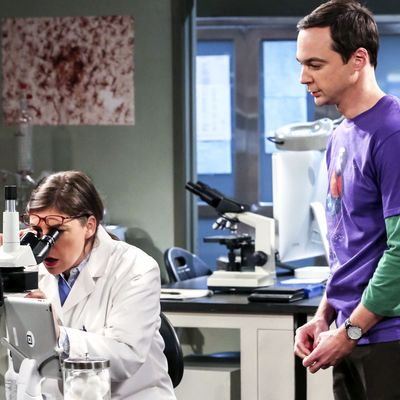

The Big Bang Theory, a sitcom about smart people not being able to eat food correctly, will conclude next month after a tremendously successful 12-season run. But if you’ve only tuned in to the final season on a casual basis, you might not even realize it was ending, as the show has generally eschewed big narrative wrap-ups except for one development: The married theorist team of Sheldon (Jim Parsons) and Amy (Mayim Bialik) are in contention to win a Nobel Prize in physics for their discoveries within super asymmetry. However, a couple of experimental scientist punks (played by Sean Astin and Kal Penn) are trying to claim the Nobel as their own for accidentally proving the concept, and since at present only three people can receive a Nobel for a discovery, only one of the pairs will be able to call themselves winners.

Since Vulture is a pop-culture website and not, uh, a string-theory website, we have absolutely no place offering expertise about which duo should be the rightful recipient of the prize. So we did the only reasonable thing we could think of: Reach out to a bunch of actual Nobel physics laureates and ask for their very legit, very respected, very intelligent opinions on the subject. Knowing our inquiry was all in good fun, seven laureates were nice enough to weigh in on television’s hottest STEM showdown. Here’s what they had to say when it came down to a theorists vs. scientists debate.

Robert Laughlin (1998, for the explanation of the fractional quantum Hall effect)

“The prosaic answer is that first to print gets the honor. There are notorious cases in which this metric has been complicated — notably the discovery of asymptotic freedom — but this is the only metric we have that is fully witnessed, so it’s the one we have to use. This is one of the reasons worthy scientists working for companies often get passed by. They can’t publish! So the correct answer for The Big Bang Theory is whoever published first.

The somewhat lighter answer is that it’s hard to take sides because the show is true. Nobody could make all of that stuff up! It actually happens in real life, trust me, right down to specific discussions people have and specific words they use in them. I always found the show so true to life that it was hard to watch. My wife became completely addicted to it. She was married to one, you see, so she could see way more humor in the show than everybody else could. So the show isn’t really ending! It will live forever in little corners of the world such as the one I inhabit.”

Frank Wilczek (2004, for the discovery of asymptotic freedom in the theory of the strong interaction)

“I’m not a fan of The Big Bang Theory, but evidently it’s raising legitimate issues of public interest. A big reason why the Nobel Prize in Physics is so esteemed is that the process where candidates are nominated and assessed is taken very seriously by the international physics community. A lot of thought, and work, goes into it! While there are surely gray areas and ‘high politics,’ there’s an overwhelming consensus that the prize is almost always awarded appropriately. So I don’t think the show’s premise — that the nominations received from a couple of administrators could decisively affect the process — is at all realistic. A scenario where a surprising experimental discovery of a fundamentally new physical phenomenon could get a quick Nobel Prize isn’t crazy. It’s happened several times. But if a discovery is truly surprising, then it takes time to reach a consensus on the theoretical interpretation, even if the correct interpretation is already out there.

The simple and plausible solution of the problem posed in the show would be that the experiment would get a Nobel Prize promptly, with a separate theoretical Nobel Prize coming later. In viewing past mistakes and criticism, the [Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which awards the Nobel Prize in Physics] is now acutely sensitized to issues of squeezing out women or worthy junior collaborators. There’s no way that would happen just because some lab director or university president suggested it.”

John C. Mather (2006, for the discovery of the blackbody form and anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation)

“I could well imagine that the Nobel Committees have had to answer the same questions for real. I think historically the Nobel Committees have preferred experimental results to theoretical ones. Sometimes it’s very hard to assign credit for a theoretical discovery, since it may come out of a conversation, or it may happen very quickly, or it may happen at a time when many people are working on the same question. Theorists quite often work on dozens or hundreds of fascinating problems, and get lucky that some of them turn out to be both right and important. Sometimes it’s very hard to assign credit for an experimental discovery, too. Most big discoveries these days require teams of people, sometimes thousands, as in the detection of the Higgs boson. Who in such a large team deserves credit? It would take intimate knowledge to really know.

In the case of Sheldon and Amy, they are the ones who know the best. In Einstein’s case, many people are still discussing the contributions of his wife, who did not share the prize, but received all the money in her divorce agreement. I also note that people trying to get the prize can be tempted to behave very badly; I’ve often thought of Frodo Baggins and the ring. So Sheldon and Amy are not the only ones with a problem!”

George Smoot (2006, for the discovery of the blackbody form and anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation)

“The credit and awards would depend upon the level of the theory, the proof, and discovery. For example, occasionally in the prediction of a new theory of a new particle, the prize could be given both for the discovery of the particle and for the theory. But there are other cases where the theory is less of a total impact when the discovery or observation got the prize.

The show has gotten to a point where we haven’t had a clear discussion of what the incredible overarching importance of super asymmetry is. One might assume it’s a really big deal and a monumental achievement by Amy and Sheldon. However, in reality, it’s really a plot vehicle more than anything to establish that Sheldon and Amy’s names will be remembered among the giant minds of physics, up there with Newton and Einstein. If that were the case, then they would be in line to get the prize. It does provide a way to show growth in Sheldon — to see if he’s appropriate to be a Nobel winner and set an example for young scientists and children. I had a lot of ideas along various story lines, and it’s not clear how the writers will handle this as being truly accurate to a real Nobel-laureate story.” [Editor’s note: Smoot has appeared on The Big Bang Theory twice this season as part of the super-asymmetry plot.]

Adam Riess (2011, for providing evidence that the expansion of the universe is accelerating)

“I think the Nobel Committee would try and determine who made the most critical contributions to the discovery. Assuming that there were still more than three, I think they would try and narrow the scope of what was discovered — so, not the whole discovery, but perhaps a part of it. At this point they might select one of the pairs and not the other depending on which they felt made the larger contribution, or whose discovery could be separated from the bigger picture. If that narrowing was not realistic — say all four people made a pretty similar contribution — then I believe they would just move on to another discovery. The Nobel does not promise to be a complete list of all important discoveries, so they won’t necessarily recognize every discovery. At some point in the future, one of the four might pass away, which could resolve the problem, too.”

Brian Schmidt (2011, for providing evidence that the expansion of the universe is accelerating)

“This is more or less a re-creation of the big-bang discovery in 1964. The challenge we have here is the convention that only three people can get the Nobel Prize, whereas clearly both Sheldon and Amy, as well as the experimentalists, deserve it. If we go on past form, the discoverers — which would be the experimentalists — get it. My personal preference is for everyone to share in the prize and break convention.”

Rainer Weiss (2017, for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves)

“It is clear that both groups should be candidates. One of the problems with things like the Nobel Prize, which has a limited number of recipients, is that is becoming less and less realistic. In an earlier day, new ideas and experiments might have been done by a small group of people, but now many of the most significant advances are made by large teams of people.”