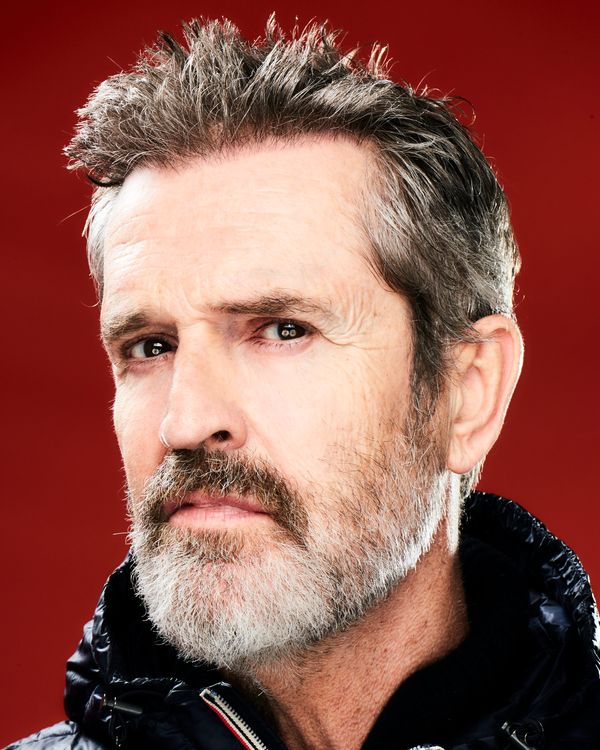

There are passion projects, and then there’s Rupert Everett’s The Happy Prince. Fascinated by Oscar Wilde since childhood, the actor in 2008 announced that he would star in, write, and make his directorial debut helming a film about the literary icon’s final days. All he needed, he said, was the money to make it. What followed was eight years of Everett pressing away at the project, a period that included two stints playing Wilde in revivals of David Hare’s The Judas Kiss, which functioned as something of an unofficial audition.

Production on The Happy Prince finally began in 2016, and now, after playing Sundance in January, the film has opened in the U.S. just in time for biopic season. While making a rare trip across the pond to promote the film, Everett spoke to Vulture about the long process of bringing the project to the screen, his favorite Wilde quotes, and his desire to find a rich patron who will make his next film much easier.

When I was doing research, I found an old story announcing the project where you say, “What I really need now is a billionaire who loves Oscar Wilde and Rupert Everett and who will pay for the whole thing.” Did that happen?

No. I did find some backers, but I didn’t find the billionaire boyfriend who would pay for everything. I’m still looking by the way, because I’m trying to mount another production, a disco romance set in Paris in the 1970s. I’d love to do it through a billionaire.

How do you think this film would have been different had you been able to make it right away?

It’s an interesting question. Those ten years of grind were really useful to me. I hadn’t made a film before, and it enabled me to test my script again and again. I knew my script inside out by the end of those ten years. Also, halfway through the 10 years, I performed in The Judas Kiss, so I had the opportunity of playing Oscar Wilde for a year. That was enormously useful, because I was able to slip into the role without having to worry. In the play, I was able to define the look of Oscar Wilde that I wanted to have: the body and the hair and the teeth. I suppose I’m quite an old-fashioned type of actor; I work from the outside in.

One of the things I liked about the movie is you get this sense of Wilde as a mountain of a man. He’s this gigantic guy that everyone has to deal with.

He was a big elephant that sucked everyone’s energy, in a way.

As an objectively good-looking person, how did you feel about strapping on that all that makeup?

I think at a certain point it becomes easier to try and look ugly and elephantine than it does to look good-looking. There’s something quite releasing about not having to think, Oh, how are my angles? Which pays diminishing returns the older you get anyway.

This is off the subject, but which of your past roles do you think you were the most handsome in?

One called Chronicle of a Death Foretold from 1987. It’s a Gabriel García Márquez novel, and it takes place in Colombia, and it’s about a stranger coming to a village and marrying a girl, and then sending her back to her mother because she’s not a virgin. I was quite good-looking in that.

You mentioned tinkering with the script. What was the hardest thing to get right?

The writing side of it seems such a long time ago — like childhood, or a long summer. A friend of mine who’s a director helped me, and we went to Paris for awhile. We stayed in the hotel where Oscar Wilde died.

