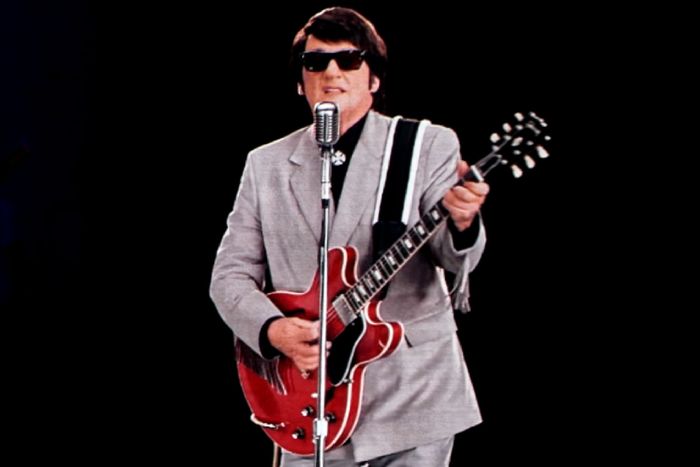

From a puff of smoke at center stage, the legendary crooner appeared, in dark glasses and a gray suit with a black shirt underneath, and his silver crusader cross necklace. He held a red Gibson guitar with a cord plugged into nothing at all, and turned to acknowledge the orchestra before beginning to sing “Crying.” The crowd gasped.

I’d arrived with a vague idea of what hologram live performances might be like, having seen the cell-phone videos of Tupac playing Coachella from 2012. But part of me expected that the awe of that night had come from low visibility on the sprawling lawn and the less-than-sober state of the crowd. This was different. The Wiltern is a 1,850-seat theater, the crowd there was older and just about a beer deep, and the stage was well lit. And yet, Roy Orbison looked … not alive exactly, but real. When the hologram sang the dramatic last bar of “Crying,” we began to cheer. It was unclear whom exactly we were cheering for. Nonetheless, the hologram thanked us and the orchestra started up again.

To be clear, the holographic tech created by BASE Hologram (which is currently touring both a reanimated Roy Orbison and Maria Callas) is breathtaking. The hour-long performance went off without a hitch — the lips synchronized with the vocals, the fingers found the correct frets on the guitar. Orbison’s jacket even had frills along the arms that fluttered believably as he strummed and as he turned to his band. Only as he entered from and exited center stage were we reminded of the trick of it all: This was a concert, but also a magic show.

In the age of the nostalgia tour, when bands get back together to play their classic albums to sold-out arenas, the hologram concert feels less jarring than it may have in previous years. The music industry, struggling to find revenue sources as streaming takes over, has begun to aggressively tap the Remember Those Guys market. Goldenvoice’s Desert Trip, (nicknamed “Oldchella, because of the average age of its performers: 72.5), made $160 million in 2016; the inevitable Holochella, freed from the demands of grisly legends who need things like food and water and money, will be much cheaper to book. And in many ways, Orbison is the perfect muse for BASE Hologram. The Big O was notorious for standing still as he performed, so the hologram needs only to strum and occasionally turn to his band to look authentic. He also has a distinctive look, music built for an orchestral backing, and enough memorable songs to fill a set. Their ultrarealistic Orbison hologram, built from film of a recorded body double and CGI, can play the hits until the end of time. And he’ll never bore a crowd by insisting on playing his new stuff, because there’ll never be new stuff.

But despite the advantages of Roy-as-hologram, building a facsimile Orbison is an especially egregious missed opportunity. The Texan singer was a star in the early 1960s, but then faded as the British Invasion changed rock and roll by the middle of the decade. It was a handful of memorable covers — beginning with Linda Ronstadt’s “Blue Bayou,” which charted in 1977, and then Don McLean’s “Crying” from 1980 — that brought Orbison back to the forefront of people’s minds.

But it wasn’t until “In Dreams” appeared in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet that Orbison’s career was fully revived. As Dennis Hopper’s haunting Frank Booth eagerly mouths along to Dean Stockwell’s lip-synced rendition of the Orbison classic, the film crescendos. Orbison’s morose crooning, used by a master like Lynch, transformed it into a whole new piece of art. “The candy-colored clown” became the stuff of nightmares; the song’s jilted protagonist began to sound deranged. Orbison told Nick Kent in an interview for The Face Magazine, which was published months after his death, that he was at first shocked by Lynch’s reinterpretation of “In Dreams.” “But later, when I was touring, we got the video out and I really got to appreciate not only what David Lynch gave to the song, and what the song in turn gave to the film,” he said, “but how innovative the movie was, how it really achieved this otherworldy quality that added a whole new dimension to ‘In Dreams’.”

Orbison paired perfectly with Lynch: He hearkened back to an idealized time, but one awash in unreality. He dyed his light hair jet-black and he sang old-fashioned ballads as Beatlemania began. And because he reclaimed prominence through other artists’ reimagination of his work, our memory of him is both layered and clouded. But the holographic Orbison is neither Ronstadt sings Roy, nor Lynch adding visuals to an Orbison original. This is Orbison’s voice synced to an Orbison approximation to let an audience watch him as he may once have been. It’s a fantastically accurate Elvis impersonator, not Tom Petty covering “Wooden Heart.” It’s magic, but not magical.

Even as a skeptic, I was awed by the accuracy of the hologram. But what if the Orbison hologram was used in a Lynchian sense to add a “whole new dimension” to the art? What if Orbison’s image skipped during a song or the backing track slipped offbeat ever so slightly? What if the performance managed to be haunting, to play with the idea of summoning a great one from the dead?

The inherent flaw of the live hologram is the unbreachable space between audience and performer. Though good enough to trick the eye, part of the performance still feels like an orchestra playing along to Casablanca. Throughout BASE Hologram’s promotional material, they ask for the suspension of disbelief. And during each song, it was not hard to envision, briefly, that Roy Orbison was back to sing his chart-topping classics again — he was right there, onstage, after all. But when the song stopped and the crowd cheered — for the BASE engineers, or for the orchestra, or for whatever Orbison once meant to them — it became clear what wasn’t possible to conjure in projected light. Live performance is about missed chords, cracked voices, and the energy of seeing something new and specific to a moment. It’s about a singer or a band playing for the people in front of them that certain night. Hologram Roy sang each song perfectly, at times even passionately. He returned for an encore, as if summoned by the cheers. He was perfect — he moved like Roy and sounded like Roy. Undoubtedly, he’ll never miss a note the whole tour.

As I left the theater, a man turned to me to say, “You think that was cool — wait till they make a Freddy Mercury hologram!” It did feel like this was the beginning of something. Or perhaps it was the end.