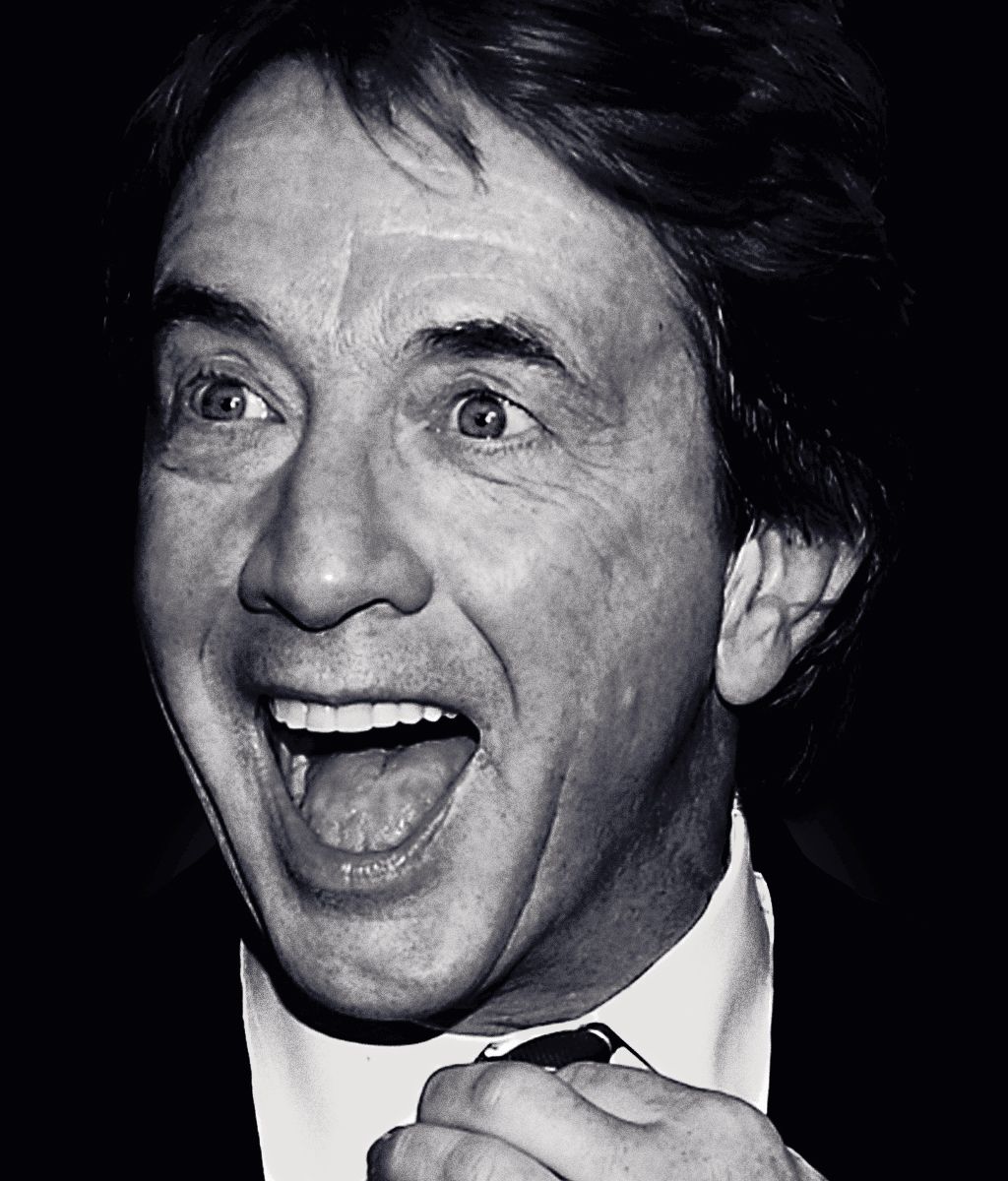

It’s testament to Martin Short’s talent that he’s attained pantheon status in the comedy world while never quite solely carrying one thing — a blockbuster movie or hit sitcom or live special — that was a true mainstream success. (The Saturday Night Live and SCTV alum has joked that his epitaph will read “Almost.”) But chatting over coffee on the front porch of his rambling, cozy home — it’s just west of Los Angeles, nestled between the Pacific Ocean and Santa Monica Mountains — Short talks about his life and career less as a series of wins and losses and more as simply a (very funny) flow of experiences. “You learn quickly,” says the famously affable 67-year-old, who’s frequently on tour with his old friend Steve Martin, “that since you can’t always control the end result of the work, the thing that matters most is having a good hang.” And that he’s mastered.

