Before it plunges us into its uniquely satirical hellscape, Richard Condon’s novel The Manchurian Candidate teases with an upbeat opening sentence: “It was sunny in San Francisco; a fabulous condition.” After which we delve into the tale of a brainwashed Korean War veteran named Raymond Shaw, who is surrounded by power-mad politicians and duplicitous foreign agents and tasked by his own unscrupulous mother to carry out an epic political assassination.

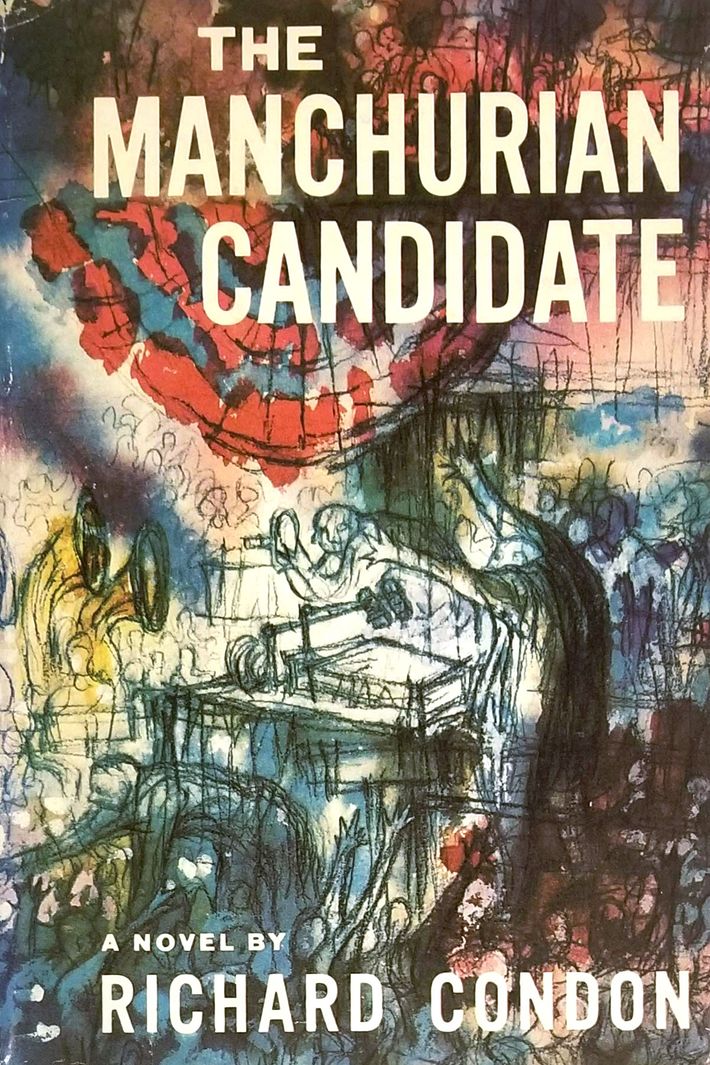

Sixty years ago, in April 1959, Condon’s second novel was loosed into a world beset by McCarthyism and Cold War paranoia. It was not exactly greeted as highbrow literature, but the reviews were generally good; Time put it on its list of Ten Best Bad Novels. It sold well enough, and its profile grew in the wake of John Frankenheimer’s 1962 film adaptation, which itself took roughly 25 years to find a lasting audience, perhaps having something to do with the assassination of JFK. In the years since, the story has undergone the occasional reboot: John Lahr’s 1994 stage play, Jonathan Demme’s anodyne 2004 Gulf War–era remake, even a 2015 operatic adaptation. But over time, Condon’s novel has taken a back seat to Frankenheimer’s film and been largely relegated to the shelves of used bookstores like the one I wandered into on a rainy afternoon in San Francisco earlier this year.

I bought the book mostly as a curiosity. The title, The Manchurian Candidate, invoked since Trump’s election by columnists and cable-news jesters of both left and right, had been echoing like an air-raid siren in my head for more than two years during the buildup to the Mueller report. I was expecting to encounter a dated pulp novel larded with camp, and I wasn’t entirely wrong. But what I also discovered in those pages — and in Condon’s worldview — was something that, while originally targeted at the barbarities of McCarthyism, felt like a pitch-perfect anticipation of our current national mood.

It took some time to adjust to Condon’s prose; it is, as Louis Menand wrote in a 2003 New Yorker appraisal, a deeply strange book with wildly shifting tones, odd word choices, and often baffling metaphors (some of that may have been by design; one blogger found that Condon appeared to have cribbed certain phrases from Robert Graves’s I, Claudius). The Times, in its initial review, called it “a wild, vigorous, curiously readable melange.” But the further I got into it, the more I began to think that Condon, in his messy way, had tapped into something bigger.

