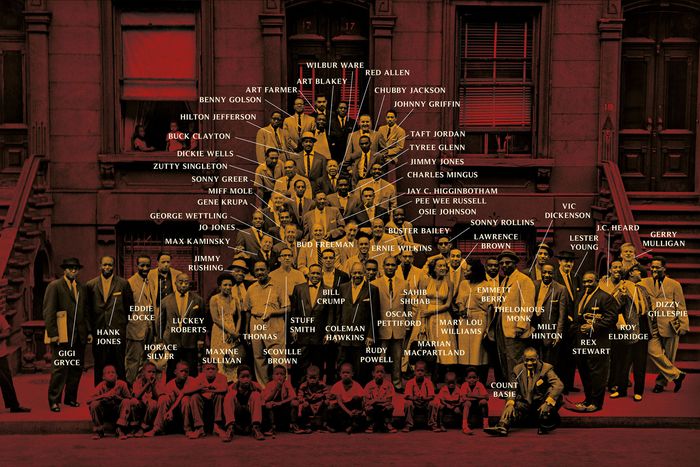

Sixty years ago, 57 jazz musicians gathered in front of a Harlem brownstone at 17 East 126th Street, between Fifth and Madison Avenues, for a photo shoot. Though it didn’t seem like a big deal at the time, the resulting photograph, taken by Art Kane and published in the January 1959 issue of Esquire, went on to become one of the most iconic images in jazz. The shot, which featured such legends as Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Coleman Hawkins, Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Lester Young, and Mary Lou Williams, captured the music at an inflection point. The next year, young innovators like John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Dave Brubeck would record now-canonical albums that changed jazz forever.

Jazz is often cast in terms of forward progress, each epoch neutering the previous one — small-group bebop usurping big-band swing, for instance. But “A Great Day in Harlem,” the subject of a recently published book called Art Kane: Harlem 1958, which includes several outtakes from the day, is a portrait of harmony, old and new guard alike peaceably intermingling. The photo suggests that jazz is as much about continuity and tradition as it is about radical change.

Of the dozens of musicians who showed up, only two are still alive: the tenor saxophonists Sonny Rollins and Benny Golson. At the time, Rollins, who had already recorded such albums as Tenor Madness, Saxophone Colossus, and Way Out West (recently reissued), was a titan of his instrument. But Golson, who has composed some of the most enduring tunes in jazz, including “Whisper Not,” “Stablemates,” “Killer Joe,” “Blues March,” and “I Remember Clifford,” had yet to prove himself, by his account. “I was the new boy in town,” he recalled.

In a recent phone conversation, Golson, who turns 90 in January and wrote a foreword for the book, reflected on his career in jazz, looking back on that morning in August 1958 when he appeared at the 10 a.m. shoot — unreasonably early by the standards of jazz musicians, who tend to keep unreasonably late hours — to find so many of his idols in attendance. “It was,” he said, “a small miracle.”

Tell me about the photo. How did you know to show up at the spot at 10 in the morning?

Do you remember someone named Nat Hentoff?

Of course.

During that time, he was writing for DownBeat before he became involved with politics, and he was the one who called me. At that time, I was the new boy in town, and I just thought it was another photograph — go up there, click, and that was it. But when I got up there, I saw all of my heroes, and then I wondered, Why in the heck am I here? Nobody really knows who I am. When I got there, most everybody who was supposed to be there was there, but the problem was, as Art [Kane] was trying to get everybody together collectively, there was a bar on the corner, and he had a hard time getting everyone back from the bar at the same time. Art was such a patient guy, he was trying to get that all together. It took over an hour to get that picture. And when we finally took the final shot, Willie “the Lion” Smith was in the bar — he didn’t make the shot.

Wasn’t it a little early to be drinking?

Well, it seems like this was a special occasion and they wanted to augment it a little bit.

Where did you live at the time?

Where I lived at the moment was 55 West 92nd Street. I was on the fourth floor and Quincy [Jones] was on the sixth floor. We were in the same building, but somehow he wasn’t called or he didn’t make it. Something happened, and he wasn’t in the photograph. In fact, there were a lot of people who weren’t in the photograph. But you know, a lot of people were working: John Coltrane, Miles, Duke Ellington, Woody Herman. Buddy Rich should have been there. Greatest drummer I ever heard in my life. I’m not talking about his style. His technique — nobody could touch that man. I’m telling you, no drummer that you ever speak of — Max Roach, Kenny Clarke, Gene Krupa. No way. He was in a space by himself, and I don’t know if people realize that.

That’s interesting that you should say that because he seems to be sort of excluded from the pantheon.

That’s their mistake. But his personality was horrible.

You mentioned that you didn’t feel like you belonged in the company of some of the other sort of legendary musicians.