There’s a bunch of comedians from your generation — friends of yours like Steve Martin or Dan Aykroyd or David Letterman — who seemed to become less interested in, and maybe even cynical about, show business as their careers went on. But you’re still so game for the whole song and dance. What accounts for that?

I don’t think what you’re saying is true. Definitely not about Steve.

You don’t think so? He almost never does movies anymore. You never see him on TV. I think he’s done stand-up once in the last 35 years.

Steve may have soured on stand-up, but not on Hollywood. If Steve comes out here, he’ll have a dinner party and it’s filled with people from the business. But as far as my lacking any cynicism, you have to understand that I grew up in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. If I had been a kid in New York, my parents might have said, “Have Marty audition for whatever is playing downtown.” That’s not happening when you grow up in Hamilton. Show business was something that happened on another planet. But once I realized I could make a living by playing around with hilarious people and get cash handed to me — I never got over that.

When you put it that way, show business sounds pretty good.

I enjoy the work. I’ve always thought one of the tricks of being an actor for a long time is keeping yourself interested once you’ve figured out how to pay the rent. When you get to a point where you’re successful enough that you can say, “I don’t have to take any job anymore,” and you’re still good at what you do, how do you decide what work to take on? I think the answer is that you pursue what you enjoy. In my case, it’s variety. Now, I remember when I … this is getting to be a long answer, David.

No, no. Keep going.

All right, so what I was saying is that I remember when I did the Vanity Fair article, the writer, David Kamp, and I went to dinner. We were off the record at that point. He might remember this differently, but let’s say my memory is accurate. He said something to me to the effect of “Isn’t it odd to have become what you satirize?”

Meaning what?

In the specials I did, I would always satirize the idea of an obnoxious, self-absorbed Hollywood star.

Like with Jackie Rogers Jr.?

Right. And David Kamp brought up Larry David as another example of someone who’s become the kind of success that he used to target in his comedy. So the next day I phoned Larry up and told him what David had said and Larry went, “Is that guy out of his fucking mind?” Larry David feels no different about what he’s doing now than he did in 1984. He still wakes up every morning saying, “I wonder how I can prevent this project from failing.” And I never think, I’m Martin Short and I’ve had success in the past and because of that I don’t have to work so hard. What’s going through my brain is the same thing as 40 years ago.

And what’s that?

That what I’m doing probably isn’t going to work.

When I think of your characters like Jackie Rogers Jr. or Jiminy Glick, they have an irreverence that isn’t super common in contemporary comedy. Are you seeing any younger comedians out there who share your sensibility?

I don’t know if it’s a sensibility. I don’t analyze what I do. The people I work well with — Steve is an example — it’s because we work in the same way. Steve and I will walk offstage, sweat on our faces, the crowd still cheering, and we’ll be discussing, “If we change that one line …” We’re both fascinated by the process of whittling away at the sculpture. Although, it is accurate to say that Steve and I share a comedic sensibility. There’s rarely something that he finds hilarious that I don’t. But that’s also true of me and John Mulaney or Bill Hader — Bill’s as funny as a person can be. And those guys are good guys. If John Mulaney was a prick, I wouldn’t want to work with him, and he wouldn’t be coming over for dinner.

I realize this is a leading question, but how does what you just said square with your relationship with Chevy Chase, who never exactly comes off as cuddly. There’s that story in your memoir about him pegging Mary Hart in the head with a dinner roll.

But that was hysterical.

Didn’t he also leave a shit in your trailer on the set of Three Amigos?

That’s just being a frat boy.

