Let’s dispense with any niceties or equivocation: 2018 has been a year of Asian-American excellence. Crazy Rich Asians smashed (admittedly low) box-office expectations and led the way in a very good year for Asian-American pop culture, where more Asian-Americans appeared on screens, worked behind them, made music, cracked jokes, and published books than ever before. I used to be able to keep track of every single one because there were so few. Now, I’m merely aware. For instance, I know there is a hot Asian-American actor playing the first gay male surgeon on Grey’s Anatomy, something so squarely in my wheelhouse that my lymph nodes are shaking, but I have yet to watch it. Why? Because there is, finally, some choice in the matter, and I’m not so desperate for a drop to quench my thirst. (Although I’m going to catch up, because I’m still thirsty.)

Here’s an incomplete list of some things that gave me joy this year: Sandra Oh was ferociously good in Killing Eve; the trio of Kaliko Kauahi, Nico Santos, and Nichole Bloom consistently delighted on Superstore; we got to see Manny Jacinto, Mitch Narito, and Eugene Cordero bro it out in The Good Place episode “The Ballad of Donkey Doug”; Hong Chau continued to make every little role she does feel big (Homecoming and Forever); Japanese Breakfast wrote a gorgeous essay about her mother and H Mart; Chloé Zhao managed to make a movie that felt both expansive and intimate with The Rider; Aneesh Chaganty directed hot dad John Cho in the indie thriller Searching; Bowen Yang delivered some expert lip syncs; a mother ate her (metaphorical) son in the Pixar short Bao; Lana Condor charmed in To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before; Ling Ma published the genre-mixing zombie novel Severance; Ali Wong dropped a second comedy bombshell on Netflix, Hard Knock Wife; David Chang pursued his neuroses in Ugly Delicious (particularly the Viet-Cajun episode); the mandarin duck came to town.

Amid this spate of writing, films, and music, there’s still a larger question that lurks behind every conversation around Asian-American representation: What is Asian-American art? Is it simply Asian-American creators making work? Or is there something intrinsically Asian-American about the work that bends genre or medium to itself? While the former is certainly true — Asian-Americans can make whatever they want — for a long time we simply accepted anything as good as long as it wasn’t overtly racist (Ahem, 2 Broke Girls). Asian-Americanness existed as a one-to-one equation of representation. Meaning, most Asian-American actors were cast in “color-blind” parts, where the character and race weren’t linked in any meaningful way: Aziz Ansari as Tom Haverford on Parks and Recreation, Grace Park as Boomer on Battlestar Galactica, Darren Criss as Blaine on Glee (who was assumed to be white). When John Cho played Henry Higgs on Selfie back in 2014, he called the character “revolutionary” because for the first time, an Asian-American man was the romantic lead on a TV show. (Just remember John Cho walked so Henry Golding could fly.)

This flattening is in part because America operates on a black-white paradigm, leaving Asian-Americans caught in another in-between space where they can either be charged for being “white adjacent” or appropriating black culture. There’s a fog of invisibility, of never quite feeling full ownership over “American” culture. The creation of Asian-American identity is itself a response to that myopia — the yoking of vast continents of people, languages, and cultures is only possible in a country that’s unable to contain nuance. But even as Asian-American identity was created as a political tool in response to white supremacy, there’s a generative aspect to it, too. The forced grouping produces empathic ways of looking outward, broadening horizons, and connecting the lines of history and geography.

What has been revitalizing about this year has been the amount of Asian-American work that moved away from the artificial separation of identity and art, and at times, even hit upon similar ideas. It’s slow going because we’re still operating in a system governed by white gatekeepers, but there were more moments where I felt that thing — that Asian-American thing — shudder deep inside my bones. Take the scene in Crazy Rich Asians when Eleanor (Michelle Yeoh) accosts her potential daughter-in-law, Rachel (Constance Wu), on the staircase and tells her, “You will never be enough.” Eleanor’s withering judgment is not just because Rachel comes from no-name Chinese stock (although that too), but that she is too American, and she couldn’t possibly understand the sacrifice required to marry into this dynastic Chinese-Singaporean family. The scene has extra-textual resonance — Eleanor could have been talking about how Asians might view Asian-Americans as incomplete, cultural half-wits.