What did you get out of that?

Nothing. Some places you get a message, and some places you get no message. Oscar Wilde’s bedroom in L’ Hotel, it’s been redone and it’s got a giant peacock on the walls, and it just felt like nothing to me. On the other hand, I discovered the apartment that he lived in in Naples, and it’s owned by a lady who used to be a concert pianist, and she asked me over one night when there was a full moon, and she played piano and the windows were open onto the sea, and Vesuvius was on the other side. And then there was a message: “Keep going.”

You’re very restrained with the epigrams in the film. The only real famous one you use is “This wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. Either it goes or I do.”

The deathbed room is a character in the movie in a way, so to not mention the wallpaper seemed like a cop-out. And then there’s another one in there: “Why does one run towards ruin?” I think this is essential if you want to understand Wilde. It’s pre-Freudian, but it’s voicing a very Freudian idea.

You also use a quote from the story The Happy Prince: “There’s no mystery so great as suffering.”

That’s quite a modern idea, actually. Wilde is saying that suffering is more beautiful than a great holiday, basically. Suffering is the thing that is redemptive. It’s quite Catholic.

How so?

You limit yourself by what you say. For example, I’m one of those people who if anyone asked me when I was 20 or 30 or even 40, “How are you?” I would always immediately answer, “God, dreadful.” The brain registers that, and then you become that. You lower the possibilities for yourself. Not that I want to be a happy-clappy positive freak either.

Do you agree with it?

I think life is struggle. I think we’ve developed a notion now that life shouldn’t be struggle, and that’s quite dangerous. Obviously it’s very appealing, that none of us should struggle, but at that point, we’re just blobs. Struggle is the thing that defines us. Certainly on this film, the struggle was as important as the doing. I was traditionally a quite flaky person, so to have as much tenacity as I managed to have on this movie, it’s been an eye-opening experience. I have much more capacity than I thought. I think I limited myself.

When someone asks you, “How are you doing?” today, what do you answer?

“Dreadful as usual.”

But it’s a different dreadful.

It’s a different dreadful. Now I’m 60 years old, of course I feel dreadful. I haven’t turned 60 yet, actually. I’m still 59. But it will be … there’s no surprises.

What do you mean?

When you’re a baby, every color is new. I don’t know if you can remember, but I can remember seeing certain colors for the first time. I remember a shocking pink alarm clock and just looking at that pink, though that’s not what defined me as gay. I can remember hallucinating at this sudden new sensation of color that I’d never seen before. Purple too. I love purple. But now show me shocking pink or purple and I’m like [shrugs]. That’s what Oscar Wilde said, funnily enough. When people asked him why he didn’t write anymore, he said, “I wrote when I knew nothing of life. Now that I know it, there’s nothing left to write.” It’s a lie, actually, but it’s a clever one.

What’s one thing you wish you would’ve known about directing yourself?

That I should’ve done it earlier! I just really liked working with me. I liked my ideas, and we were in tune. There wasn’t any lack of clarity about it, and I didn’t feel I had to negotiate a relationship with another person apart from myself. I took such care with myself in the edit, and I helped my performance considerably.

What was your directing style with the other actors?

I gave them two takes, and I gave myself 15.

Really?

No, I didn’t have a directing style with the other actors. I guess I had a camera style more than anything else. We were mostly handheld, so the camera was weaving in and around us during the action.

Why did you want so much handheld?

It gives the film the texture of voyeurism and an intimacy, rather like … have you ever been on a ghost train?

What’s a ghost train?

It’s these trains that go through tunnels and skeletons and things like that come out. You go up to a door and it opens and you go “Ah!” It gives the movie that quality somehow.

It’s a style I really enjoy when I see it in period pieces.

Also, to do the other version, I would’ve needed to have lots more money. The conventional version takes such a lot of time, because you have to have the big shots and tons of tracks. I definitely didn’t want to make a snotty old biopic. I wanted it to look like a cluttered dream of someone dying. The scenes that became too static were the ones that aren’t in the film, actually. When it became static and conventional, it turned into Downton Abbey.

Another thing that makes this movie different from Downton Abbey is there’s a little bit of full-frontal male nudity.

I didn’t realize there was any, hardly. There’s two bits of nudity. But that’s not very much. Is that a shocking thing, do you think?