What’s the difference between being a frat boy and being a prick?

Well, Chevy didn’t think he’d actually hit Mary Hart. He was only doing it to make me laugh. When the roll hit her in the head he hid out of embarrassment. I remember the same night, it was at an AFI event, and Charlton Heston — is this in the book?

It is, but retell it; it’s good.

So Charlton Heston stood up to do a speech and he goes, “I guess you could say that I’ve been one lucky guy.” And Chevy goes, “I’ll say!” And everyone was looking around to see who’d said that. That’s the kind of thing Chevy would do. Could it be interpreted as pricky? Sure, but that would be a misinterpretation.

“Nice” is not a common label for a comedian, but you’re often spoken of as one of comedy’s nicest people. Is that at all irritating?

Nice is not a common label for comedians but it is for Canadians. I like it. My father would say, “Marty, do the decent thing.” So if you go backstage and say hello to an actor you’ve just seen in a play, do you say, “That was fantastic” even if you didn’t think it was? Yeah, I think you do.

That’s not a purely hypothetical example is it?

[Laughs.] I had an actress say to me once — about another actress who was in a play with me — “I don’t know what to say to her about her performance because I can’t lie.” And I wanted to say, “Why don’t you do what we did about your last four films and pretend to like it?”

But instead you told a humane lie?

It’s what decent human beings do! I don’t know — I have empathy for people in show business who have zero talent. It must be horrifying for them. But when you can feel that you have legitimacy, it takes away a lot of fear and reduces one’s tendency to be a prick. For example, when I make a movie, I can’t assume that it’s going to work out well. The odds are probably that it won’t. You can do 12 great takes, but if the director is no good, he’ll end up picking the wrong one. But if you know you’ve skillfully done those 12 different takes, you can go home, say, “I gave them slow, fast, big, small, subtle — everything they needed,” and then you can toast yourself with some Champagne.

There’s a Dave Foley quote about Jiminy Glick, where he says, I’m paraphrasing, that Jiminy allows you to express your inner meanness. Is there any truth to that?

The reality is that Jiminy Glick isn’t mean — he’s a moron. When Jiminy says to Mel Brooks, “What’s your big beef with the Nazis?” he’s not trying to put Mel down. He’s just stupid.

So it’s not cathartic for you to play a self-absorbed asshole?

No. I don’t have things festering inside me. I let things out. As a friend, I tend to be very confrontational. If I’m upset at someone, I phone them up and say, “I need to understand this.” I don’t sit on it. Sitting on things is what leads to misinterpretations.

How would a Jiminy Glick interview with President Trump go?

Probably badly. To be quite honest, I wouldn’t do it even if I had the chance. I have such disdain for Trump, and I think his skin is very thin. I met President [George W.] Bush at the Kennedy Center Honors — I guess it was 2007 or something. I did not agree with much of what Bush did politically, but when he walked through the doors, I still thought, Wow, that’s the president of the United States. But I couldn’t care less about meeting Donald Trump. He’s reduced the aura around that office to such a degree that to participate in something that puts a focus on him on any level is something I wouldn’t do.

I was watching an interview you did a few months back with Kevin Nealon, and he described you as someone who performs as though you have something to prove. But then Kevin said that you just brushed it off with a one-liner — “What’s that about, doctor?” — and moved on. Really, though: What’s that about, doctor?

I mean, Steve Martin plays the banjo: So, what’s that about, doctor? You do what you do. I’m there to entertain the folk, and I don’t know how to do it any other way.

But there’s an intensity to your comedy — like when you’re a guest on a talk show — that feels so driven. It even reminds me a little of how Robin Williams’s comedy could feel compulsive.

This is reminding me of when I was a guest on Dennis Miller’s show on HBO — back when I was doing Primetime Glick. We were standing in the wings as Dennis was about to do his monologue and he said something to me like, “Can you believe it? In a half-hour we’re done.” And I said, “In a half-hour I’d still be putting on my first layer of Glick makeup.” How do you explain why my approach to a talk show took 16 hours a day and his was done in a half-hour? I think it’s just because I don’t know how to do what Dennis could do.