But perhaps that liminal, in-between space that Asian America exists in — not from here, not from there — can create a genre of its own, rich with themes of alienation, belonging, and longing. Just a few years ago, Master of None aired the “Parents” episode — a gentle, heartwarming look at the misfires between Asian immigrant parents and their second-generation children. At the time, it felt like nothing depicted in popular culture before. What’s been significant in the years since is that there’s more work that captures that rootlessness, and explores its darker parts: The most moving passages in Ling Ma’s Severance were about the protagonist Candace’s memories spending time with her mother as a child in Fuzhou — a place that could only exist in her mind in a postapocalyptic world. (But that feeling that she could never go back home is, incidentally, what inoculates her from the zombie virus.) The fear of incompleteness has been an undercurrent throughout Mitski’s work, but was made explicit in her music video for 2016’s “Your Best American Girl.” Loneliness still reverberates throughout her latest album, Be the Cowboy. In “Nobody” she sings, “I know no one will save me // I’m just asking for a kiss” — a continuation of “Your Best American Girl” where she concluded, “Your mother wouldn’t approve of how my mother raised me // But I do, I think I do.”

There’s another moment in Bing Liu’s documentary Minding the Gap that hits that raw nerve. It follows Liu and two of his childhood friends in Rockford, Illinois, bounded by the experience of domestic violence. In one particularly difficult scene, Liu asks his mother, who remarried a white American man that beat him as a child, whether she knew. She can’t give him a good answer, and you can sense a chasm opening up between them as she struggles to respond in halting, accented English. There is no neat resolution, and much of it is left unanswered. That, too, feels accurate in the way that the generational gap between immigrants and their children can feel like an unclosed wound.

If feeling adrift is melancholic, maybe that middle space can be claimed as a home of its own. The goddess of mellow electronic pop, Yaeji released a single, “One More,” this year that continued the inherent bilingualism in her music where she mixes Korean and English. When she DJs, she layers improvised vocals to her set, adding to the hybrid effect. She makes the hyphenate of Korean-American a style in and of itself.

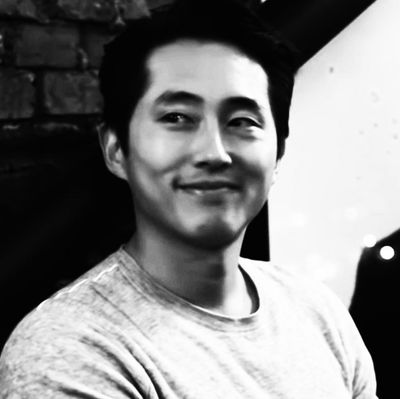

So, too, does Steven Yeun. In his past two roles with Korean directors, he’s been able to explore varying sides of the Korean-American experience. In Bong Joon-ho’s 2017 film Okja, Yeun played a fumbling Korean-American animal-rights activist who speaks mangled Korean. He’s the tragic fool trying to bridge two worlds and failing. In Lee Chang-dong’s 2018 film Burning, he offers a variation: the cosmopolite who moves effortlessly through society, unbound and unbidden, speaking Korean with a chilling textbook accuracy. His origins are unknown — his name is simply Ben — but there’s a recognizable American swagger to his character and the way he looks and moves. Even though the role is completely in Korean, there’s a Korean-American sensibility guiding the part. Yeun’s performances in Okja and Burning are roles only a Korean-American with his level of language facility and artistic ambition could do. What’s more Asian-American than that?

However Asian-American art continues to evolve, it can only get more interesting if there are more conversations where Asian-Americans are unafraid to speak to each other. Something vital happens when we begin to see one another as the people to please, berate, critique, create, and play with. It produces delicious moments of frisson, like Ali Wong telling David Chang that she only wants to know how Asian people rate Asian restaurants, or Hasan Minhaj teasing Queer Eye’s Tan France that, actually, India is the future.

So maybe it makes perfect sense that Crazy Rich Asians didn’t do well at the Chinese box office, because perhaps it wasn’t for them anyway. That dynamic is written into the film, too. The climactic scene of the movie staged a mahjong battle between Eleanor and Rachel, where Rachel decides to give it all up — a winning tile and her boyfriend’s proposal for marriage — so that Eleanor could have what she wants. Instead, she would pick herself — her poor, raised-by-a-single-mom, immigrant, low-class nobody self — because she knew she was enough.