In 2005, Curtis Sittenfeld published her first novel, Prep, a snarky Midwesterner’s foray into boarding school, a world quite apart from her own. The book was praised for its incisiveness; its protagonist, Lee Fiora, is something of a modern-day Lizzy Bennett, riffing on rituals that her peers never bothered to question. Sittenfeld probably wouldn’t object to the comparison. In 2016, she wrote a retelling of Pride & Prejudice, for a series of Austen updates.

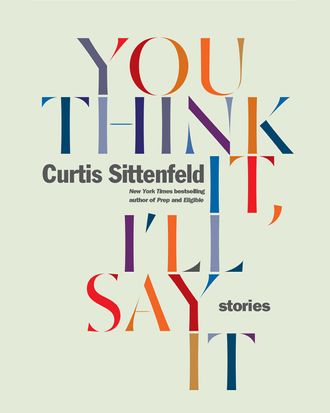

Her latest book, a collection of short stories called You Think It, I’ll Say It*, is marked by the same pointed wit. But often, Sittenfeld’s smartest, most noticing characters are wrong in their judgements, and forced to reckon with life’s complexities, and contradictions. It’s an appropriate arc for the social media era: a tale that cautions against snap judgements. “A character who’s smart but wrong?” Sittenfeld told Vulture. “To me, that’s super interesting.”

You’ve published five novels. Why did you decide to publish a story collection, and why now?

For most of my life — well, maybe half of my life — but basically until I was in my mid-20s, I wrote stories. From the time I was 5 or 6, until I was 25. And I read a lot of stories during that time. But my first book was a novel, and I think that if you publish a book — I guess if you’re lucky you have some momentum, it’s almost like there’s a likelihood that both you and your publisher think you should keep doing the thing you just did. So, I just got on a novel track. Ten or 12 years passed.

Then in 2016, my novel Eligible came out. It was my fifth novel, a modern retelling of Pride and Prejudice. I went on a little book tour. I think I felt wound up from being on book tour, and kind of distractible, and I thought, “I need to calm myself down by writing.” So I wrote this story that I called “Gender Studies,” and I submitted it to The New Yorker. When that story was submitted, and it was accepted, and it ran, I would sit down at my desk and open a new file for a story, and I did this, you know, six times in a row or something, and then lo and behold, I had a collection. All these stories that I had been saving up all these years kind of came pouring out of me. It’s a little bit corny, but almost like meeting up with some friend I hadn’t seen in 12 years, and remembering that the person was just as delightful as I wanted them to be. A couple of the stories are from before the deluge. There was one story that’s from 2015. There’s three from the past, and then seven that I wrote from June 2016 to March 2017.

Two of the stories in your collection dramatize the 2016 election by attaching it to specific characters’ lived experiences of it. Did you begin writing those stories immediately after the election, or did you feel you needed some distance from it?

The answer is different for the two different stories. For “Gender Studies,” I wrote that story in May and June of 2016. People have said to me, “oh, it’s a political allegory,” and I think, “sure.” The political stuff is definitely there. But that’s why I like fiction; there can be lots of different things going on, and it’s all intertwined, and you can’t separate out what’s in what category. But if I was really going to say, “how did this story originate, what’s the premise of it,” I would not say, “a man and a woman with different political views are uncomfortably attracted to each other.” I would say, “a woman loses her driver’s license.”

The story “Do Over” was probably more directly influenced by the election. I wrote it in March-ish 2017. Again, to me I would say that story is about a man and woman who went to boarding school together, who meet up 25 years later, and have different agendas. I wouldn’t say, “it’s a story about people interacting under the Trump presidency.” I never write something and consciously embed political commentary or any other kind of commentary. I just try to get the characters into a room or out of a room, or onto the plane, or through the grocery store. The political stuff, the class stuff, the gender stuff, is in the air, it’s in their interactions, because it’s there for all of us.

I’m interested in “Do Over,” and why you chose the character you chose to follow around. He’s not a Trump voter but he’s at least ambivalent about Hillary. Why were you interested in embodying his perspective?

He seemed to me like a really plausible version of a man who went to boarding school where his dad was a trustee, and now is about 44, 45. I feel like I’ve encountered — well, not tons of men like that — but, you know, some. They’re very polite, but then maybe the more defensive they feel, the less polite they are? And also — I’m the one making a stereotype here — but with that type of person, I have sometimes felt like there can be a narrow version of female behavior that’s acceptable.