So you’d say there’s no psychological explanation that accounts for the way you do what you do?

No. Zero. My style is not remotely psychological. When I first became known, people would interview me and they would’ve found out, “Ooh, his brother and parents died when he was young. Okay, his comedy comes out of his pain.” That interpretation makes sense. I get it. It just isn’t the case. I was putting together that variety show up in my family’s attic before any pain happened. Look, I have no problem with being psychoanalyzed, but I can also tell you honestly that I’ve never been motivated by the admiration of strangers. I’m not trying to make anyone love me. If I bomb, I don’t look in the mirror that night and say, “I don’t know who I am anymore!”

I don’t know how you get through your days without the comfort of a crippling insecurity to lean on.

Neither do I!

I was talking to a friend of mine about you and in sort of a casually dismissive way —

I hate this guy already. You, I like. But this guy I hate.

He said, “Martin Short is always on.” And he was suggesting that there was something inherently insincere about that quality. Do you understand skepticism about a performer who is seemingly always “on” in a high-energy way?

Your friend’s comment is a comment from someone who doesn’t understand show business. When you see me, you’re seeing me in a situation where I’m there to entertain. If you catch me energized and doing jokes with Johnny Carson and assume that’s also what I’m like at two in the morning — it’s like saying, “Boy, I bet that surgeon’s got a scalpel in his hand 24/7.”

When you’re out in the world, do strangers expect you to be funny?

If they do, I don’t care. I was going through an airport once and this woman came up. I had three kids — a 5-year-old, a 3-year-old, and a baby in my arms. My wife was in New York and we were flying there from Toronto. This woman comes up with six pieces of paper: “Can you sign these?” And I said, “No, I’m sorry. I can’t.” As I walked away she said, “And I heard you were nice.”

I bet that story’s grown in the retelling.

“Martin Short? He’s an asshole. He slugged me in the face at an airport.” But again, I don’t have a need for strangers to like me. I’m comfortable with who I am.

How much of a comedian’s fundamental style is innate? There are parts of your book where you write about jokes you were making as a child, and they were the same kind of jokes you’d make now.

I have a slightly copycat personality, which means that I think I do change. Here’s an example for you: When I was in Second City in Toronto, I’d be onstage with Catherine O’Hara. I was so fascinated by her genius that I ended up copying things she did. I can remember, years later, looking at playbacks for one of my specials and thinking, Oh, I’m doing Catherine. She’d do this character Lola Heatherton. She’d go, “It’s 1960 … I don’t even know what year it is. All I know is I’m alone.” And then she’d give this look that I know I give, too. It’s very odd thinking about all this.

What’s odd about it?

The odd thing is being my age but having no infirmity and not being bald and not being obese. I can look at a picture of me in a medium shot from 1990 and say, “That’s the same guy.” In my stage shows I’m still running around like a monkey. I can still do all the things I’ve always done. I think that’s part of why the comedy world I live in is still as fascinating to me as it’s always been.

When you were doing Second City, like you mentioned, pretty near the beginning of your career, I know you’d record your improvisations. How was that helpful?

Catherine O’Hara back then asked me the same thing and my answer was, “Because I’m behind.” Second City came to Toronto in the spring of 1973. I was living there with Gilda Radner at the time. Gilda and Eugene [Levy] and Danny Aykroyd and I were all friends and they were all going to audition for Second City. The assumption was that I would audition too, but I’d say, “Nah, it’s not for me.” I thought of myself as an actor or a singer. Ultimately, I was just afraid. But through the intervening years I’d be partying with the director of Second City, Sheldon Patinkin, or Del Close, and they’d say, “Why aren’t you in Second City?” I knew I’d made a mistake not doing it. So in 1977 I phoned up Andrew Alexander, the owner of Second City and said, “I want to come in.” So he fires somebody and puts me in the show. But I felt I was four years behind everyone else in my development and had to catch up. So while other people were going out for drinks I’d be transcribing the improvisations we’d taped. And that’s because I was treating the improvisations from a writer’s perspective. I was refining what we’d come up with onstage.

