Milton William “Bill” Cooper (1943–2001), while largely unknown in the hated mainstream media, was the most important “conspiracy” writer and thinker of his time. Chances are individuals like Alex Jones, QAnon, and even Donald Trump would not have manifested the way they have without the influence of Bill Cooper and his book Behold a Pale Horse, which, 27 years after it was first published in 1991, remains the primer of the new American paranoid canon.

Cooper’s life, from his military service as a riverboat captain in the Vietnam War through intense exploration of the “fringe” culture of UFOs, the Kennedy assassination, the Knights Templar, radical patriot militias, and the 9/11 Truth movement, ended the only way it could have. In November 2001, as he predicted on his shortwave-radio show, “The Hour of the Time,” Cooper was shot dead in a gunfight with police on the doorstep of his hilltop home in eastern Arizona. Long before that, however, the influence of Cooper’s work had extended to unexpected places like Harlem and the New York housing projects that gave birth to hip-hop.

Nowadays you can buy a copy of Behold a Pale Horse from Walmart for $17.34 with two-day shipping. But if you want to know how Bill Cooper’s book came to Harlem, the fastest way is still the A train to 125th Street. From there, walk east to between Frederick Douglass and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevards, which is where, if he’s in the mood, you can find Bro. Nova at his sidewalk table across from the world-famous Apollo Theater.

All varieties of items can be bought from street vendors on 125th Street: vats of sheaf butter, aphrodisiac tinctures, copies of old Bruce Lee and Pam Grier movies, $12 Louis Vuitton pocketbooks made in Shenzhen. But even though he’s spent more than half his life as a 125th Street merchant, Bro. Nova, a tall and sleek man now in what looks to be his early 40s, has always stuck with books.

It is a matter of continuity, Nova said. That was because, no matter how much they gentrify the neighborhood, “In the Beginning, there was the Word, and long after all this shit has been washed to the sea, there will still be the Word.”

Among the most celebrated of Harlem booksellers was Lewis Michaux, who for 40 years ran what he called the “House of Common Sense, Home of Proper Propaganda” at the corner of 125th Street and Seventh Avenue. Michaux’s bookstore claimed to contain nothing less than “the world history on 2,000,000,000 (two billion) Africans and non white peoples.” Hot-selling volumes were touted with ads reading, “The God Dam White Man is the title of this Book. Read it!”

Bro. Nova and his fellow merchants carry on the tradition. On their tables are the classics, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, Toni Morrison, a hard-boiled Donald Goines. Beside these are dog-eared tomes like Yurugu: An African Centered Critique of European Cultural Thought and Behavior, by Marimba Ani, and Are Caucasians Edomites?, by Dr. Malachi Z. York, founder of the Nuwaubian Nation, who is currently serving a 135-year sentence in the Feds’ Florence, Colorado, supermax. It might seem a reach to find Behold a Pale Horse in this company, but Bro. Nova and his friends have done a brisk business with Cooper’s book for decades.

Seventeen years after his demise, Bill Cooper retains considerable name recognition on 125th Street. Mention of him and/or Behold a Pale Horse rang a bell with a surprisingly high number of people of a certain age who identified themselves as longtime Harlem residents.

“Most people, anyone who once thought of themselves as radical in any way, knows William Cooper,” said one dapper-looking man standing under the marquee of the Apollo. “Behold a Pale Horse, we used to just call it ‘The Book.’ ” Others recalled talks given by the late Steve Cokely, an African-American independent researcher–street speaker who occasionally referenced Cooper. In the middle of a presentation on topics like Cointelpro, Cokely would pick up a copy of Behold a Pale Horse and say, “Let’s see what the white boy has to say about this.”

Still one of the most-shoplifted books in Barnes & Noble history, the popularity of Behold a Pale Horse began in prison, places like Attica, Clinton/Dannemora, Green Haven, and Sing Sing, where Cooper’s extreme paranoid view made complete sense. Besides, as Bro. Nova said, “Where else were people going to read it? Back then everyone was in jail. Or dead.”

This had the ring of truth. In 1990 and 1991, 5,077 people were murdered in New York, by far the highest two-year total in city history. It was the crack plague, and a new generation of griots arose to speak truth to the ongoing trauma of urban life. Many of the rappers who emerged during the early 1990s, the great Wu-Tangs, the formidable Nas of the Queensbridge Houses, were deeply influenced by the Five Percenters, a.k.a. the Nation of Gods and Earths. The movement had been founded in the late 1960s by Clarence Edward Smith, a.k.a. Clarence 13X, and eventually “Father Allah.” Kicked out of Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam for heresy and gambling, Father Allah said it was necessary for black men and women to become “lyrical assassins.” The tongue was “the sword,” Father Allah said, and when properly sharpened, it could “take more heads with the word than any army with machine guns could ever do.”

For many lyrical assassins, Bill Cooper’s Behold a Pale Horse became a key text. Rappers who have mentioned Cooper or his book include the Wu-Tang Clan, Big Daddy Kane, Busta Rhymes, Tupac Shakur, Talib Kweli, Nas, Rakim, Poor Righteous Teachers, Gang Starr, Goodie Mob, Suicideboys, Boogiemonsters, Wise Intelligent, Public Enemy, Miz MAF, Aslan, Lord Allah, Ras Kass, and the Lost Children of Babylon, who told their listeners to prepare to meet your fate “like William Cooper … when the storm troopers breach your gate.”