Right, I hadn’t really proven myself by then. Most of the guys there, I knew who they were, but I didn’t know them. Who did I know? I knew Dizzy Gillespie because I was with his band. I knew Gigi Gryce — a couple of months after that picture was taken, he was the best man at my wedding. I knew Art Farmer, who is standing beside me, and I knew Art Blakey, and I knew Sonny Rollins. The other people I didn’t really know. Of course, as time went by, I got to know most of them, but initially, I was the new boy in town. I tell my audiences, a situation like that, I could have appeared there nude and nobody would have paid any attention to me.

I feel like you’re selling yourself short. By the time this photo was taken, you had already written “Whisper Not,” and you’d also put out a few records under your own name.

Well, what really got me started was when Miles Davis record “Stablemates” [in 1955]. Before that, I’m embarrassed when I look back. I would meet people and give them a lead sheet. Nothing ever happened. But when John Coltrane left to join Miles, I saw him one week later on Columbia Avenue, the street in North Philadelphia where John and I lived — I lived on 17th Street; he lived on 12th Street. I asked him how it was going with Miles because I knew he had to come abreast with the repertoire, and he said it was going good. Then he added, “But Miles needs some tunes, do you have any?” Are you kidding? I had written this oddball tune called “Stablemates.” John took it with him, and I didn’t think any more of it because nobody was recording anything of mine. James Moody recorded the very first thing, and it didn’t get much attention. Then I ran into John about a month later, and he said “Guess what?” I said, “What, he do that tune I gave you?” He said, “Yeah, we recorded it!” I said, “What? Miles recorded my tune?” He said, “Yeah, Miles dug it.” And when I saw Miles, Miles said to me, “What were you smokin’ when you wrote that?”

Miles is also sorely missing from that photo, of course.

And Red Garland, who was from Philadelphia. He wasn’t in the picture, but I assume if he were in town he would have been. But then, like I said, lots of others weren’t there. And we never knew. What do you do when you get a magazine and you finish reading it? The one that had the photograph in it, with the picture, I threw it in the trash, like we always do. And then it started to gain fame. Those who were still alive, we couldn’t believe it. When I signed with Columbia Records, Bruce Lundvall, he had the picture, and I lamented to him, “Ah, I had that picture, and I threw that magazine away!” I went back to Philadelphia — I was just about to sign with the label — and a couple of weeks later, the doorbell rang and it was somebody with a big package; he’d sent me a big-size copy of that picture, which is still in my house in Los Angeles. That picture really became iconic, and then ones, twos, threes, everybody started to depart, and then we finally wound up with Sonny Rollins and me.

Do you walk by the spot at all?

Never, never, never; it’s out of my territory. It’s up on 126th Street on the East Side. I never go on the East Side for anything. Not that I try to avoid it. What I do never takes me there. So that’s the way it is.

It seems like you’re in pretty good shape.

You know, this January, I’ll be 90 years old. Now, I tell my audiences, it’s a good thing I chose music because I’m still playing. It’s a good thing I wasn’t a quarterback. Who’s ever heard of an 89-year-old quarterback? So I’m still functional. I still do what is in my heart to do. I’m still able to play, nothing wrong with my mind and my fingers. [When] I play my solo now, there’s a chair right by the piano. I sit down, but I’m still playing. Of course, Sonny will never play again. Tragic.

What are you working on lately, anything new?

Nothing new. What has happened to me now, after being married 60 years — my wife has Alzheimer’s, and my life is not the same, not the same. She doesn’t know who my daughter is. Sometimes she knows who I am. Sometimes she’ll ask me where do I live. It’s funny and tragic at the same time.

That’s a good way to look at it.

So I don’t want to be away. We had a place in Germany for years — I had to give it up, sell the car, give the piano away, because I can’t be in Germany during the summer, because she’s here in a nursing home. So we gave it up. And I want to be here as much as I can. I don’t want to be gone too long. I don’t want to do anything that’s going to take me away too long. Yet I have to work; I’m not rich! So my life is quite different. Sometimes I feel like just lying down and crying.

So you’re mostly performing now?

No, I also do master classes. I’ve been up to Hartford and Stanford and throughout Europe and different colleges. They want me because I’m old and I have lots of information. I’ve seen it all, Matt.

I feel like you and Wayne Shorter —

That guy doesn’t show his age, does he?

That’s true, but it’s interesting that you’re both tenor saxophonists and you’ve both written such enduring tunes. I feel like it’s not often the case that tenor sax players are composers.

He’s of the same ilk, absolutely. He’s still playing, and he sounds great.

A lot of the tunes that you wrote were very memorable, melodically speaking, but I don’t hear that as much in jazz nowadays. Do you think there’s less of an emphasis on melody in modern jazz?

Not as much melody as there used to be. Some of the tunes sometimes sound athletic, you know? The memorable thing — you know, I love writing ballads, but there’s no real room for ballads anymore (like Peggy Lee, Diana Ross, Sarah Vaughan, Mel Tormé, Ella Fitzgerald), that’s kind of gone by the wayside a bit.