It’s not so much shocking, just that I’ve noticed it in a few films this fall. It seems like it’s a taboo that is quietly being broken.

That’s great. When I started off in cinema, everyone was nude all the time. Now, we’re in a new Puritanism I suppose, but a little bit of nudity … [shrugs]. What I’m not crazy about in movies, funnily enough, is sex.

Why not?

It’s very difficult to film. I always hate the noise of snogging. I don’t know why. I would definitely go for a more “silver screen” version, when one person kissed up there and the other down there, and they didn’t have any of those … noises, which I don’t think are very attractive.

You’ve been pretty open about the fact that coming out early in your career hurt you.

I’ve never really been that open about that. All I’ve said about that, to be honest, is that it’s not ideal. It’s obvious that it’s not.

If you had been born 20 years later than you were, do you think your career would have been different?

Well, now is a moment of great opportunity for everyone. It feels to me that, for your generation, the future’s up for grabs. When you see what’s happening, you can’t but fail to be thrilled, particularly if you think of it in terms of this film: 117 years is nothing in the total human experience. It’s like a millisecond.

I read that when you moved to London as a teenager, it had only been seven years since Britain decriminalized homosexuality. You realize it’s no time at all.

The strange thing about that was, being gay in the ’70s was in one sense being royalty. It was very hip to be gay, there was an amazing ambiance of equality. But cinema didn’t run along the same lines. It was still fairly old-fashioned, very conservative, and a boys’ club. That was very confusing for me as a young person.

Do you feel that’s still true today?

In the last 15 or 20 years, to give the boys’ club their due, I think they’ve changed. But there is still a boys’ club mentality. For example, it seems to be all right now that a gay actor could play a gay role, but why isn’t the gay actor playing the straight role? The straights can do anything. They can play a gay part — “Oh, he was great in that role” — but the reverse is unimaginable. It’s a phobia that’s not about violence, it’s about an attitude. They can’t imagine that the gay guy could get it together to play love scenes with a woman, and their excuse is the audience would not accept it. But the audience don’t have those kind of views, really. They just want to just be entertained.

You very famously played the “gay best friend” role in My Best Friend’s Wedding and The Next Best Thing. I was wondering how you feel about those types of roles now.

Well, it was a great opportunity, but the difficult thing was I wasn’t going to be able to graduate to another kind of role. I think that’s a role that you can only be exciting in a couple of times, otherwise it becomes, Oh, that again. You can’t just flog an idea to death like that. I think that was the problem for me: I didn’t ever manage to segue into other types of roles.

What does your career need right now?

I need now for the universe to come in and be more helpful. You need to have some producer who wants to kill for you, and you need to have representation that wants to kill for you. These days, you can’t do all these things on your own, you’ll go mad. When you look at some directors, they’ve got people behind them pushing and elbowing everyone out of the way. Everyone needs that kind of protector. Not a patron so much, but some crafty bitch who won’t worry about everyone hating them. I would love a producer who believed in me so much that they would take no nos for an answer and get everything off the ground, and I would just be able to roll in, swishing.

I’ve seen some Oscar buzz for you around this film, and I know that you’ve had mixed feelings about awards ceremonies in the past. I was wondering what your thoughts are about campaigning for this movie.

I don’t really have any. I never thought of it as a possibility. All I’m concerned about is trying to get people to come see the movie. I haven’t been here since 2004, so I don’t know how everything works. But I’m desperate for any accolade and recognition that I can get, and that’s maybe what would get me the patron.

You haven’t been to America since 2004?

I did a play here in 2009 and another play here in 2016. But that’s all.

I was going to ask you, from a distance, how you think the country has changed since ’04.

There’s no more limos. What’s happened to limos? The whole point was limos, and now they’ve all gone. Now everyone’s trailing out of those big vans. That’s not very chic, I don’t think. I loved limos. That’s the main thing. (A) I want limos back. (B) I don’t know, but it’s a mess obviously. But our country’s a mess, too.

What do you think is more of a mess, Trump or Brexit?

Brexit, because it’s forever. Trump, whatever. Even Kavanaugh as a Supreme Court judge is not forever, even if it is for a long time. I think this is a good film for Trump’s America.

How so?

Because it’s about what could happen to us all.

Ostracized, left penniless, have everything taken from us?

De-gilded.

This interview has been edited and condensed.