This was not just a book that presaged the Zeitgeist because it was about an enemy manipulating our political system — though that part, particularly early scenes that feature a Chinese psychiatrist demonstrating his brainwashing techniques on Shaw, did feel weirdly resonant. What struck me more was how, six decades ago, Condon’s style adumbrated the creeping sense of absurdity that so many of us cope with on a daily basis: that feeling you have when you wake up every morning and you think, How indescribably idiotic is the world going to get today? That’s the space Condon inhabits; it was the driving force behind his over-the-top writing.

Consider this simile from The Manchurian Candidate describing what it feels like to be the subject of a British tabloid report: It was “not unlike falling nude into a morass of itching powder while two sadistic dentists drilled into one’s teeth at the instant of apogee of alcoholic history’s most profligate hang-over.” That’s a ridiculously overwritten sentence; just to retype it makes me feel like I’m going to get scolded by an MFA professor. But we live in a moment where no metaphor or form of satire is big enough to contain what’s actually happening. The antic use of ten-dollar words here feels somehow apposite.

All that wild language was a reflection of Condon’s central belief: that the world has always been batshit-crazy and inherently corrupt. “He really felt there were conspiracies at work all the time,” his daughter, Wendy Jackson, tells me. “To him, it was a prevalent feature of our society.”

Where Condon’s relentlessly cynical view of America came from is not entirely clear; while he saw sinister plots everywhere, he was anything but a sinister person, says his daughter. But there are hints in old interviews about the roots of his disillusionment. A difficult childhood in early-20th-century New York City and an overbearing father left him with an occasional stutter; a nearly two-decade career as a Hollywood press agent made him entirely disdainful of both movie stars and the people who worshipped them. In dealing with moguls like Cecil B. DeMille and Howard Hughes, he grew increasingly skeptical of America’s obsession with wealth and power. At one point, a co-worker at RKO Pictures showed him the machine Hughes used to listen in on his employees’ telephone calls.

“After 22 years of lifting actors and producers off bored whores at Polly Adler’s, bribing the press and doing the 50 other useless things that are a part of that work, you do tend to get a little anti-authoritarian,” Condon told one interviewer. “You lose respect for public judgment because you know you can sell them anything. An-y-thing!”

Virtually every major character in The Manchurian Candidate — and, as far as I can tell, every character in Condon’s oeuvre — is an obsessive misanthrope, including Raymond Shaw, who resents nearly everyone around him. As for the rest of the cast, some, like Shaw’s heroin-addicted mother, Eleanor, are Machiavellian; others, like Shaw’s McCarthyite stepfather, Senator John Iselin, are mere useful idiots. Sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference between those who are doing the conditioning and those who are being conditioned. People plot, scheme, and give long and windy backroom soliloquies about returning America to its “original purity.” There’s a running joke in the book (and also in the movie) about how Senator Iselin repeatedly alters the number of communists he purports to have found in the Defense Department because he’s too simpleminded to remember. (Iselin is obviously modeled on Joseph McCarthy, but he’s essentially a proxy for every made-for-TV politician who’s emerged in the years since.) Eleanor finally tells him to settle on 57, because it “could be linked so easily with the fifty-seven varieties of canned food that had been advertised so well and so steadily for so many years.”

All of which coheres into something more than just a book about a politician compromised by foreign influence; it is a book about a compromised country. In The Manchurian Candidate’s dystopia, all of our institutions are broken. Every societal check or balance is manipulated by the people at the top, and the masses are either too distracted or too complacent to care. But even as the media — including Raymond himself, who ascends to a job as a political columnist after being brainwashed into murdering his predecessor — bellows out warnings, no one cares. “The Republic was a humbug, the electorate rabble,” Condon writes in the voice of Eleanor (who was reportedly based on lawyer Roy Cohn, the direct link between McCarthy and Donald Trump), “and anyone strong who knew how to maneuver could have all the power and glory that the richest and most naive democracy in the world could bestow.”

Condon published more than two dozen books over the course of his career, including a series of novels about a hit man named Prizzi, one of which John Huston adapted into Prizzi’s Honor, the 1985 film that won Huston’s daughter Angelica the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. He also wrote ambitious historical works. But it’s the political stories that offer the most intense distillation of his worldview. They’re ridiculous and they’re fun in their relentless mistrust of institutions and their outrage at the ways in which we’ve been brainwashed by those with the means and the power to do so. In 1974’s Winter Kills, a rollicking, strange JFK-assassination conspiracy novel — later made into a 1979 William Richert–directed black comedy — a rich patriarch boasts about how owning hospitals is the ultimate business opportunity: “No credit for the customers, and they pay in advance or out on their ass.”

Condon once described his depictions of America as deliberately “baroque” and “grotesque,” but his imagined conversations between power brokers behind closed doors are the routine discourse of the Trump era. Such is the moment we live in.