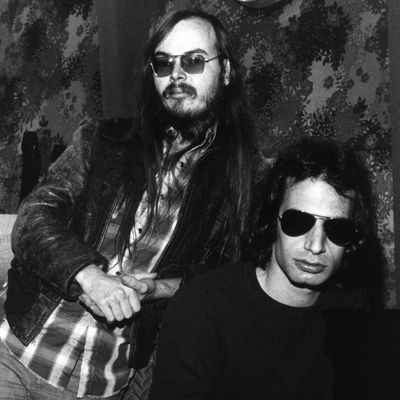

Listening to pretty much any Steely Dan song can best be described as swaddling into a virtuosic sonic cocoon, welcoming a dozen-plus instrumentalists to take you on an unforgettable journey of rock bliss. “Time Out of Mind” for when you want to boogie down. “Deacon Blues” for when you’re feeling sentimental. “Josie” for further boogying. Unsurprisingly, to get perfection you must demand perfection, and frontmen Donald Fagen and Walter Becker’s commitment to audiophile paradise wasn’t lost on the carousel of studio musicians who were recruited to work with them throughout their ’70s and ’80s heyday. These album bootcamps were hellish enough to break even the most gifted of artists — if you weren’t up to snuff, you were cut, but if you remained, well, you had a personnel credit on Aja. And who wouldn’t want a personnel credit on Aja?

In recognition of Fagen taking Steely Dan back to the Beacon Theater for another themed residency — Becker died last summer of cancer — Vulture compiled a few notable stories of what exactly it was like for musicians to work alongside The Dan and the crushing blows to their egos that ensued. Let’s just say they weren’t averse to gatherin’ up the tears.

Mark Knopfler

When Fagen and Becker were in the midst of recording Gaucho, they listened to Dire Straits’ debut album and were particularly impressed by frontman Mark Knopfler’s guitar work on the seminal tune “Sultans of Swing.” As such, they invited Knopfler to take a crack at the solo on “Time Out of Mind,” despite Knopfler not being a sight reader — the preferred Steely Dan way of recording. Knopfler soon grew frustrated by the long, repetitious recordings in the studio, doubled with Fagen and Becker’s brash manner of criticizing his lack of progression. In total, Knopfler recorded over ten hours of guitar work, only for about 15 seconds to be used in the song’s intro. “It was a strange experience,” Knopfler later recalled, “like getting into a swimming pool with lead weights tied to your boot.” Becker later added of Knopfler’s frustration: “I think he definitely felt that, because he would play something and it was okay, then we’d like it later.”

Jeff Porcaro

As one of the numerous drummers recruited to attempt the drums for Gaucho’s title track, Jeff Porcaro — perhaps best known for being Toto’s drummer, although he also worked on Steely Dan’s Katy Lied and Pretzel Logic and is generally regarded as one of the best studio drummers in modern history — admitted Fagen and Becker’s demands were close to driving him to the point of insanity. “From noon till six we’d play the tune over and over and over again, nailing each part. We’d go to dinner and come back and start recording,” he explained. “They made everybody play like their life depended on it. But they weren’t gonna keep anything anyone else played that night, no matter how tight it was. All they were going for was the drum track.” Never totally satisfied by Porcaro’s drumming in a single take, it’s rumored the drums on “Gaucho” — a song clocking in a 5:32 — was assembled and sliced together from 46 separate takes.

The “Peg” musicians

The recording of Aja’s “Peg” — particularly the 30-second guitar solo — is one of the most notorious in the band’s history, in that six guitar soloists were brutally fired before Fagen and Becker eventually warmed up to session musician Jay Graydon and gave him the gig. Compared to other musicians who were brought in to work with them, though, Graydon had a surprisingly pleasant, albeit occasionally stressful, time. “For about an hour and a half, I’m playing my hip, melodic kind of jazz style. Then Donald says to me, “Naw, man. Try to play the blues,’” he remembered. “The whole thing probably took about four, five hours. Including taking some breaks. They knew they were onto something.” Other musicians, such as “Peg” rhythm guitarist Steve Khan, weren’t as kind with their words. “Having the money, and the power of guaranteed sales, is a license for abuse,” he recalled. “What they might waste on one or two days of recording to get a single track, most artists, like me, could make an entire record for that.” Added Elliot Scheiner, who was the lead engineer on the track: “A band would come in and record and two hours later [Becker and Fagen] would look at their producer, and say, ‘Fire this band. Let’s go with somebody else tomorrow night.’ It’d be different bands every night to get the same song.”

Lenise Bent

We’d be remiss if we didn’t include this anecdote about seasoned studio engineer Lenise Bent, who worked with the band during their Aja sessions. It was the recording of the song “Home at Last” that brought her to a breaking point, due to Fagen and Becker’s insistence on getting two words, two syllables, absolutely perfect. As remembered by Dick LaPalm, Bent’s friend and publicist extraordinaire:

‘Dick, I have to talk to you.’ She put her head down on the desk in her arms and said, ‘Well-the, well-the, well-the.’ I said, ‘What are you doing?’ Lenise looked up and said, ‘Dick, I have to get off the Aja session. They worked on the words ‘well the’ for six hours last night. All they did was work those two words for just the right sound for hours. I really have to get off the session.’

The Gaucho drummers

Uniformly unsatisfied by the rotation of drummers who were brought in to try songs such as “Hey Nineteen,” “Glamour Profession,” and, yes, “Gaucho,” Fagen and Becker convinced the band’s record company to drop tens of thousands of dollars to design a machine that could fulfill and execute such precise drum tracks in favor of humans — a machine that was lovingly referred to as Wendel, created by recording engineer Roger Nichols. “We found there were certain feels that we couldn’t get out of real drummers,” Fagen explained at the time. “They weren’t steady enough. So we had to design something that would do it perfectly, but with some human feeling, the right amount of layback. Wendel can play exactly what the drummer plays.” To add insult to injury to those rejected drummers, Wendel was awarded with a platinum record.

Victor Feldman

A jazz musician who specialized in piano, vibraphone, and percussion, Victor Feldman showed up a few times throughout Steely Dan’s discography, forming a mutual respect with Fagen and Becker in the process. However, a recording session for The Royal Scam’s “Green Earrings” tested their relationship when his keyboard playing wasn’t vibing with the band’s vision — as Fagen admitted years later, they punished Feldman by only letting him play a salt shaker for a daylong studio session.