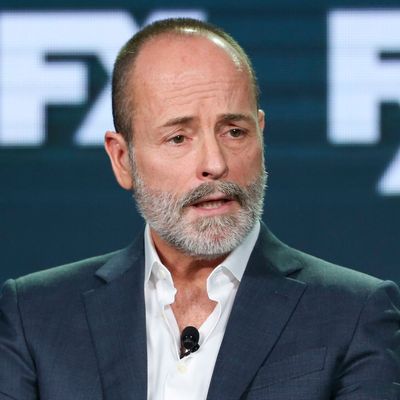

FX Networks chief John Landgraf is once again lashing out at Netflix, this time taking issue with the streaming giant’s decision to self-report viewership numbers for a handful of titles, including Sex Education and You. Appearing in front of journalists at the TV Critics Association winter press tour in Pasadena on Monday, Landgraf accused Netflix of both misrepresenting the actual audience for its shows and creating a false impression of how its programming slate is performing with its subscribers. “When applying industry standard, accepted metrics to all their programming, the list of shows on their platform that would be considered commercial failures is long, and their true batting average would be viewed as unimpressive,” the exec argued. It was a stunningly direct attack, even for a longtime Netflix skeptic such as Landgraf.

Landgraf’s latest charge was sparked by Netflix’s decision last month to pepper its fourth-quarter earnings letter to shareholders with some carefully selected data points about recent programs. Breaking from its usual custom of not disclosing specific numbers about how its shows perform, the streamer told shareholders (and thus the world at large) that its recently acquired Lifetime drama You and its new dramedy Sex Education were on track to be seen in 40 million member homes within their first month on the service. “The numbers look really big and provoke the notion that many shows on their platform are gigantic hits that are watched more than the shows on broadcast or basic cable,” Landgraf said. “However, if you dig a little deeper, Netflix is not telling you the whole story because the numbers they issue do not follow the universally understood television metric … which is average audience. Anyone who’s read Netflix’s statement about You would likely assume they were giving an average audience number because that is how scripted television has always been measured. They would simply think, Forty million households are watching You? Wow, I better check that out. It must be the biggest hit on TV.”

It is not wrong of Landgraf to take issue with the idea that 40 million people — or even 40 million homes — have watched all of season one of You on Netflix. He is also 100 percent correct to note that Netflix’s data and Nielsen ratings are two very different measurements and shouldn’t be used to compare shows. Landgraf is similarly right to suspect that Netflix puts out numbers that paint its shows in the best possible light, because of course they do. (As Landgraf himself noted Monday, “Networks have been touting their successes forever,” while working equally hard to play down their failures.) Netflix absolutely benefits from the perception that it has a ton of must-watch shows: It drives folks to sign up for the service and helps convince current subscribers to stay. And as others have noted, Netflix also wants creators and actors to know that people are watching Netflix shows because, as important as money is to creative talent, knowing their work is being seen is not an insignificant motivation for what they do for a living.

But Landgraf’s case gets weaker when he all but accuses Netflix of being a con artist deliberately trying to mislead the media, and, by extension, everyone else. Consider how he characterized Netflix’s release of the numbers for You and Sex Education. After accurately quoting Netflix’s shareholder letter announcing the 40 million figure for You, Landgraf made it seem as if the streamer was trying to pull a fast one on reporters and shareholders: “Subsequently, Netflix clarified the statement by adding that their watch time meant that an individual Netflix account watched at least 70 percent of one of You’s ten episodes,” he told reporters. A Netflix rep declined to comment on Landgraf’s charges, but in fact, Netflix offered that important qualifier in the very same shareholder letter in which it revealed its 40 million number.

Further, even as Landgraf accurately noted that the “ratings” released by Netflix are not comparable with the Nielsen numbers regularly reported on by American media outlets (including Vulture), he then threw out his own set of misleading numbers. Citing Nielsen’s Subscription Video on Demand Content Ratings, the FX chief claimed that the average U.S. audience for You on Netflix was closer to 8 million viewers during its first month, while Sex Education had just over 3 million viewers in the States. While Nielsen is obviously a reputable and respectable company — it’s long been the gold standard for audience measurement in the U.S. — its SVOD ratings simply don’t capture all of Netflix’s actual audience. They don’t count the not-insignificant number of Netflix members who stream via mobile devices or on their computers, and more importantly, they only measure American viewers. Netflix has more international subscribers than domestic, making any measurement that counts only U.S. eyeballs inherently incomplete. To be sure, Landgraf did specifically say “U.S. viewers” when citing the Nielsen Netflix numbers. But it’s pretty ironic that after accusing Netflix of trying to confuse shareholders and the media with misleading data, Landgraf arguably did the same thing on Monday. The result: Multiple industry trade publications and at least one major daily newspaper reported the 8 million and 3 million figures thrown out by Landgraf without noting that those figures don’t include non-U.S. viewers.

