The artist and designer Leonor Fini never considered herself a Surrealist. They were too sexist. And despite a decades-long career in the avant-garde — she was born in 1907, and died in 1996 — she ended up being far less well-known compared to her friends and collaborators, including Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Albert Camus, and Yves Saint Laurent. But the Museum of Sex’s exhibition “Leonor Fini: Theatre of Desire” should help call attention again to her provocative and expansive accomplishments.

It’s the first-ever survey of her body of work, and it winds through a ruby-hued gallery reminiscent of a goth cabaret, complementing Fini’s richly pigmented paintings, film, furniture, costume, and set designs. Included in the exhibit are extravagantly staged photographs of Fini, by the likes of Henri Cartier-Bresson and André Ostier. Fini used fantasy and mythology as a vehicle through which she could subvert male-dominated narratives in Western art that relegated women to the status of subservient muse. Today her legacy is revisited by media and auction houses alike, with San Francisco’s Weinstein Gallery and Paris’s Galerie Minsky asserting Fini’s status as one of the most important artists of the 20th century.

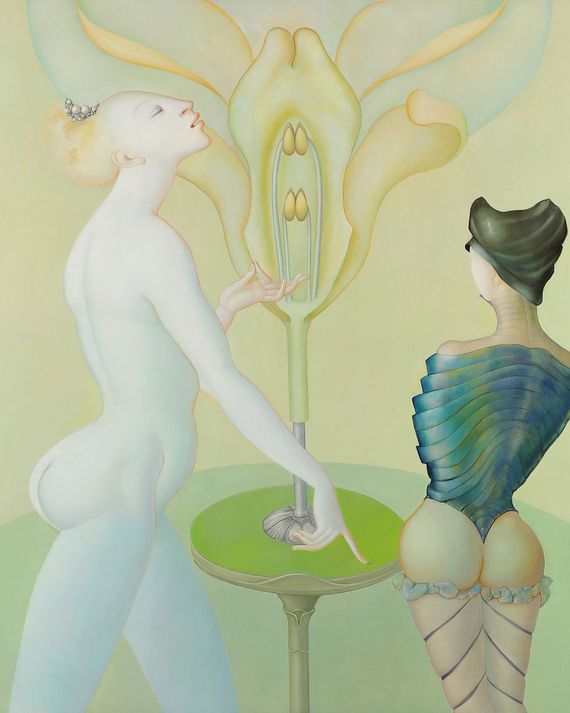

Fini is one of several female Surrealists just now receiving their due. This fall, a retrospective of fellow Surrealist Maruja Mallo opened at New York gallery Ortuzar Projects, marking the first time that the Spanish artist’s work has been shown in the United States in over 70 years. Fini’s artwork exhibited the enigmatic, dreamlike attributes ascribed to works of the Surrealist movement, and earned her international acclaim when she participated in the 1936 “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” exhibit at the MoMA in New York City. But she never considered herself to be an official member of the group. She objected to the misogyny of leader André Breton, who actually excluded female artists from official photos of the Surrealists and believed fervently in the traditional role of woman as erotic muse. Inverting the gendered tropes, Fini consistently depicted men in her artwork as delicate, beautiful beings in need of guidance and protection.

Lissa Rivera, who curated the Theatre of Desire retrospective, attributes Fini’s relative obscurity to the reality that men were predominantly the decision-makers in the art world in the 20th century. “Attitudes at the time she passed away, in 1996, were quite negative and condescending. Her work is very emasculating in a lot of ways, so it probably wasn’t the most comfortable work to sit with, for those who were in charge.”

The sphinx is a recurring motif in Fini’s work. She often styled the mythical creature in her own image and depicted this mythological avatar as a sort of protector or guide of the androgynous males in her paintings. The role of the woman and the sphinx in her artwork was informed by Fini’s study of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams and Sophocles’ Oedipus in her youth. While Dalí and Ernst fixated on the remorse and threat of the sphinx for its role in the tragedy, Fini’s interpretation favors the sphinx’s eventual victory. “She interprets the sphinx as the character with the greatest insight,” says Alyce Mahon, art-history professor at the University of Cambridge and curatorial adviser for “Theatre of Desire.” “Oedipus is blind. He might be cunning, he might be virile, and he might solve the riddle, but he is ultimately revealed to be the fool. Fini interprets the sphinx as the heroine of the story.”

Fini grew up in Trieste, Italy, with her mother, but was often dressed as a boy to evade kidnappers sent from Argentina by her father. It is thought that the time Fini spent dressed as a boy ignited her lifelong fascination with both androgyny and donning elaborate costumes. She is quoted describing her interest of blending the attributes of both sexes in Peter Webb’s biography, Sphinx: The Life and Art of Leonor Fini: “I am fascinated by the androgyne, for it seems to me to be the ideal … I would like to think of myself as androgynous.” She held a lifelong aversion to being labeled in any other way, and would later object to being called a woman artist or a feminist.

Largely self-taught, Fini was deeply fascinated by art and studied works spanning from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Renaissance and the Mannerists. As a teenager, she taught herself anatomy, sketching studies of cadavers at the morgue and read the untranslated works of Freud and Jung. It should come as no surprise, then, that Fini was readily accepted into the Salon Carré of Paris when she moved to France in 1931, at the age of 24.

While Fini got her start as an artist during a brief stint in Milan as part of a 1929 group exhibition, she truly flourished in Paris. Christian Dior, a gallerist at the time, exhibited her works before leaving art for fashion. She counted Surrealist painters Leonora Carrington, Méret Oppenheim, Salvador Dalí, and Max Ernst as close friends. By day, Fini worked for hours on end in her atelier but enjoyed a lavish nightlife, attending parties and balls in elaborate costumes with a man on each arm. Her lovers, who included Ernst, painter Stanislao Lepri and writer Constantin Jelenski, lived with her in ménages à trois and served as her muses during the daytime. “It’s this sense that her art has been an extension of her real or fantasy lives, a stage for her seductive ways, that often dominates readings of her work,” explains Mahon. “In the exhibition, we’ve very much explored the theme of theatricality; it has been not just to show her as a female troubadour, as Giorgio de Chirico described her once, but very much to show her as an excellent artist.”

Fini’s art, for all of its subversive thematic exploration, aided her rise to fame during her lifetime. Now, it has finally begun to receive its much-deserved credit from the art world at large. Echoes of Fini’s legacy reverberate across today’s fashion and design landscape. The Elsa Schiaparelli’s “Shocking” fragrance bottle she modeled after Mae West’s figure, on display as part of the “Theatre of Desire” exhibition, directly influenced the famous Jean-Paul Gaultier perfume bottle, which Kim Kardashian-West has now imitated (lawsuit from Gaultier pending). Also on display are Fini’s 1942 costume designs for George Balanchine’s Palais de Cristal; the designs later inspired Balanchine’s 1967 ballet, Jewels, which recently wrapped its latest run at the New York City Ballet. Finally, Maria Grazia Chiuri dedicated Dior’s spring 2018 couture collection to the late Fini with a possible nod to her affinity for showing up to parties in Paris wearing nothing but a cape of white feathers and boots. “Periods of interest in Fini emerge, but having her work fit into the narrative in a more permanent way is something that I feel this show has a chance of achieving,” says Rivera.