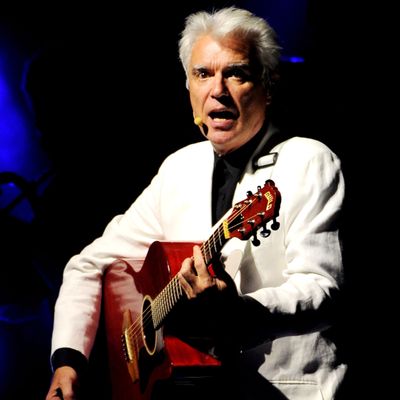

With the band Talking Heads, David Byrne spent the early years of his career using his art to embrace the nonsensical. Now he seems more interested in what constitutes good sense in society. That’s not to say there aren’t some delectably oddball moments on American Utopia, his first solo studio album in 14 years — there are plenty — but that his projects outside of music increasingly provide the context for it. His blogs on everything from Trump to gun control have nailed his personal colors to the mast, and now there’s his lecture series–cum-website, Reasons to Be Cheerful, in which he gathers instances of cities and communities that are experimenting with radical sociopolitical initiatives to great success. For example, when Vancouver decided to treat drug addiction as a health issue, rather than a criminal one, it resulted in fewer overdoses and lower crime rates. As he points out in the lecture, “Everything is connected.”

There are lots of references to money on the record that underline the problematic ways in which it shapes our lives.

Wow, that’s amazing. I realize, yes, I drop those references in there, but hardly anyone else has picked up on that. I don’t write with that kind of intention, I don’t write all “I have to say something about economics” or something like that. But it comes out. Often you realize after you’ve written something, “Ohhh, this is what it’s about. This is what’s really being said here.”

How do you feel about money? Could you imagine a system without it?

I may have called the record American Utopia, but I’m not going to propose a utopia without money or specifics like, “Okay, we’re going to get rid of all money and we’re going to have sex with whoever we want to sleep with.” No, I’m not going to deal with those kind of specifics. But I read a book some months ago called The Moral Economy, and one of the things that writer [Samuel Bowles] pointed out is that people will volunteer to help out in the community, but if you pay them, they won’t. When money enters the equation, they feel like they’re not giving of themselves of their own free will; they’re being bought. I’m kind of paraphrasing this in the worst way, but [what he’s saying] is that people sometimes have good instincts but money can sometimes crowd out their better instincts. That’s not to say it’s not a useful thing, but we might want to be aware when it’s pushing aside some of our better, more generous, altruistic kinds of behaviors.

That’s making me think of the lyrics in “Gasoline and Dirty Sheets”: “I will come down off the stage / The marketplace and the shopping mall / Into the house — the rooms of war / Look at me now and recall.”

That’s me saying I’m going to come and confront you people. I’m going to come into the boardroom, or where you’re making these kind of decisions. You watch out! You will be confronted at some point.

I really enjoyed the Reasons to Be Cheerful lecture on your YouTube channel, which is a confrontation of sorts. Which came first — the album or the lecture series?

About the same time. There was no obvious connection. Sometimes you don’t realize what you are doing is about until you’re getting near the finish. You’re almost done, and then you realize, “Ah!” You get the perspective on it. Anyway, a couple of years ago, before Mr. Trump was elected, I, like a lot of other people, was feeling anger and despair reading the news every day. Just instinctively, I started saving things that seemed vaguely helpful to me. I made rules for myself — to really give me a sense of hope, they had to be things that had been proven to be successful. Not just “someone has a good idea,” the idea had to have been put into effect and tried. I started collecting more and more of them, and I realized I should talk about it. Maybe other people would like to hear about these things I have stumbled on, because they might similarly be feeling frustrated and angry. Not that this is going to totally cheer them up, but maybe a little bit.

I was writing the songs around the same time. [There wasn’t] an obvious connection, but then later on I started to realize that the songs are a kind of macro view of the whole situation, and the Reasons to Be Cheerful stuff in some way responds. It’s not exactly saying everything’s going to be all right, but it’s kind of saying, “Don’t give up yet. Here’s some little tidbits of hope here.”

“Cheerful” is such a quaint, English word — the lecture title is named after the Ian Dury song — and it also, in a weird way, suggests passivity. The lecture seems to be less about making people feel good, however, and more about trying to encourage them to understand their ability to effect change.

Yes, without me saying, “Get off your ass and do things,” there is a sense that these are real things that are going on, real things that people are doing. As much as I love [Dury’s] song, this is [about] more than taking pleasure in a cup of tea and a spliff. This is looking at things that people are doing that don’t demand action from the audience, but they say, “These people have done things, these people are doing things, it’s not impossible.”

What makes you feel like you have a responsibility to spread this knowledge?

I’ve come to think that as citizens — as citizens of the world, whatever — we have these obligations to be a little bit more engaged than we have been. We’ve kind of been sitting back and feeling like, “Oh, I can vote every couple of years, and that’s what I do.” And I think the feeling now is, “Maybe we need to do a little more than that.” Maybe to keep our hopes and our democracy intact, maybe we need to do a little more than pull a lever every couple of years.