Ah, so going over the improvisations became a way to develop material?

Yeah. Nichols and May are the perfect example of that style of working. They are the freaks of improv to me because you can put on their Broadway album from 1960 and it’s as current a comedic approach as you can have. It’s all characters, no jokes, and it’s driven by attitude and satiric observation. If you hear them from their Broadway album and then you see them do a piece on Jack Paar’s Friday night show, it’s the same basic text, but what had started off in improv had been refined through writing and repetition.

What’s the funniest improvised line you’ve ever heard?

I don’t think I have one … But Steve [Martin] can be really quick. One time he said to me, “What’s the worst job you’ve ever had?” I said, “I did a bad pilot in 1980.” He said, “I didn’t say the worst sex, I said the worst job.” Steve also has a story about the fastest ad-lib he’d ever experienced, and it was from Russell Brand. Steve was at the Oscars, and he was leaving right as Russell was getting there. Steve said to him, “Oh, I’d love to meet you, but I’m leaving as you’re coming in.” And Russell said, “It’s a metaphor.”

Not bad!

Yeah, Steve was fascinated with Russell Brand. He’s a fan of everybody. He’s not one of those guys who stops liking new things. You always feel that about Woody Allen. “Who’s your favorite comedian?” “Groucho Marx.” “Hmm. Why is that, Woody? Because he’s not in competition with you?” Steve’s not like that all.

You know, to me the Steve Martin album Let’s Get Small is the perfect crystallization of his comedy. What’s the movie or show or special of yours that performs that function? What is apex Martin Short?

You can never get anything perfect, but there’s a special I did in 1995 called The Show Formerly Known As the Martin Short Show. It’s a moment where I could go, “That’s probably as good as I’ll get.” There was no live audience, so we could edit and trim and figure everything out fully, and the concepts were great. Actually, the smartest thing I did in that special is that I totally shared it with Jan Hooks. That work she does in that — you can’t believe how good she is.

I think there’s an argument to be made that she’s the best sketch comedy actress ever.

God, it’s true. Tina Fey will tell you the same thing. In that special, she does Faye Dunaway, she does David Letterman’s mother, she does Brett Butler to my Tim Burton. She was so, so good.

Valri Bromfield is another name I see pop up as an example of a performer who maybe never got the credit her talent deserved.

Valri I knew very well. She was so funny. I can tell you the day I met her: June 28 in 1972. It was Gilda’s birthday and there was a big party at Global Village, which was this hip theater venue in Toronto where we rehearsed Godspell. Valri and Danny [Aykroyd] were there in character the whole time pretending to be Gilda’s parents. I even remember once driving Gilda’s Volvo — she was in the front and Valri and Danny were in the back, and they were so funny that I deliberately got lost because I didn’t want to have to drop them off. I was 22 and I’d never met people funnier.

But thinking about someone like Jan Hooks, I wonder if there’s a parallel between her career and yours. She never found the perfect vehicle to make her an even bigger star and for all your success, you’re sometimes thought of in a similar way.

Finding a perfect vehicle is what it’s all about. If you want to last in show business you have to have talent, you have to have endurance, and you have to have luck. As talented as Gilda and John Belushi and Danny and all those guys were, if they didn’t have SNL they might’ve ended up in some cheeseball sitcom and we’d never have been aware of their genius.

What about you though? Aside from that one-off special with Jan, have you had enough opportunities to show the full range of what you can do? And I’m not counting Letterman appearances.

I don’t know. It’s in the eye of the beholder. If I said to you right now, “No, I haven’t had the perfect vehicle,” someone who loved Clifford might say, “What is he talking about?” Someone else might say, “Oh, I hate that movie.” So I don’t know what the perfect vehicle is. I do think I was good in Innerspace. But I must admit, I’m very in the moment of doing the work. I don’t dwell on the outcome. I don’t go back and say, “It’s Monday, time to watch Three Amigos!” You also kind of let people tell you what they think. Certain films grow in time. Clifford is a perfect example. I was telling a story about Clifford onstage with Steve and he said, “You see, the people who applaud remember that movie, and the people who didn’t applaud also remember that movie.” When it came out in 1994, Clifford was perceived as too absurdist, and then it became this cult thing that people get stoned to in college.

