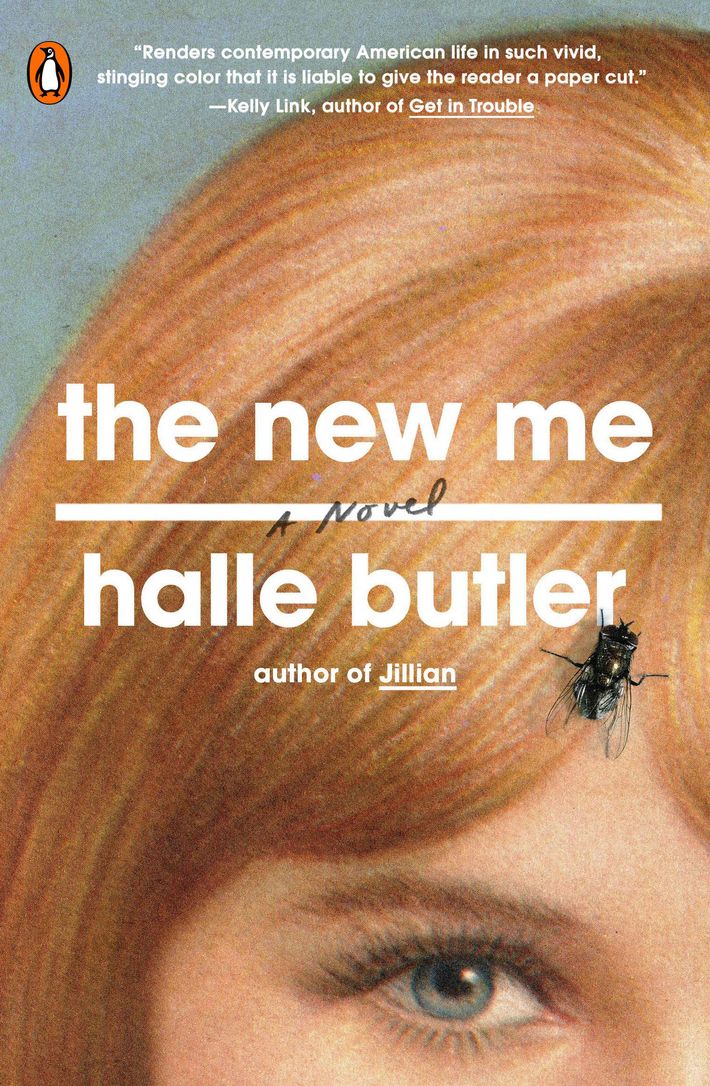

The first thing we learn about thirty-year-old Millie, the protagonist of Halle Butler’s incisive and lean second novel, The New Me, is that her “pits are slick” and her face “smells like a bagel.” In the next scene, she stands on a crowded train during her morning commute: there’s “aimless bile” at the back of her throat and a hole in her underwear “from scratching too much.” Her apartment has a consistently bad odor: “part dirty clothing, part cooking oil, part garbage,” and then, perhaps to cover it up, “part incense.” Millie’s life wafts off the page like cartoon stink squiggles. As Millie’s boss notes, “Looking at her evoked a kind of smell.”

She’s a perfectly miserable temp at Lisa Hopper, a mass-market furniture showroom run by overconfident 20-somethings. Her life isn’t in disarray or free fall; it’s simply a void — of friends, of love, of a career, of willpower. The novel is a graph of Millie’s lifewide bradycardia; the needle barely moves even as she hatches plots to turn her fortunes around. “I should get some exercise, I should unclench my muscles, I should get a hobby,” she thinks. “I should figure out why no one wants to be around me … I should get a cat or a plant or some nice lotion or some Whitestrips, start using a laundry service, start taking myself both more and less seriously.” None of that happens.

