This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Every month now, a notable brand goes viral for tweeting something provocative, absurd, or entertaining. Advertising has always been integrated with culture — mascots brought brands to life, influencers became human billboards — but Twitter has facilitated a new sort of intimacy for brands, one in which they can blend in with people and develop their own personas. Unlike commercials on Hulu or promoted posts on Facebook, a user might respond to a brand’s tweet without consciously thinking it’s an ad. Four months later, it’s in some marketer’s PowerPoint about #engagement and #authenticity.

In the beginning, Brand Twitter lagged behind internet culture. It was known most for its “fails” and ethical gray areas. But as marketers started hiring people who were Extremely Online, it caught up. Tweets became more self-aware and ironic, which led to increased visibility as well as criticism. (As the writer behind one brand account, I’ve experienced both.) Nothing drives positive engagement quite like humor, so the more successful brands co-opted comedic styles from various subcultures over the years. Which, in turn, led to more fails and ethical gray areas.

Here, we bring you the definitive history and evolution of Brand Twitter.

2007–12: The Early Years of Brand Twitter

Only a handful of moments from the first years of Twitter have stood the test of time like the Chargers–PF Changs saga of 2007, in which the (then San Diego) Chargers account sent out a classic 2007 tweet:

What actually happened was its digital-media person previously owned the @Chargers handle, so once the team acquired it, it came with his old tweets. This is now an artifact of Brand Twitter history.

Aside from the Chargers, most prominent brands didn’t join Twitter until 2009. (To sum up 2008: Mommy bloggers brought down a campaign by Motrin that implied some moms wear babies as fashion accessories, people began questioning whether brands should be allowed on Twitter, and JetBlue tapped into the furry community.) Some failed off the bat — see Domino’s first tweet, which was about how it fired two of its employees who messed with customers’ food after the story went viral. As YouTuber Jarvis Johnson pointed out, other brands immediately personified themselves:

Between 2009 and 2010, Brand Twitter became enough of a thing that a meme was born: blaming mistakes on rogue interns. If you were a brand on Twitter, you were likely known for making a misstep. More notable fails continued into 2011. “Who’s #notguilty about eating all the tasty treats they want?!,” Entenmman’s tweeted, hopping on the hashtag #notguilty, which trended after the news of Casey Anthony going free. The peak fail of 2011 revolved around the Arab Spring, when the Egyptian government shut down the internet. The story trended, and Kenneth Cole opportunistically jumped in: “Million are in uproar in #Cairo. Rumor is they heard our new spring collection is now available online at http://bit.ly/KCairo - KC.”

Later that year, a new trend emerged: the viral clapback. The first came from Sega, which responded to YouTuber Justin Whang’s old handle @HotPikachuSex.

Brands noted the media attention, and in 2012, Old Spice and Taco Bell got in one of the first publicized scuffles, heralded by advertisers as avant-garde for the time, that popularized the trend of real-time marketing.

This trend continued with brands like Charmin and AMC Theatres, while others continued embarrassing themselves. Brand Twitter seemed so ridiculous, goofy, and easy to dismiss back then — until Denny’s showed up.

2013: Enter Player Denny’s

A few brands like Hamburger Helper had distinct personas by 2013, but none broke through the noise like Denny’s when it created its popular quirky-surreal-teen-blogger persona on Tumblr and moved it to Twitter soon after. Most of the credit for developing its presence goes to internet culture phenom Amber Discko, who combined all the right ingredients, such as diving into obscure subcultures and making jokes with the anime fan art of Potato Girl.

During these early years, most brands were still posting product shots, holiday greetings, or doing real-time marketing during events like the Super Bowl.

Denny’s distinguished itself and became one of the most recognizable social-media brands, with Forbes even crowning it the “King of Twitter.” It arguably kick-started the trend toward “weird corporate” personification by organically drawing in a digitally literate audience that chose to follow a brand for its consistently entertaining, relatable content.

Also in 2013, Tesco Mobile stood out for being one of the first brands to regularly roast people.