Speaking of which, I’ve been wondering since college how, logistically, you filmed the movie to make you look child-size the whole time?

[Laughs.] Clifford was total absurdity. My outfit would have bigger buttons to make me look smaller. Or if I was walking around with [Charles] Grodin, I’d be in a trench and then we’d cut to a longer shot and it’d be a 10-year-old walking with him. We had a big party scene and every girl or guy had to be six-foot-four. It was all done like that.

Figuring that stuff out sounds like such a fun game.

Oh, it was great. You’re actually getting at something that’s shaped my career: I’ve always wanted to do the interesting thing, and being in a sustained hit isn’t always the interesting thing. In Canada, where I primarily worked from ’72 to ’79, there was no star system. Being an actor was like being at university. Instead of doing Cheers or whatever for a decade, you’d do 15 different jobs in a year. You’d do Shakespeare for CBC radio during the day, Second City at night, commercials, maybe a CBC television drama. That’s how I’ve continued. If I’m looking back at a year and I can say, “Gee, I was in a movie, I did a Broadway show, I did something on television, I did a great Letterman,” then I’m happy.

If you were guaranteed a green light, what project would you start working on tomorrow?

I’m very aware that if I haven’t done something at this point in my career, there’s probably a reason I haven’t done it.

There must be something.

I don’t think I have an answer.

Come on, what is it? King Lear?

The Trojan Women actually. Okay, there is something I’d kill to do, because I love to sing.

A standards album?

That’s right, actually. Or an evening of singing at [Manhattan’s] Town Hall. If I could look into a crystal ball and know that, You’re going to commit to that and you’re going to do it and it’s going to be a massive hit — then that would be cool. But I believe the audience makes a deal with you: If I’m going to sing a sincere song on Letterman then there better be a sandbag about to hit me in the head.

So your logic is that if you did a night of straight singing, the audience would be waiting the whole show for the laugh to come? For the sandbag to fall?

Yeah. Now, Paul Shaffer is always saying to me, “You’re not allowing yourself to be all of who you are.” But I don’t agree. Also, a lot of people can sing. It’s a unique honor to make people laugh.

How did you used to prepare for a Letterman appearance? To nerds like me who care about this sort of thing, you’re considered one of the truly great talk-show guests.

What I do for a typical talk-show appearance, and I’m not exaggerating, is I’ll send in something like 18 pages ahead of time.

And those pages consist of what?

They could start with an idea for an opening and then it could go to “This story could work, and that story, and that story, and that story, and that story, and that story.” Then we whittle it down. I’ll probably be on the phone with the segment producer for at least an hour-and-a-half going through ideas for material. Then you have to balance all that during the appearance by making it look improvised in the moment, not speaking too much, trying to find common ground with the host. Like if I’m doing Fallon’s show, I’ll make sure we talk about SNL for a bit.

Have you always prepared so intensely?

The first American talk show I did was December of ’82, and it was Letterman. I remember thinking, I’ve got to come across as loose as I can be at a dinner party. So an impersonation of myself being relaxed was the approach from the beginning.

That almost sounds like an oxymoron.

Whether it’s me or Steve Martin or Billy Crystal, the hosts love it when we’re on — remember, they’re doing the show every day — because it means they don’t have to do as much work. Here’s a story: I was on Conan O’Brien’s old show, and I’d done my segment and the next guest, a young actress, came out. I moved down the couch but I was in still in Conan’s eye line. So she’s sitting there and he says to her, “You’re a model, but now you’re acting, so you have to learn these lines. That must be very rewarding.” And I went like this [makes a mock interested face] as she was answering. Conan saw me and went like this [stifles laughter]. Then they go to commercial break and he walked over to me and said, “I’m trying to make a living, asshole.”

You mentioned Saturday Night Live a minute ago. There were obvious practical and aesthetic differences between SNL and SCTV but could you talk about the differences between those two shows as workplaces? SNL is always made out to be this pressure-cooker madhouse, and whenever I read reminiscences from people who were on SCTV it sounds like the vibe was so supportive and warm. How much of that difference had to do with the personalities of the cast?