The New Me, out this month from Penguin, joins a growing list of novels that are the yin to the yang of Instagram and vlogger culture. There is the army of polished beauty bloggers narrating 13-step serum and Beautyblender routines, who scrub and paraffin and lotion their bodies into sterile, poreless expanses, and then there’s Millie, whose crotch stinks and who doesn’t even brush her teeth, let alone whiten them. College-scamming influencers hector you to keep your life together, your space smelling like cedar and moss, your cheekbones contoured, and your armpits naturally deodorized with baking soda and cornstarch. But in literature there’s a perversely refreshing counteroffensive of odiferous refuseniks, a burgeoning genre you could call Repulsive Realism.

The pioneer and reigning queen of this trendlet is Ottessa Moshfegh. The titular narrator of her breakout 2015 novel, Eileen, is a sloppy, occasionally vomit-covered secretary at a boys’ correctional facility who lives with her drunk of a father and wears her dead mother’s unflattering, unwashed clothes. She revels in her contempt of the conventions of common decency, describing herself as “easily roused by the grosser habits of the human body.” Eileen’s particular body is a constant source of liquids and gasses; she is a walking incarnation of the ancient Greek “four humors”: blood, black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm. She’s a laxative addict, and her shits are “torrential, oceanic, as though all of my insides had melted and were now gushing out.” She adds, “Those were the good times.”

The grime makes Eileen who she is, a young woman who keeps a dead field mouse in her father’s old Dodge truck and occasionally peeks at its decomposing body (it’s a “good luck charm”). Every space she inhabits reeks — her laundry of “something like sour milk, sweet and laced so strongly with the perfume of gin” that it turns her stomach; her truck of errant exhaust; the correctional facility of “the noxious aroma of fish.” Unlike Millie, Eileen takes pleasure in the rebellion of her grease and stench.

After her protagonist made some critics queasy, Moshfegh told The Guardian that Eileen “is not perverse. I think she’s totally normal … I haven’t written a freak character; I’ve written an honest character.” That may be a stretch, but it’s true that Eileen simply doesn’t play the game of femininity, especially as it was played in 1964, when the novel is set. “I got an itch in my underwear,” she explains, “and since there was nobody to see me, I stuck my hand up my skirt to get at it. As swaddled as they were, my nether regions were difficult to scratch. So I had to dig my hand down the front of my skirt, under the girdle …” The feminist symbolism is clear.

Moshfegh’s interest in the disgusting body persisted in her next novel, 2018’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation. Unlike Eileen — a latter-day Jane Eyre, “poor, obscure, plain and little” — the unnamed narrator of My Year is beautiful and knows it. But on her quest to sleep for a year — the epitome of opting out — the narrator also abandons the normative grooming habits of a modern New Yorker. “I took a shower once a week at most,” she says. “I stopped tweezing, stopped bleaching, stopped waxing, stopped brushing my hair. No moisturizing or exfoliating. No shaving.”

Her subconscious, however, can’t stop shopping and scrubbing. After days of sleep she finds that she’s had a bikini wax while slumbering. Yet filth invades her dreams (“I dreamt I stole somebody’s diaphragm and put it in my mouth before giving my doorman a blowjob”) and eventually her bed. She wakes up to “popsicle sticks on my pillow, orange and bright green stains on my sheets, half a huge sour pickle, empty bags of barbecue-flavor potato chips,” and more. Untether the mind, and the body will follow.