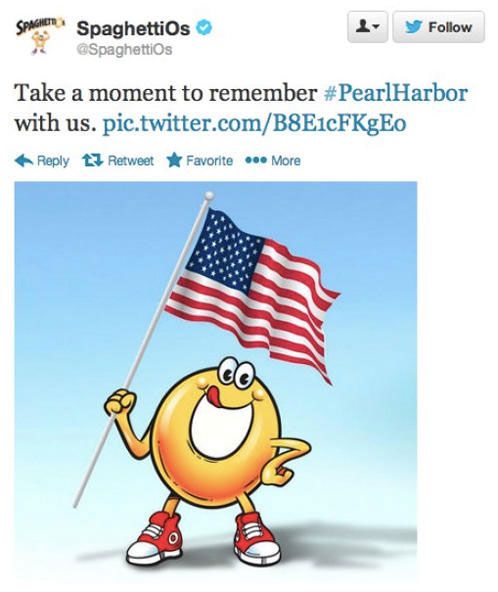

And what’s a year in Brand Twitter without mistakes? The ones in 2013 were quite memorable, like when Home Depot tweeted this racist picture or when SpaghettiO’s branded Pearl Harbor Day to sell noodle mush.

2014: The Year of “Bae,” “On Fleek,” and 9/11 Tweets

Twitter defined itself in 2014 by embracing images and cleaning up its interface, which led to more user and brand activity. When Brand Twitter was new, articles like “14 Times Brands Showed Their Sassy Side on Twitter” were everywhere, but now more people were raising their eyebrows at the tweets. Weird Twitter had long been trolling companies for hijacking its culture and leveraging it for profit, but once brands started using popular slang like “bae” and “on fleek,” mainstream criticism ramped up.

In August, the r/FellowKids subreddit became a hub to ridicule brands trying to be cool. It arrived just as things reached a boiling point the following month, when a number of companies published 9/11 tweets, including CVS, the Vitamin Shoppe, and Build-a-Bear. (Apparently, none had learned from AT&T’s disastrous tweet the year before.) Users universally piled on, and word spread across the web.

Most brands refrained from 9/11 posts after this, except the TV show Veggie Tales, which bravely took the leap again in 2017.

Corporate-watchdog account @BrandsSayingBae launched at the end of 2014 and began cataloguing all the most cringeworthy tweets from brands during this time.

The spotlight was getting hotter, and missteps were getting more consequential.

2015–16: Politics Centralize Twitter

Social media became central to users’ lives during the election cycle, so when something went viral like #TheDress, it trended universally. Because Twitter’s climate heated up and social-media managers had grown more savvy, brands started getting smarter about how to appeal to their audiences.

In 2015, Arby’s began producing artwork of (often obscure) games and anime out of restaurant items to differentiate its feed. This gave it clout among niche audiences that has continued to this day with its #MakeMySandwich campaign.

The tradition of mocking brands on social media continued. As Arby’s gained attention, the iconic brand-parody account, @NihilistArbys, was born at the end of 2015. “My perspective is ‘Hi. It’s me. The person in charge of the Arby’s account. I no longer care,’” the man behind the account, Brendan Kelly, tells Vulture. “‘I’m proving that, tweet by tweet. And I’m still fulfilling my duties as a corporate shill on Twitter.’”

In April 2016, Hamburger Helper … dropped a mixtape.

It was received so well the idea was copied by Wendy’s two years later and again in 2019 by the Chester Cheetah account, which dropped a diss track on Doritos. All of them went viral.

Once the election cycle turned up, brands began subtly (and not so subtly) dishing hot takes. Excedrin’s “debate headache” tweets were a fairly neutral way to cut through the noise.

Merriam-Webster dove into social justice in 2016 and developed an aggressive tone toward the right wing over the year anytime a controversial story broke. Dictionary.com hit a similar stride. This trend continues today, with more brands being bolder in their political stands.

Provocateurs like the Paul brothers learned to manipulate audiences during this time with outrageous stunts, inciting reactions and building personal brands through the outrage cycle. Shortly after, corporate brands discovered they could do the same.

It was the dawn of self-aware Brand Twitter.

2017: The Wendy’s Roast Heard Round the World

Brands had personified themselves for years, but the trend didn’t become an internet-wide meme until January 2017, when Wendy’s roasted someone who forgot refrigerators existed. The exchange exploded. Anderson Cooper even covered it on CNN. The roast-meister was Amy Brown, who left Wendy’s in March, partly owing to online harassment. Later that month, Wendy’s went viral again by roasting McDonald’s.