It wasn’t that. The pressure of the SNL weekly format was a lot for me, which is why I only did the show for a year. But different people have different stories about their experience there. When I signed up in 1984, I may as well been named crown prince. Everyone at SNL worshipped SCTV. I went to SNL with a one-year contract, as did Billy Crystal, Christopher Guest, and Harry Shearer — Harry and Chris were red hot because Spinal Tap had opened earlier that year. The four of us were treated fantastically. If we wrote something, it almost always got on the show, and always in the first half-hour. I’d be in about two scenes a week — always want ’em leaving more was my philosophy — and I’d be done by 12:05.

Did the rest of the cast resent you guys?

There were definitely two divisions. The one-year-contract people were getting a lot of favoritism, but they were also creating good work. Look, the other cast members were Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Jim Belushi — all these talented people. But no one could argue that Ed Grimley hadn’t done well, you know?

What to your mind is the representative SCTV sketch?

There’s a piece from 1978: John Candy was Yellowbelly, the biggest coward in the West. You can find it on YouTube. That could never be on SNL. On SNL, the live audience is there judging you. If something doesn’t get a laugh in dress rehearsal, it’s really hard for Lorne [Michaels] to put it on. But on SCTV, because it was all filmed ahead of time, we could pursue all our odd ideas without being judged. We could just let something like Yellowbelly fly.

This is a total dork SNL question, but in the Jackie Rogers Jr.’s $100,000 Jackpot Wad sketch, who came up with Christopher Guest’s “chocolate babies” line? Something about it almost makes it come off like a non sequitur.

[Laughs.] The week that sketch aired, we had two guest writers: Paul Flaherty and Dick Blasucci, who were two of the main writers from SCTV. We were writing Jackpot Wad, but we knew that if we were involving Chris Guest, you had to get him in a room and turn on the tape recorders because nothing we could write was as funny as what he’d instinctively say. So I believe that line was him. It sounds like pure improvisational Chris Guest.

But that sketch wouldn’t fly today. At least not how it aired in 1984, with Christopher Guest as Rajeev Vindaloo and Billy Crystal as Sammy Davis Jr.

I don’t know if Lorne could have Gilda play Roseanne Roseannadanna today. I’m sure people on social media would complain. It’s ridiculous.

I know what you’re saying, but Billy Crystal not being able to do blackface anymore doesn’t strike me as a huge loss.

But where do you draw the line? Actors should be able to float and zoom and drift into the next persona without fear of “Oh, you’re taking away somebody’s livelihood.” What if you said Meryl Streep can only play Americans? Or Marty can’t do Jiminy Glick because he isn’t overweight? Try to imagine Garrett Morris today—

Singing, “I’m going to get me a shotgun and kill all the whiteys I see?”

No, no.

Saying, “Baseball been berry berry good to me?”

No, no, no.

Sorry.

David, it’s okay. Try to imagine Garrett doing News for the Hard of Hearing today. It’s impossible. Lorne [Michaels] couldn’t do it. But what I want to know is, what if he did? There’d be some mean tweets. So what? One of the secrets here is to not be on the internet all the time — you can take a huge weight off yourself. Ana Gasteyer once said to me that she wanted to go to the Betty Ford Clinic to learn how to stop Googling her own name.

Will Lorne Michaels ever retire?

I can’t imagine it. He doesn’t believe in retirement, and by now he knows exactly how to handle the grind of the show. When I was on SNL the read-through with the host was at 11 in the morning. Now, because Lorne doesn’t like to wake up early anymore, it’s around 4:30 in the afternoon. He’s got it figured out. With his experience comes ease.

It’ll be interesting to see how Saturday Night Live evolves when Lorne is gone, because the show will still be here.

Yeah, now who was it? I think it was John Belushi — he and I were talking when I was in the Toronto Second City cast, and he was laughing about how when he left his Second City [in Chicago], he thought, They’re done. And then, of course, the show kept going. Even with SNL, certain cast members leave and people say, “That’s the end of SNL.” Then it becomes, “Wow, who’s this Kate McKinnon?” The ebb and flow is just the way it is.