They’re having this dinner, so they can’t really hide from each other, and she’s acting in a way that makes him increasingly uncomfortable, or that he finds increasingly distasteful.

It reminds me of certain Mary Gaitskill stories; two people are stuck at dinner, with opposing views on how the other should be behaving. It’s interesting to me that you chose his perspective, not her’s.

It’s funny because [my collection] has two stories from male perspectives, and I’m not sure where they came from. It wasn’t a conscious choice. The one called “Plausible Deniability,” when I started writing it, I thought it would be about a sister. But it ends up being two brothers who go for this morning run. I started writing it thinking that it was told from the younger sister, and then I got a few paragraphs in and I thought, “wait a minute, this is a man, not a woman.”

How did you feel after — or while — embodying the perspectives of these men who are, in some cases, objectifying women?

I should probably be careful admitting this, but sometimes, when my characters are having a disagreement, it’s a disagreement I’m having with myself. I can see both sides of the argument. So, these former boarding-school classmates have this dinner, and she thinks he’s kind of entitled and boring, and he thinks that she’s bad-mannered and more unsavory than she needs to be. I kind of agree and disagree with both of them. But I actually think it makes the fiction better. I don’t like reading fiction where you can so clearly see where the author’s sympathy lies. They’ve made one character charming, and one abhorrent. In life, it’s much more interesting to have ambivalence about a person than to just think they’re detestable.

It seemed to me that several of the stories address misinformation and false judgements. In “The Prairie Wife,” the protagonist sees her past lover on TV and thinks she’s a sellout, but she winds up being wrong.

I think you’re right, that is a sort of theme of the story. It’s just interesting in life that intelligent people can be wrong about a lot of things. Including, and maybe especially, situations and people close to them. In some ways there’s like an underlying theme in the collection of characters thinking, “my god, I’m in my 40s, and I thought I’d have clarity by now, but I actually feel more confused than I did ten years ago.” That’s a real phenomenon. Life is very confusing. I sometimes think that people who think it isn’t are kidding themselves. Human behavior is complicated, and life is complicated, and families are complicated. A character who’s very smart and always right in her judgement is kind of boring. A character who is dumb and wrong about everything is boring in a different way, and is probably condescendingly portrayed by the author. But a character who’s smart but wrong? To me, that’s super interesting.

You’ve returned with a couple of these stories to writing about prep school.

It’s funny, because there is a part of me that’s like, “Ugh, Curtis, don’t you have boarding school out of your system by now? You graduated from boarding school 25 years ago. Give it a rest. Move on.” But then another part of me thinks, well, there’s a few untapped situations that are interesting to delve into.

There are times when I think I might write a Prep sequel. It’s funny because actually my editor of all people discouraged me. She was kind of like, “you might just want to leave Prep alone.” But if I returned to Prep, the main character would not be a current student anymore. It’d be examining some of the same subject matter from a different angle.

You mentioned that you’d never write with an issue like class consciously on the brain. But I was interested in how the prep-school stories consider class, and then it seeps into your stories about motherhood, too. Why do you think motherhood might be a good lens through which to examine something like social class?

That’s an interesting question I’ve never considered. Motherhood — parenthood — is an interesting experience — especially people who have children at older ages. It’s almost like you’re making all these small and large, very deliberate choices, and your own sense of identity and your values get really tangled up in those choices. Most feel mothers feel like the stakes are very high, they want to get things right, but it can manifest itself in ridiculous ways, like feeling like there is only one right way or one best way to do things for your child. It just brings out some kind of animal instincts, and some confusion. Stuff that’s not that great in real life, but it’s great for fiction.

So, the collection is getting adapted into a Apple TV show, executive-produced by Reese Witherspoon, starring Kristen Wiig.

It’s supposed to be — one hopes — a multi-season show.

Are you very involved?

I think I’ll be somewhat involved. The person who is developing it is a woman who will be the showrunner, Colleen McGinnis. She’s worked in developing other stuff of mine for TV, so I know her and really like her, and we communicate. A writer’s room doesn’t exist yet for the show, but when she’s writing stuff she will check in with me and ask me questions about characters. At this point, it’s been pretty informal. I live in the Midwest, and I’m not planning to move to L.A., so I think that I will be involved a little bit, but it’s not like it’s what I’ll do instead of writing fiction.

Are you excited about the casting choice?

I’m delighted. Who wouldn’t be?

*This article originally misstated the title of the book. We regret the error.