In 2004, you were featured in the Steven Spielberg film The Terminal, with Tom Hanks. Do you keep in touch with him?

I hear from Tom all the time, not so much from Steve. His wife, Rita, she’s a singer. They’re both sweethearts. But they’re ordinary just like you and me. So is Steven.

Did that movie bring new listeners to your work?

They had a little gathering out there in Hollywood once, Dick Van Dyke was there. Incredible. This music has been fantastic for me. I love it. And you know, years ago, I used to be a truck driver before I really got started professionally. The first job I had, I used to deliver furniture. And then I got another job where I became an expert at hanging these big mirrors. I could put up a mirror in 20 minutes. I hated both of the jobs. And when I went in and told ’em I wouldn’t be coming back, they all asked me what I was gonna be doing. I said, “I’m gonna be a jazz musician.” And they all started to laugh. But I never went back. And there’s nothing wrong with those kinds of jobs, there’s nothing wrong with hard work, but I tell you, and I tell my audiences, being a musician is so much better than being a truck driver.

I don’t think anyone would disagree with that.

Nothing wrong with it at all, and I appreciated the money, but I hated every moment of it. I watched the clock from 8 o’clock till 5 o’clock, every day.

I don’t blame you.

And here I am at the end of my career. We’ve got so many young ones, and I’m inspired when I see what they’re doing. They’re doing it much faster. When I was coming up, you couldn’t go to college and get a diploma for jazz. When I went to college, I was told that if I was caught having anything to do with jazz, I would be expelled from the college. I was playing in Washington, D.C., and I used to sneak over the wall at night in the back, after having played the gig, and I went to work one night, went up on the bandstand, and I turned around and at the first table there was the head of the theory department. And when I finished playing, what I was expecting was, “See me in my office tomorrow at 9 o’clock,” but he said to me instead, “Great set,” and nothing else was ever said.

I’m wondering a little more about the photo because you’re standing behind Art Blakey. The shot was taken in August 1958, and then two months later, you recorded “Moanin’” with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. It’s one of the canonical albums released in 1959, along with Kind of Blue, Time Out, The Shape of Jazz to Come, Mingus Ah Um, Giant Steps …

That almost didn’t happen, and “Moanin’” almost didn’t happen. During breaks, sometimes Bobby [Timmons] would have a little thing he’d play, just a little lick, nobody really played any attention to it. But as time went by, we were getting ready to record. I thought about that, and I said, he’s got eight bars there, but he doesn’t have a bridge. I called a rehearsal, and I said, “Bobby, you know that little thing you play? You’ve got a potential tune there. We’re gonna sit here and make up an eight-bar bridge.” He said, “Oh, this is nothing.” I said, “Bobby, it’s got great potential, try to put a bridge to it.” And so he did. In about a half-hour, he had something together, and he played it for me. I said, “Bobby, no, you don’t have the same feeling as the original lick.” He said, “You write it.” I said, “No, Bobby, this has gotta be your tune. Try again.” And so in 15 minutes, he had a bridge, and he played it for me, and I said, “That’s it.” I said, “What are you gonna call it? What does it make you think about?” He said, “Maybe ‘Moanin’’?” I said, “Okay, call it ‘Moanin’.’” I said, “We’re going to play it tonight, and the audience is going to tell us what they think of it.”

I had just come in to the band, and Art wasn’t making that much money. There were so many things wrong, and I talked to him sometimes. One of our conversations during the break was, “Art, the way you play those drums, you should be a millionaire.” And when I mentioned the word millionaire, his eyes widened. And he said to me, “What do I do?” And I had the nerve to tell him, “Do everything I tell you to do.” And he said, “What do I do?” I said, “Get a new band.” He said, “All right, tell them they’re fired.” I said, “I can’t tell them they’re fired.” I had just come into the band, but eventually it did happen, and it’s terrible because I knew all the guys, but the guys were going to sleep on the bandstand and nodding and all kinds of crazy stuff.

And during all that time, everybody was listening to what I was saying. I said to Alfred Lion at Blue Note, “I have a photograph here, Alfred, that one of the fans took of Art. It’s a head shot. I’d like that head shot on the cover.” And they did everything I was telling ‘em to do. Up to this day, I can’t believe it. Incredible!

Sounds like it was more your band than Art Blakey’s at the time.

At the time, yeah, because I would get the money, and I would pay the men.

In Jean Bach’s documentary about the photo, A Great Day in Harlem, Marian McPartland says something early on that sort of struck me as insightful. She wonders aloud what it would have sounded like if every musician had brought his or her instrument to the shoot and everyone had played. What do you think that would have sounded like?

That never crossed my mind. That would have been something. How about that. We’d have had somebody from every instrument — piano, bass, trumpet, trombone. My goodness! Hmm. That never crossed my mind.