Look, when Netflix characterizes the You audience by saying the show “will be watched by 40 million member households,” it’s definitely not telling the whole truth about a show’s actual performance. But it’s also not engaging in unprecedented smoke-and-mirrors shenanigans, as Landgraf suggests. Instead, Netflix is offering the sort of bumper-sticker distillation networks use all the time to hype their performance. Just yesterday, CBS put out a press release noting that 149 million people had seen “all or part” of the Super Bowl, even though its average audience (also reported by the network in its release) was just over 100 million. Shady? Maybe! But networks use that bigger number because it gets across the message that lots of people are engaging with and sampling a show. Similarly, Netflix’s grossly simplified numbers, as Vulture reported when they were first released, are “best understood as a reflection of whether a show is getting sampled vs. being enthusiastically consumed.” The fact that Netflix doesn’t spell this out in bold letters clearly irks Landgraf, and that’s understandable. The streamer is never going to win any awards for data transparency, and Landgraf is right to note that Netflix benefits from casual observers when comparing its 40 million figure with numbers that get reported by Nielsen. Landgraf benefited from the same dynamic Monday when he tossed out his glass-half-empty assessment of the audiences for You and Sex Education.

But it’s not Netflix’s job to convey nuance and context when reporting its audience statistics. That’s the job of journalists. And much (though not all) of the reporting last month on Netflix’s sudden data dump did put those stats into proper context, often including a healthy dose of skepticism about them. As much as Landgraf would like to make it seem as if Netflix’s PR spin goes unchallenged, there’s been lots of good reporting in major publications that relayed the data Netflix offered with the proper big-picture perspective. Less praiseworthy: the flood of headlines and tweets that reduced the information Netflix released to “40 million people watched You on Netflix.” But this is a problem that applies across the board these days, not just with Netflix. Likewise, those of us who cover TV need to avoid playing into the narrative that just because a show is successful for Netflix doesn’t mean it’s some sort of massive game changer that represents a new paradigm for the TV industry. The Big Bang Theory gets over 17 million viewers every week, but you don’t see a hundred stories about how CBS is reinventing TV comedy each time Nielsen releases numbers for the show.

As part of his latest Netflix sermon, Landgraf also got worked up about the perception that Netflix is some sort of hit factory. Because it keeps most of its audience data locked away from public view, he argued, Netflix creates an illusion of success it doesn’t deserve. While a show like Stranger Things is a legit success, “Netflix has also made and launched a multitude of consumer failures,” the FX boss said. “But by … failing to ever report a single strikeout, they undercut an accurate perception of their batting average and misrepresent the number and scale of their hits. And that perhaps is the point. By creating a myth that they’ve used data to find the magic bullet — guaranteed commercial success — that has eluded everyone else since the creation of television, they’ve given the impression that the vast majority of shows on their platform are working.”

Landgraf is right that Netflix has not released audience numbers for its unsuccessful shows. One of the advantages for showrunners who bring their wares to a streaming service is that there’s no daily report card, no embarrassing stories about a series generating a “record low rating.” (Megaproducer Ryan Murphy, who’s made some of FX’s biggest shows, cited this as one of the reasons he defected to the streamer in 2018: “It’s been a daily death having to get up in the morning and get your daily report card that you know is a lie,” he told me last year.) But it seems myopic at best — and disingenuous at worst — to argue that Netflix doesn’t report its failures. Every time it cancels a show after one season, Netflix is admitting that it launched a flop. When the service canceled Michelle Wolf and Joel McHale’s talk shows on the same day, it endured a social-media backlash for days, and a round of stories questioning its decision to get into the weekly talk-show game.

No doubt Netflix renews plenty of programs that don’t get “big” audience tune-in, but Landgraf shouldn’t be complaining about this, either. He knows full well that Netflix’s business model isn’t about aggregating the most number of eyeballs for individual shows, but rather adding and retaining subscribers and driving more hours of overall viewing. Similarly, FX Networks has long supported shows with so-so ratings (from The Americans to You’re the Worst) because, in addition to ad revenue, it relies on getting cable operators to pay it more in subscriber fees. The more FX and FXX have been seen as among the best networks on TV, the more they’ve been able to charge cable companies. Netflix benefits from the same sort of virtuous cycle. It’s no doubt annoying to Landgraf that a number of Netflix shows with middling or even small audiences get labeled as “hits” by reporters simply because they keep getting renewed or get a lot of tweets. But there are folks at NBC who no doubt chafe every time The Good Place is called a “low-rated comedy” while FX’s Atlanta — with a substantially smaller audience — is painted as a hit.

To be clear, much of what Landgraf said to reporters on Monday was rooted in legitimate grievances. Netflix does get treated differently than traditional linear networks and benefits greatly from being able to hide basic facts about how its content is consumed by audiences. As someone who’s been covering TV ratings for 25 years, I would love nothing more than to know exactly how Netflix subscribers watch (or don’t watch) particular shows. But Netflix’s ability to make a whole bunch of good-to-great shows available to hundreds of millions of people at a reasonable price without the tyranny of overnight ratings is a good thing for consumers and creatives. And while Landgraf — one of the most intelligent and thoughtful execs in Hollywood — is rightly concerned about Netflix getting too big and having too much control over what audiences see, the way to counter that very real problem is not to insist on exposing the streamer’s hidden ratings data. It’s for other big media companies to invest heavily in creating their own streaming rivals to Netflix. Landgraf is aware of this, of course. Once Disney completes its purchase of 21st Century Fox, FX will become a part of Disney, which later this year will launch a new streaming service designed to take on Netflix directly. Here’s a prediction: That new service won’t release much ratings information, either.

This story has been updated to show that while Nielsen uses comparable methodology in its linear and SVOD ratings, its ratings for Netflix don’t measure all of the streaming platform’s audience.