The 2019 Conference of the Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP), which ends today in Portland, OR — a town equally endowed with bookstores and breweries — capped off its opening day, Thursday, as it always does: By forcing attendees to choose between social revelry and an hour-plus late-evening keynote address.

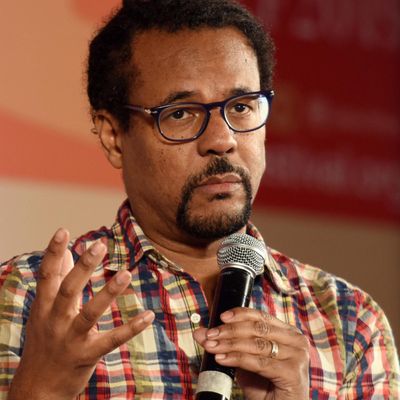

Considering the boozy alternatives, a conference keynote speech can sometimes feel like filing into a great hall to eat your peas. But this year’s AWP honoree, Colson Whitehead, chose to focus instead on chicken.

Returning again and again to the metaphor of cooking endless arrays of fried chicken (and returning most often to the recipes of David Chang), the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist delivered a characteristically sprawling and idiosyncratic speech encompassing alternate universes, revenge fantasies, Star Wars, college students, and cultural appropriation. He also reimagined “This Is Just to Say” as written by an older, crankier William Carlos Williams:

Yeah, I ate

the plums

Go fuck

yourself.

No one dozed during this speech and almost no one ducked out early. The chicken shtick may not have been for everyone, but it sure as hell wasn’t dry.

Below, a primer on writing, life, and exquisitely spiced poultry according to Whitehead, whose forthcoming novel, The Nickel Boys, comes out in June, and whose dinner parties must be amazing.

“There’s only two kinds of food: food you like, and food you don’t like.”

Whitehead, whose novels straddle satire, horror, humor, alternate history, speculative fiction, and literary fiction (whatever that means), doesn’t really believe in any of these categories. “Are we really still talking about all this crap?” he asked. (Less and less, but it’s still fair to ask.) “There’s only two kinds of books, shit you like, and shit you don’t like.” Any author worth their salt is going to borrow and mix ingredients from all of their influences; instead of worrying about how or where their work will be received, “You might as well make food that turns you on.”

“Don’t worry about reading other people’s great works. Find your own.”

At one point Whitehead referenced W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, then asked how many people in the crowd had read it, to scattered applause. “You guys haven’t read Rings of Saturn?” he said in mock-reproach. But seriously: “Don’t let anybody make you feel dumb because you haven’t read something. You can still lead a long and fulfilling life.” Curate your own personal library of classics. You’ll get to the “required” reading in good time — when you’re ready for it.

“Someone more talented than you has done it, so you might as well forget it and trust your own uniqueness.”

When he set out to write The Underground Railroad, Whitehead wanted to reread authors like Toni Morrison and Edward P. Jones — to borrow some ingredients. Twenty pages into Morrison, he felt paralyzed and defeated. How could he ever top this? Of course, he couldn’t. But instead of trying to outshine the greats, Whitehead accepted that he wasn’t better — just different. He could still put his own spin on a slave story, and write the book that only he was qualified to write.

“Read and read to find out what kind of writer you want to be. Write and write to find out what kind of writer you are.”

Whitehead described himself as a mediocre creative-writing professor who “knows his place in the ecosystem” and “props up a lot of people” at AWP (a conference dominated by MFA programs) with his own middling performance. But how many teachers can craft a writing lecture out of fried-chicken recipes and deliver pedagogical koans as powerful as the above? It was the crystallization of the real subject of his speech: Set your expectations high, and meet your heroes in the middle, somewhere between your limitations and your dreams.

“Write what you don’t know.”

“Write What You Know” is on the greatest-hits album of MFA clichés, along with “Kill Your Darlings” and “Show, Don’t Tell.” The result? A rash of muted New Yorker stories about suburban adultery. (Note: This opinion is mine, not his.) Whitehead advocated the opposite: “Tackle a story that you’re scared to begin, that you don’t know if you can pull off.” (Something like, say, a novel about zombies in New York, a.k.a Whitehead’s Zone One.) A writing workshop — like any other room with people in it — is a “laboratory of failure.” Expect failure on the way to success.

“If it tastes like shit, it’s cultural appropriation.”

Back to that chicken: Whitehead knew the stakes were high when he tried to whip up Korean fried chicken; if he failed, he was a cultural appropriator. On the other hand, “No one’s gonna call you out if you pull it off. No one’s coming for Bill Shakespeare, because he didn’t fuck Othello up.” (Well, some people have.) It’s risky to cook up something you didn’t grow up making — to push boundaries and genres, or embody a character who is totally alien to yourself. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try. “You can write about anything,” Whitehead said. “Just don’t fuck it up.”