that they got it. They didn’t go with it, but they got it.

That makes me a little sad, because it makes me worry that people maybe don’t get it as much when it comes to looking at the show now. Or maybe people just love to take things out of context?

Well, look what just happened! The president talked about “shithole” countries, and you have to learn what percentage of America agrees with him.

Do you think Archie would have voted for Trump?

I haven’t thought about it. Archie would’ve gone to the polls [in a story line] that had him firm of mind, but not going to tell anybody. We would never know. Based on what you thought of him, you could think what you wish.

Was there anything politically that the network said you couldn’t touch?

They never said to me, “We don’t want you to do that for political reasons,” no.

So you had carte blanche when it came to subject matter?

No, we argued with the network all the time. There was a great, great guy who ran programming practices, the euphemism for censorship at the time. We had a great relationship. When I did the abortion shows on Maude, he couldn’t believe I was taking on the subject. We spent time together because he came to California and we talked about it, and we wrote in a friend of Maude’s who had four kids that she couldn’t afford, and she was pregnant and would hate to abort the kid more than anything. That was part of the two-episode arc. We had that kind of collaboration, and we did it.

You tried to make a follow-up to All in the Family, 704 Hauser. Why didn’t that one work out?

Because I started too fast. I started out running, and I should’ve started out walking, then trotted, then run. By that I mean, the main character was an African-American dad who was raising a son in the image of Justice Thurgood Marshall. He had hoped the kid would grow up to be Marshall, but he was growing up to be like Justice Clarence Thomas, and he had a Jewish girlfriend. In the very first show, they were sitting on a couch and they were kissing. Now, I would have brought that last part in a lot more slowly had I been sensible, and introduced the little bit that I knew would raise some nerves — nerves that needed to be raised, obviously, or we wouldn’t have done it.

So yeah, we knew exactly what was happening in our culture, and we needed to show it, but it was a case of running before we could even get started. I’ve done that with shows a couple of times.

You’ve had a lot of significant TV shows on the air, and just in the ’70s alone you had All in the Family, Maude, The Jeffersons, Good Times — a spinoff of a spinoff, that doesn’t happen every day — and One Day at a Time …

And Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman. Don’t forget that one! There were a number of them that were only on for six or eight episodes and didn’t work, but Mary Hartman was on five nights a week, all followed by Fernwood Tonight. And All That Glitters, the soap opera, was terrific.

My mother forbade me to watch Mary Hartman because it was too adult and I finally convinced her to let me watch it and I found it so disturbing that I didn’t watch it again until I was much older.

Is that right? What about it disturbed you?

It was something about the tone of it. I think I expected it to be more like your other comedies.

Yeah, well, there was no studio audience. It was just made like a film.

I wanted to ask you about the original One Day at a Time and the new, Netflix version. That, to me, was always sort of an outlier in relation to your other big sitcoms, because all those other shows were — I guess you could say they were part of the Norman Lear Expanded Universe. They were all connected — spinoffs, or spinoffs of spinoffs, with characters from one show going off and getting their own show, and spawning another show out of that, and so on. But One Day was its own separate thing. Where did that particular show come from?

Well, the concept came from Alan Manings, who was working for us as the head writer … the idea for it came from him and his wife, Whitney Blake. They’ve both died now. She was an actress, and they had the idea together because they lived it. She was a mother with two kids and they married eventually, but raising two kids after a divorce — by the way, this was the first divorced woman on TV, and the network made a big thing of that.

Why, when the time came to do a new version of One Day did you decide to make them Latino?

It was a young chap who works with me, Brent Miller. One day, the subject came up of there not being enough Latino families on TV, and he came back and asked me, “What do you think of One Day at a Time with a Latina heading up the family?” and I said, “I love the idea,” so I called Rita Moreno.

What’s the greatest family TV show, in your estimation, that’s not one of yours?

I love Modern Family.

You’re a Modern Family fan! I wouldn’t have guessed that.

Yes, I think it’s very well done. And South Park is basically a family show. It’s all about families.

You like South Park?

I love South Park.

Those guys are kind of libertarian anarchists with some reactionary tendencies. Politically, it’s diametrically opposed to what you believe.

It’s doing what All in the Family did in the sense that it’s letting characters express these inappropriate thoughts that people can then argue about. I mean, it has Cartman, a little character who does the same thing Archie Bunker did. And they even said on 60 Minutes, Matt and Trey, that their inspiration for the Cartman character was Archie.

Do you believe that families on TV reflect what America’s values are at any given time?

I don’t watch enough TV to feel equipped to answer that question. When I say I love Modern Family, it doesn’t mean I watch every single episode. I’ve seen enough to know it’s terrific, but it isn’t like I’m there every week. For anything!

Do you think that TV is more amenable to the kinds of shows you like to make today than it was when you were starting out in the sitcom format 50 years ago?

What I hear from people who are much more involved is “No, not more amenable,” although I’m very happy that NBC wants to work with me on Guess Who Died, the show I want to do that’s set in a retirement village, because we will be dealing with what’s going on in our culture and what’s going on especially with older people. We just did a pilot for that.

That could fall under the heading of an unaddressed taboo: age and mortality. And a community like that nearly always becomes a sort of makeshift family, so it also falls under the heading of “the kind of thing we expect Norman Lear to do.”

Yep. I wrote Guess Who Died in 2010. The script went to everybody who was available to put on a show in 2010, and they all thought it was funny, but to a person, and to a network, they said, “It’s not our demographic,” over and over again. That’s what I kept hearing. Well, suddenly they changed their minds, maybe because seniors are the fastest-growing demographic with the most expendable income, and age is catching up with all of us.