The key to Cooper’s appeal, said Ol’ Dirty Bastard, he of blessed memory and court jester of the Wu-Tang Clan’s early Behold a Pale Horse adapters. “Everybody gets fucked,” ODB told me when we spoke in 2004. “William Cooper tells you who’s fucking you … when you’re someone like me, that’s valuable information.”

One of Cooper’s biggest acolytes was the late Prodigy, who along with Kejuan Muchita, a.k.a. Havoc, made up the classic NYC hip-hop duo Mobb Deep. Once I asked Prodigy if it was true, as he’d said on a rap website, that he had read the 500-page, densely typed Behold a Pale Horse four times. “No. That’s a misquote,” the rapper replied. “I read it six times. I needed to get that shit right and exact before I went out there.

“William Cooper wrote what everyone kind of knew,” Prodigy said. For many in the black community, it was common knowledge that the CIA was bringing dope into the ghetto to further enslave the people. What was the big surprise that, as Cooper claimed, AIDS had been whipped up in a test tube at Fort Detrick (home to MKUltra) as a plan to wipe out Africa? The fact that Cooper was a former naval intelligence officer, a big fat white guy who lived in Arizona, only made it all the more believable.

It was Prodigy who helped bring Cooper’s message of widespread mind control to the larger hip-hop audience. He did it in a single verse, in the 1995 video for the remix of LL Cool J’s “I Shot Ya.” Filmed in dramatic black and white, the rapper stands in an alley and lets out the 411 of the perpetually harassed.

“The Illuminati wants my mind, soul, and my body,” Prodigy rapped. “Secret societies trying to keep their eye on me.” As many hip-hop listeners attest, this was the first time they’d ever heard of the Illuminati, the malign presence allegedly behind so much of what was wrong with the world. After Jay-Z picked up the phrase in his 1996 album Reasonable Doubt, the meme predictably blew up. But, as Prodigy told me, the first place he saw the word Illuminati was in Behold a Pale Horse.

If Prodigy began the first generation of Cooper-influenced rappers, Andrew Kissel, a Newark, New Jersey, MC who performs under the name William Cooper, was the start of the next.

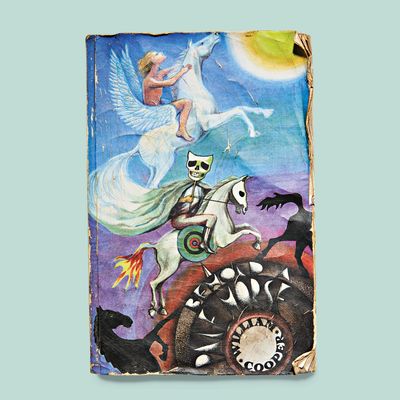

The William Cooper reference kept coming up in Google searches. The first item that jumped out was a YouTube “Cooper” made for his 2009 debut album, Beware of the Pale Horse. Entitled “American Gangsters,” the video begins with a menacing plinking of a child’s music box. Then, set against an image of barbed wire twisted into the pattern of a double helix, the voice of William Cooper arrives with an all-inclusive j’accuse. “The CIA wants my DNA wiped off the planet!

“9/11 terrorism,” the rapper declares. “The secret government planning / Gave birth to the recession / Now the world’s in a panic / Another amber alert got the sheeple running frantic.” Shouting out an RIP to his namesake (“Rest in peace, William Cooper!”), the rapper says he and his crew are on top of the plot, “the puppet masters pulling strings for the microchip future.”

William Cooper turned out to be an interior-lineman-size white guy in his middle 30s, wearing a long yellow T-shirt over knee-length cutoff jeans, who’d been raised in a lower-middle-class family in Bloomfield, New Jersey. Originally he rapped as part of a duo, Booth and Ozwald. “We wanted money, dead presidents; we figured that was the best way to get them,” William Cooper said. It wasn’t until 2005 that Killah Priest, an esteemed member of the Wu-Tang extended family, suggested he change his stage name to William Cooper.

“Priest said, you should be William Cooper,” Kissel recalled. “I didn’t know what he was talking about. I never heard of William Cooper. Priest said, ‘Go to the bookstore, get a copy of Behold a Pale Horse, read it, and come back and tell me if I’m right or wrong.’ ”

Kissel read through Behold a Pale Horse with interest. There was some crazy stuff in there, nutty ideas about UFOs, but a lot of it made sense. Something wasn’t right in the country, people weren’t as free as they thought they were and deserved to be.

So Andrew Kissel told Killah Priest, yeah, okay, he’d be William Cooper. Ten years later, even his mother calls him Cooper. As for Bill Cooper, he’s called “Milton William Cooper” so no one gets mixed up. It was a lot better than naming yourself after some drug dealer like Noreaga or Rick Ross, Kissel thought.

“He was a patriot,” Kissel said of William Cooper. “I like that, because I am a patriot too. I am a proud American. This country was supposed to have been built to question authority, to hold the people in power accountable. Not to bite your tongue.”

A few months later, William Cooper gave a listening party for his new album, God’s Will, at New York’s Quad Studios. It was a famous spot. Tupac got shot there in 1994. The Quad also offers a boffo view of Times Square from its tenth-floor window. On this particular night, the tourist hubbub was interrupted. It was a few nights after Freddie Gray had been killed riding in the back of a Baltimore police van. Protesters were down there, duking it out with the NYPD. Watching the confrontation from above, William Cooper said it was “an omen,” a possible sign of things to come, but unlike his clairvoyant muse, William Cooper was not about to predict what those things might be.

*This article appears in the August 20, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!