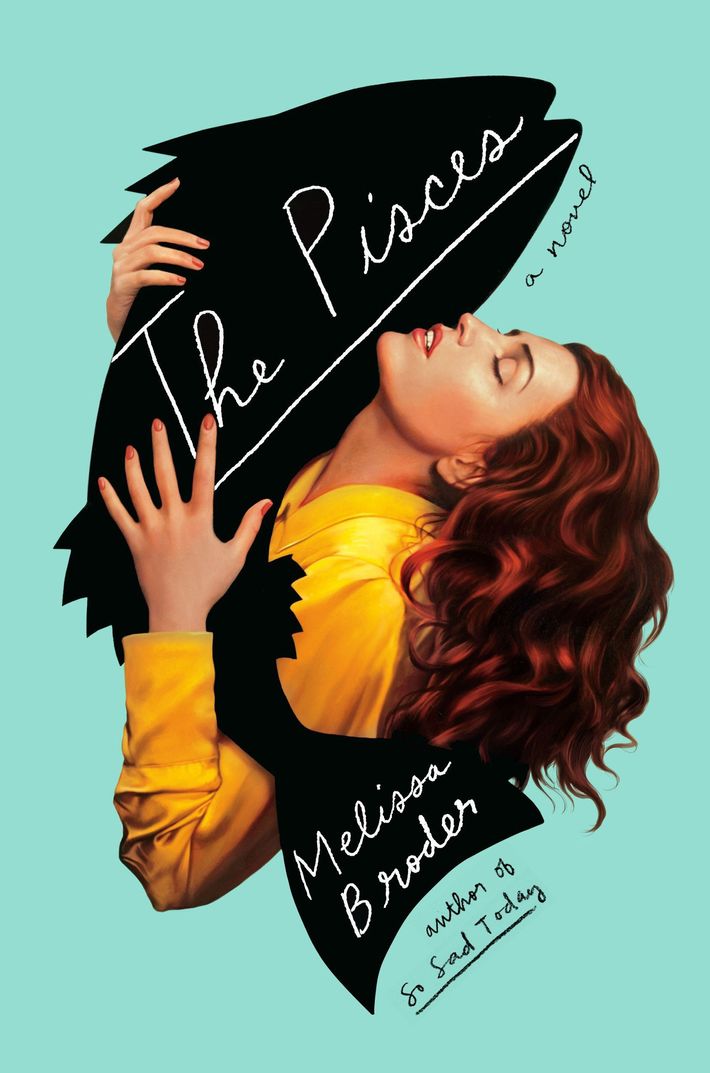

Repulsive realism comes in other varieties. In Melissa Broder’s The Pisces — a lust story about Lucy, a depressed Ph.D. candidate studying Sappho, and the merman she meets on the rocks near Venice Beach — sex is inseparable from disgust. In preparation for a date, Lucy gets a wax; the waxer depilates her anus, telling her she’s been “carrying around stink.” Her date’s apartment is covered in “stains that looked like spaghetti sauce, tar, and generally a lot of lint.” The sex itself is “disappointing and gross”: His penis is “pink and slimy” with “mismatched brown balls.” Before her next date, Lucy tries on lingerie and imagines “other women’s vaginal juices on the paper” inside the shop’s panties. Anticipating anal sex, she plunges her finger into her own ass to make sure there’s no “shit blocking his dick.” The ensuing chaos is like a bawdy Friends shtick, if Monica had discovered she could scrub out her anus.

It’s not that literature was antiseptic before Eileen came along (see: Upton Sinclair’s meat yards and Dickens’s factory floors). Raunchy sex and unwashed armpits aren’t new either. But today’s version isn’t about people attempting to rise out of the mud. Instead, the characters manufacture their own mire and swim around in it. They rebel against the packaging of femininity and the oppression of the lacquered image. The grossness is the point — much as it was when Joyce’s filthy Ulysses so irritated the aging Victorians (who we later discovered weren’t as precious as we thought), and D.H. Lawrence’s naughty women took lovers and discussed “the poor, insignificant, moist little penis.” Almost a century later, as Goop encourages women to steam clean their vaginas and grocery stores carry tonics that will detox our intestines and meant-to-be-shit-filled colons, is it any wonder that our protagonists are sniffing their own tangy, discharge-covered fingers?

We remember fondly the ways our favorite classic heroines were willing to get dirty — Elizabeth Bennet trouncing across a mucky field to visit a sickly Jane at Mr. Bingley’s country estate; Jane Eyre sleeping in a ditch rather than staying another night under Rochester’s roof. We may not exactly cheer Millie when she drags a leaking trash bag into the hall, or Eileen when she examines her own putrid shit, but we get a similar vicarious charge of liberation. We begin habituating ourselves to the notion that odor and grunge aren’t abnormal or perverse. They’ve simply been glossed over by potions and filters for so long that we’ve almost forgotten they exist.