I apologize for changing subjects so severely, but I can’t help but wonder if this amazing ease you have with who you are is connected to how well you’ve been able to process grief. Your description in your memoir of how you mourned your wife’s passing — I know this is maybe a weird way to put it, but you seemed to deal with her death in such a graceful way.

I don’t know. When I agreed to do the book I had no intention of writing about Nancy’s death beyond just acknowledging that she’d died. But then as I got into the book it felt preposterous to not write about our journey together, even at the end. I didn’t want to feel like her death was something I needed to hide. I wanted to expose what I’ve experienced about grief and loss. I didn’t see how you could write a book about life and not include those things, because as much as we might wish they weren’t, they are a part of life.

Did it take time after she died to find things funny again?

I’m not sure — you didn’t see me on a talk show for a year or so after she died. But I think that I’ve always had — and it probably comes from the childhood experience of having to go back to school after your brother dies or your mother or father dies — the ability to compartmentalize. Maybe you have to become a little bit frozen emotionally for a while after someone you love dies, but you do find comfort in moving back into the normalcy of “this is me being funny.” I’m not saying that you do a set the night you lose a loved one, but I am saying that grieving doesn’t necessarily impede your ability to do the things you’re good at. I guess what you’re trying to find after something like that happens is what “normal” feels like.

Do you ever find it?

A part of you never gets over it, and a part of you does move on. That’s natural.

As far as I can tell you’ve had a remarkably conflict-free career, but is there anybody in show business who has a legitimate gripe with you?

No one who’s said so to my face. Certainly I know there are people that say, “Jesus, I don’t get Martin Short at all. That’s the guy who I see and am like ‘give me the remote.’” But if people aren’t saying that sort of thing, then it means you haven’t really done any original work — a lot of people find Picasso’s paintings hideous, you know.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations.

Annotations by Matt Stieb.

Illustration by Vulture. Photo by Getty Images.

Bromfield later appeared on a few episodes of SCTV, was a producer on Kids in the Hall, and wrote for The Rosie O’Donnell Show. She’s now inactive in show business, with no major credits since the 1990s. The 1971 Stephen Schwartz musical of gospel parables first came to Toronto in 1972, featuring a bunch of future Second City all-stars (Short, Gilda Radner, Eugene Levy) and to-die-for musical talent. Paul Shaffer was the music director, and Howard Shore, who wrote The Lord of the Rings scores, played sax. Not long ago, Short and Paul Shaffer remastered a crude audio recording of the production and sent it to the cast members. A truly bizarre film: In it, Short plays a devilish 10-year-old who terrorizes his uncle, played by Charles Grodin. In his review, Roger Ebert wrote that in a theater of 150 people, “some 148 did not laugh at all.” Still, Clifford enjoys a second life as a cult classic. Short never won the blockbuster accolades of his SNL peers, but he’s carved out a singular career as a show business jack-of-all-trades. In addition to his comedy work, Short has had major successes on Broadway and turned in stellar dramatic work — his role as the paranoid Dr. Rudy in Paul Thomas Anderson’s film adaptation of Pynchon’s Inherent Vice is a beauty. In 1976, the Second City stage show graduated to Canadian television, where comedians like Short, Eugene Levy, Catherine O’Hara, John Candy, and Rick Moranis imagined the daytime TV programming of a fictional town, Melonville. The sketch comedy ran until 1984, though it lives on among comedy nerds. A Second City invention that became Short’s signature character, Grimley, with his hair greased into a tower and pants pulled up to his ribcage, is wowed by quotidian stuff like Wheel of Fortune and playing the triangle. In 1988, Hanna-Barbera adapted the character for a one-season cartoon, The Completely Mental Misadventures of Ed Grimley. Short and Nancy Dolman met in 1972 while performing Godspell; they married in 1980. After Dolman retired from acting in 1985, the pair adopted three children. In 2010, she passed from ovarian cancer at the age of 58. Short’s description of their time together in their memoir is utterly lovely.