Then again in November. This became a recurring pastime.

Wendy’s had already cemented its Brand Twitter Queen status by April with #NuggsForCarter. A Twitter user named Carter Wilkerson tweeted at Wendy’s, “how many retweets for a year of free chicken nuggets?” Wendy’s replied, “18 Million.” It received 3.5 million retweets, the most of all time (until recently), and started the “How many retweets for (x)” trend. The Wendy’s social-media team even hosted an AMA on Reddit in December to cap the year. Companies took notes on upping the sass, like when DiGiorno dunked on Papa John’s during its NFL anthem-protest controversy, as well as Verizon getting into a BDSM battle with T-Mobile.

Another brand that caught its stride later in the year was Netflix.

Netflix is an anomaly for Brand Twitter. As the largest online streaming service with over 139 million subscribers, it boasts a massive reach with a digitally literate audience. It gets boosted by celebrity influencers who work with it as well as other popular accounts. Unlike fast-food restaurants, Netflix’s product is universally loved (except when it’s canceling shows or breaching privacy), and it’s constantly producing culturally relevant content that gets everybody talking. Like many brands, it tweets about its shows and movies in the voice of a witty millennial, but it’s also one of the only major corporations to use “fuck” in its tweets, so it plays by its own rules.

Netflix became one of the most popular accounts in 2018 with the help of movies like Bird Box, which became an internet-wide meme. People were watching the movie, then making memes of it, as well as seeing memes of it, then watching the movie.

Family-owned snack company MoonPie marked another evolution in Brand Twitter. It went viral in August when it threw shade at Hostess for claiming to be the official snack of the eclipse.

The brand could roast like Wendy’s and be absurd like Denny’s, but it was odd and wholesome, too. (MoonPie also opened a new can of worms by flirting with Wendy’s and best-friending Pop-Tarts.) Over the year, MoonPie was written about more than almost any other brand. “I think [this personified trend is] somewhat of a reaction to years of marketing experts screaming at their own industry for brands to be ‘More human! More real! More approachable!’” argues Patrick Wells, the creative–copywriter behind MoonPie’s Twitter voice.

In response to lagging behind the curve for so long, more and more brands hired internet-savvy people and comedians to improve their marketing, which swung the pendulum toward cultural relevance and relatability. The entire landscape was changing, and by 2018, this humanization became the norm. Just as these workers gained more freedom to be creative, many of them still bore the stigma of “just being an intern” doing a job that “anyone could do,” while also being on the front lines of online harassment.

“I think the biggest surprise people would have about Brand Twitter is learning that there are real people behind the accounts, reading the terrible shit you send, day in and day out,” Amy Brown says. “I can’t speak for other people working in this field, but when I was at Wendy’s, I regularly had to talk to my therapist about the replies I would read on our social channels. When you already have depression and you read enough times that you deserve to die, you start to really believe it. And the platforms care about abuse directed at a brand’s social-media manager(s) about as much as they care about abuse directed at an individual user. They’ve created an entire industry with no protections for the workers within it.”

2018: Mainstream Meme-ification and Humanization

If 2017 was the year Brand Twitter became memed, 2018 was the year it went mainstream. Users talked about brands like they were celebrities, admired their cleverness, embraced their absurdity, and even wanted to get roasted for fun. The impact of communities like r/FellowKids dwindled because brands were in on the joke and intentionally trying to get featured; it was like a badge of honor. Some brands, like Flex Seal, were even welcomed. Many of the top posts went from “this brand-posted cringe” to “this brand actually gets it.”

One account that stood out as exceptionally meta was dbrand, a skin company that the meme community embraced. Its feed has a similar vibe to Nihilist Arby’s, with blunt mantras like “Give us your money.” In May, a user insulted one of their memes:

It fired back with this deep-fried rendition, mocking a style found in places like 4chan or r/DankMemes.

Following Wendy’s viral success and the ongoing market for roasts, 2018 was chock-full of sass. In July, Pop-Tarts published a sentence unimaginable ten years ago.

Texas-based wing bar Pluckers gained attention after an exchange with controversial YouTuber Jake Paul in September. He asked for free wings; Pluckers blocked him.

