Every few months, New York Magazine art critic Jerry Saltz will be filling Vulture in on his favorite art books — biographies, catalogues, coffee-table books. Welcome to the inaugural roundup.

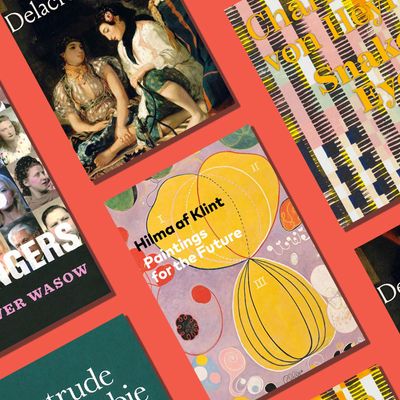

Friends Enemies and Strangers, by Oliver Wasow (Saint Lucy Books)

A few years from now this collection of uncannily intense, haunted, insightful photographs by top-notch photographer-encyclopedist-archivist — and MacArthur-deserving — Oliver Wasow (with two inspired short texts by novelist Rabih Alameddine and artist Matthew Weinstein) will provide a penetrating look at some of the darker characters now on the American political stage. That means the whole odious Trump brood as well as Republican enablers like Paul Ryan, Kellyanne Conway, and Sean Spicer. Each picture seems to have been slightly altered but you never see how; the colors have been pitched toward the eerie, gaudy, and phantasmagorical. Also on hand are a collection of psychologically probing pictures of Wasow’s friends, family, and neighbors. The whole thing is an American yearbook. That it was conjured together via a Kickstarter page also attests to the viability of art in the hands of those outside the purview of the gatekeepers. The book is its own pictorial Guns of August–style summation of a foreboding fragment of time with world-changing repercussions.

Charline von Heyl: Snake Eyes, by various authors (Koenig Books)

This beautifully designed book is devoted to the artistic fireworks and optical accomplishments of German-born New York City resident Charline von Heyl (born in 1960), whom one critic has called “the most exciting American painter right now.” The charismatic intelligence pictured in these ever-changing, highly charged, intensely graphic, and profusely colored paintings may well convince you of that. Von Heyl’s is a restless mind and eye. Her work thrives on continual probings of painting’s every tenet: surface, color, viscosities, composition, form, configurations, ideas of beauty, ugliness and risk-taking. As seen in this dual English-and-German volume, it’s no wonder that von Heyl is admired as an “artist’s artist” — someone infinitely admired by fellow practitioners. She really does bring an incredibly complex set of visual-conceptual talents, techniques, tools, and optically alchemical magic to every painting.

Delacroix, by Sébastien Allard and Come Fabre (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 25)

Here it is, everything you need to know about the ingenious French freak of painterly nature, Eugene Delacroix (1798–1863) — subject this fall of his first-ever comprehensive North American retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum — all in one beautifully illustrated book. If you’re not exactly sure who Delacroix is or why he’s so epically important (I would rate him as indispensable to understanding all of 19th-century painting), this is the book to read. No other museum catalogue text about this master — or many others — is so lucidly written, accessible, and fun to read. It helps that the long essay, written by two Louvre scholars, feels like an impassioned fever dream. Which is a good way to describe Delacroix’s best, often head-spinning, all-over-the-place work. Read this and you will understand how and why Delacroix is the painter who shows the way for his medium to break free from the rigid strictures of perspective that had been in place for centuries, who blows apart the smooth unruffled surfaces that had been the rule for centuries before that, and who liberates the practice from subject matter itself by showing that paint alone, deployed dynamically and originally enough, can carry a picture. This book introduces us to Delacroix the reformer, who delivers painting from illusionism to painting-as-expression, from well-rendered fussy draftsmanship to painting as physically alive — the artist who leads directly to Courbet, Manet, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, van Gogh, and Cézanne.

Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, by Tracey Bashkoff and Tessel M. Bauduin (Guggenheim Museum, October 23)

Place this gorgeous book on top of your coffee table. When people ask you in amazement, “What is this beautiful book?” you can just nonchalantly say, “Oh this? It’s the catalogue for the Guggenheim’s full-scale retrospective of a woman painter you’ve never heard of who invented abstraction before Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian, and the lot of them. Oh, and she is a genius.” This single full-color volume delivers the virtually unknown Swedish visionary genius, born in 1862, who between 1906 and 1915 created 193 large paintings that reach the further shores of abstraction and deliver a complete pictorial syntax of shapes, forms, color, surfaces, and diagrams. The implications of these works are not only gargantuan, but also infinitely pleasurable to look at. And as written about in this wonderful volume, great to read about. By the time you put down this book, Hilma af Klint will be embedded in your visual library forever.

Gertrude Abercrombie, by various authors (Karma Books, October 23)

This thick, lavishly illustrated, perfectly square, beautifully written four-and-a-half-pound catalogue, containing more than 70 images and photographs, makes for a tremendous introduction (or reintroduction) to the almost-forgotten storybook-like paintings of Chicago Surrealist Gertrude Abercrombie (1909–1977), the poignant midwesterner, jazz devotee, bohemian, saloniste, and moving painter. The volume was published to accompany an awe-inspiring show of the artist’s works and single-handedly puts a deserving artist smack in the sights of museum curators everywhere. Let’s hope they take notice. That the book and exhibition were produced by a small gallery and organized by independent curator Dan Nadal only makes all this that much more special.