Which is easy for me to say. I’m a successful pop musician, and I can’t be saying to people, “Do what I do.” Not everybody is in a position to do what I do. But I think everybody has their own way of being engaged.

In the Q&A section of the lecture, someone asked “How do I get involved in the community?” I liked that you said getting involved has to come from a place that makes you feel good, and shouldn’t be coming from a place of guilt or shame.

Yes, that’s not going to be much fun.

Are feelings of guilt or shame things that you have dealt with? There is a wider understanding of white privilege these days, and the responsibility that comes with that. But there’s also “white guilt,” which often leads to performative actions rather than real change. What are your thoughts on that?

It’s complicated. I have to say I probably don’t feel guilty, but I also feel like in order to do the right thing, there’s constant awareness and struggle. It’s necessary.

The song “Doing the Right Thing” feels like a skewering of privilege.

Yes, it’s a bit of a skewering. Most of the songs are not. That one is kind of ironic. You’ve got this very pretty melody that’s kind of scathing. A lot of the words came first before the music. Not totally shaping them into all the verses and choruses, but there was a lot laid down before the music came in. Which would seem to imply that there was something being said rather than just a lot of syllables. [Laughs.]

How did you assemble the group of young collaborators on the record?

A guy named Mattis With, who is partners in a small label called Young Turks, [helped me.] He’s Norwegian, lives in London, and we’d talk occasionally. I didn’t mention the record [at first]. Then at one point I said, “You know, Mattis, I have a record I’ve been working on. Would you like to hear it?” And I played it for him and he really liked it, but he said, “I think you can take it further, and I think I’d like to suggest some other people as collaborators and contributors.” So he was really helpful in that way. There were people I was already aware of, like Sampha and Dev Hynes, who played on something — we’d done things together before. But a lot of the others, I didn’t know — OPN [Oneohtrix Point Never], I didn’t know. He came in, we got along well, so when he said, “I have some tracks that maybe you’d like to see if you can do something with,” I said, “Sure, sure.”

Every generation’s artists have to try and figure out what their musical language is, and how much of the languages of the past they want to recycle or reject. That kind of exploration is very much evident on the album. There’s country and ambient and pop alongside so much more. Do those juxtapositions still thrill you in the same way they did when you were starting out?

Yeah! And I sense a lot of these musicians are approaching the sounds and the musical ideas that they bring in a completely different way than what anything I’d imagine. Which is great.

Different in what kind of way?

There was one section of one song — I forget who did it — and it just sounded completely haywire, like the rhythm just completely fractured, but it worked beautifully. As long as I could keep the singing really smooth as everything was crumbling and crashing beneath, then it all comes back together again. That was not something I would ever come up with myself. That’s why you invite people [to collaborate].

On “Everybody’s Coming to My House,” there’s a part — the “We’re only tourists in this life” section — where it completely clears out and goes to halftime. It didn’t come from me. My demo is still barreling along. So that’s another thing one of the collaborators brought.

You’ve made albums with mostly women before, but I noticed the collaborators on American Utopia are all men?

Yes, I would guess so. It wasn’t intentional. [Note: after this interview, David Byrne released a statement further addressing this issue.]

In the spirit of “everything is connected,” what are your thoughts on toxic masculinity?

There’s obviously a lot of things we can do right now, but it’s also a deep-seated problem. Goes back about 2,000 years, when the patriarchal religions overthrew the matriarchal religions, or the religions that had multiple men and women gods. Okay, where does that come from? Does that come from the rise of city-states and agriculture and the need for that kind of administrative control? I don’t have an answer, but there was a big switch there. As much as people might think [the patriarchy is] intrinsic to our nature, it wasn’t always. Two-thousand years is relatively recent, so who knows what the future might hold? Something different could happen.

I read the cartoon version of Genesis, the book in the bible. It follows it word for word. You realize it’s a sordid tale of a lot of head-bashing and land-grabbing. Nasty stuff. [Author R. Crumb] does it word for word, and he writes his own commentary in the back. A lot of it is very much this: “Wait a minute, this character, when you look back on it, was originally a woman. They changed it from a woman to a man, but they forgot to fix some of the aspects of the story.” In some of the books, there’s this weird disconnect in the story, a little narrative hiccup that doesn’t quite make sense because they switched the gender of some of the people. It’s just like, Hmmm, okay. [Laughs.]

Religion helps institute the patriarchy.

Yes, religion says, “This is the way God wants it to be” — the ultimate justification.

In the liner notes for American Utopia, you highlight that the Europeans who colonized the Americas believed they were reaching for utopia, and yet they are responsible for the genocide of indigenous peoples, and the enslavement of African peoples. History’s definition of utopia often rests on the subjugation of others. How can we find a different route to utopia?

My response would be to look around the world and see if you can find a place where they’ve done it in a more equitable way, where it seems to be succeeding. I don’t know where that might be, but I imagine it might be a little community or it might be a whole country. Start looking: What are they doing? How’s it working for them?

Releasing American Utopia at roughly the same time as Reasons to Be Cheerful feels smart because, like you say, they point to each other. The album can help amplify the conversations raised in the lecture series.

In a way, yes. This gives me something else to talk about, other than writing songs, which sometimes seems a very small thing. Let’s talk about other stuff, too.