Burger King’s U.K. account landed a massively popular roast by jabbing McDonald’s in the middle of a Kanye West Twitter rant.

In May, Roseanne Barr defended the racist tweet that got her show canceled by blaming a medication she was on made by Sanofi. The brand’s response was *chef’s kiss.*

When IHOP changed its name to IHOb to promote burgers, it sparked the most universally viral moment of Brand Twitter that year. A barrage of memes ridiculing the move followed; brands joined in, including Netflix, Wendy’s, and Whataburger.

Increasingly, dialogue tweets and joke formats that were ubiquitous on Joke Twitter were copied by platforms like FuckJerry as well as Brand Twitter. On the flip side, some companies formed online relationships with content creators when they shared their formats with consent. They also began frequenting comedic material that was unrelated to their brand.

As always, there were fails. The Buffalo Wild Wings account got hacked in June, posting vulgar, racist tweets. The Air Force compared air strikes in Afghanistan to the Yanny and Laurel meme. But most major controversies now centered on brands being (or not being) woke. Pepsi’s Kendall Jenner ad and Nike’s Colin Kaepernick ad both sparked debate over what role corporations should have in the culture wars — and now it extended to Brand Twitter too. Some instances were clear, while others more contested, such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium tweet that referred to an otter as “thicc,” a term originating in African-American vernacular English to reference black women’s bodies.

PETA was ridiculed for acting too woke when it tweeted this chart claiming people shouldn’t use “bigoted” phrases about animals. It resulted in a ratio so bad even vegans hated it.

Toward the end of 2018, Steak-umm ranted in a six-part tweetstorm touching on society’s problems in relation to Brand Twitter (Full disclosure: I’m the social-media manager for Steak-umm). The observations were both applauded and criticized for being covert advertising. This flagged another shift — brands making metacommentary as anti-marketing.

Brand humanization “works” now in part because people feel disconnected and disheartened after scrolling through the daily chaos. When a brand is entertaining or relatable, it opens the door to parasocial relationships, a.k.a. people viewing media personalities as friends. Brendan Kelly, the man behind Nihilist Arby’s, finds the trend troubling. “It’s the evolution of the matrix. That’s the way social media is going,” he says. “If we’re looking to brands on Twitter as a way to connect with humanity, then we’re irrevocably fractured as a society. They don’t love you. I would like to repeat that: They don’t love you.”

Critics also argue that this behavior can stifle criticism of brands. When Wendy’s roasts someone, everyone laughs, but when someone tweets “Wendy’s pay your tomato workers,” he’s the jerk ruining the fun.

2019: Brand Twitter Drives Off a Cliff

“Branding goes through cycles,” Brandon Rhoten, the CMO of Potbelly and former CMO of Wendy’s, tells Vulture. “Early days were all about features/benefits, then endorsements, then comedy, then genuineness, now absurdness. When brands all start sounding the same, it means we’re on the verge of the next step.” Brands took that next step in early 2019 by dipping into more controversial aspects of humanization, starting with SunnyD. During the Super Bowl, its account published this in reaction to how boring it was.

The tweet was memed, yet also interpreted as the brand (or social-media person) being depressed. Countless articles were written that week about brands going too far by exploiting mental health. Burger King followed suit with its #FeelYourWay campaign, promoting “Real Meals” (a jab at McDonald’s Happy Meals) and playing into the same narrative.

In the aftermath of all this, “Silence, Brand” memes surged. Users posted variations in response to anything brands tweeted for months as a tool to subvert their increasingly intrusive online presence, but as with everything, brands found a way to use it against them.

Some brands even began pretentiously lecturing their audiences. In April, Netflix Film told its followers to stop using the term “chick flick” because it’s problematic (woke brand critics jumped on it), and Chase Bank posted a now-deleted dialogue tweet telling people they were broke because they don’t budget (Twitter universally dunked on them).

Just when you thought What could possibly come next?, Vita Coco went where no brand had gone before. In response to someone tweeting, “I would rather drink your social media persons piss than coconut water,” they sent this. Yes, it’s real.

Users responded with shock … and respect.

So who knows what’s next? The internet is now an attention economy. Advertising is designed to misinform and blend in with culture. No one is immune. So stay sharp, and remember this: The arc of Brand Twitter is absurd, and it bends toward sales.