Technically, says Kristen Arnett, a taxidermied animal is a ravioli. This is not something she can spell out for anyone. “The entirety of the joke is to not have to explain why something is a ravioli,” she clarifies, referring to a 2017 internet meme that she has greatly improved upon in her highly amusing Twitter account. Suffice it to say that, like the best memes, it is both deeply existential and phenomenally silly. “If I have to explain to you why something is ravioli, then it’s not ravioli,” she continues, before explaining that this answer, too, is “technically a ravioli.”

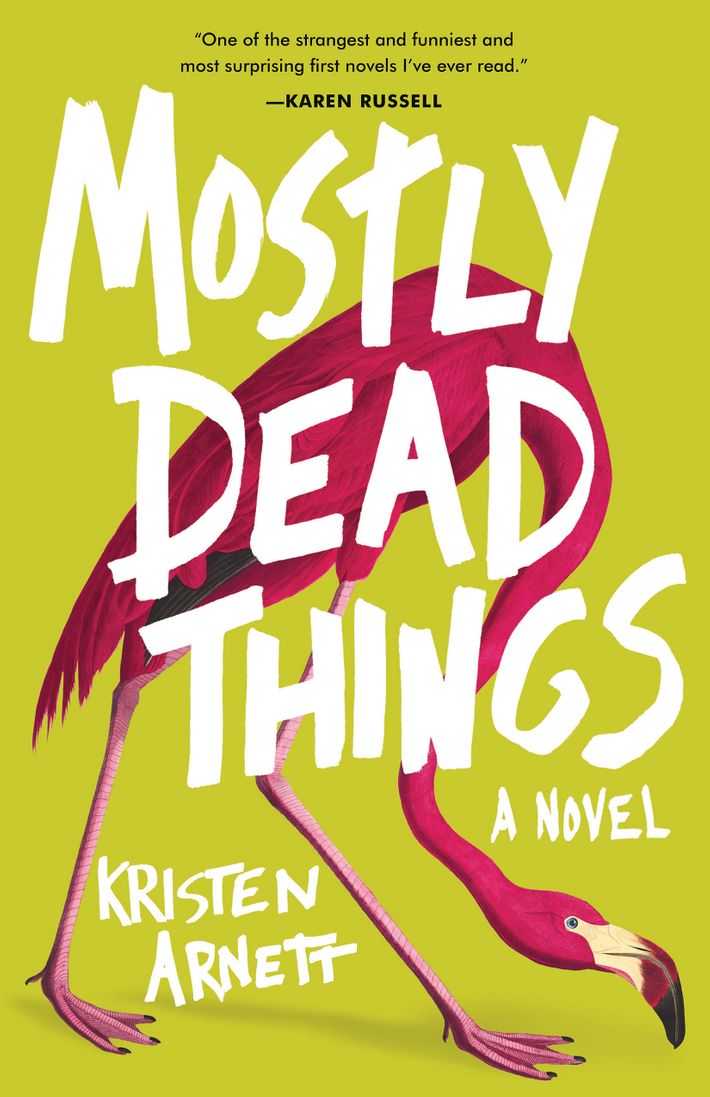

Arnett is many things to many people: meme master; 7-Eleven advocate; de facto cultural ambassador for Florida; Literary Hub’s favorite (and only) library columnist; and — by the way— also an essayist, short-story writer, and as of this month, the author of an acclaimed debut novel, Mostly Dead Things.

In person, Arnett pulls off a delicate balance that might be key to her very online success: tongue-in-cheek and fiercely clever but nonetheless as warm as the Sunshine State. She’s the kind of novelist whom, as they say, you want to get a beer with — and you could, if she’s not too busy “borrowing” her neighbor’s boat to eat Taco Bell out on a lake at 2 a.m. or befriending a local lizard. She’s also, like most librarians, remarkably patient, willing to “yes and” any and all questions, including, “Is a 7-Eleven like a library?”

She hedges before saying, “Well, actually, maybe! How many times has my 7-Eleven cashier had to figure out the riddle of what someone’s asking them? Fuck, maybe a 7-Eleven is a library!” Her local 7-Eleven, in the Orlando area, was the site of her first book launch, for the debut fiction collection Felt in the Jaw. “I read next to the Slurpee machine and they let me bring my dog,” she recalls. “Somebody came and was filling out a lottery ticket next to me while I was reading, which was hilarious. I signed a bunch of books next to the hot-dog roller.”

Mostly Dead Things will take Arnett considerably farther afield, spreading her Florida realness via a coast-to-coast book tour. Rapturously reviewed a week early in the New York Times, her debut novel is as punchy and complex as she is. It’s a queer novel that consciously eschews coming-of-age trauma in favor of what Arnett calls the “lesbian domestic”: a family drama whose protagonist just happens to be a gay woman. It’s deeply rooted in a place, central Florida, that seems utterly singular yet archetypically American. It’s a romantic tragedy about a love triangle in which the female narrator gets involved with her brother’s wife. It’s a meditation on art and craft through sculpture and taxidermy and the differences and similarities therein, and it begins with a suicide, ends with an arson, and is never not sharply funny.

At the heart of the novel is Jessa-Lynn Morton, lifelong Floridian, third-generation taxidermist, and queer Everywoman trying to keep her family together in the wake of her father’s suicide. That means running the family business, taking care of her niece and nephew, and talking through the grief of others. Jessa-Lynn’s mother’s way of coping involves crafting sexually explicit dioramas out of her late husband’s taxidermy for a local art gallery. Jessa-Lynn hates the art, but falls into bed with the gallery’s owner, Lucinda.

Jesse-Lynn needs to feel in control, but can’t even make sense of her own multiple traumas — namely, finding her father’s dead body and, as importantly, losing her brother Milo’s wife, Brynn, the love of both their lives, who abandoned them (and her children) years earlier without a word of good-bye. There is also, of course, her sexuality, but Arnett’s tale bears none of the traditional marks of the “coming out” novel.

“I know that there’s space for coming-out stories,” Arnett says. “When I was writing this book, I knew I wanted it to be very queer, but also just to be about the everyday passage of time. What does a day look like in the life of a queer person? What’s the day-to-day domestic routine if you just happen to be a queer woman? A person who’s going about her life, fucking and fighting and having shit happen to her family and being passive-aggressive and having other outside traumas to deal with — who, you know, incidentally, is gay.” Jessa-Lynn’s family accepts her queerness implicitly, as does the novel; it’s just a fact of her existence. It’s not anywhere as prominent in the story as, say, taxidermy.

The practice of preserving and stuffing dead animals is, in a way, the most autobiographical aspect of the novel. (The Morton family is not modeled on Arnett’s, and she certainly isn’t Jessa-Lynn.) The author is no taxidermist, but she grew up around plenty of it. “At my house we had taxidermy. The church I grew up in had deer mounts,” she says, laughing. “You’ll be looking at someone’s Precious Moments figurine and then there’s also a stuffed squirrel there. I’d never really thought too much about it until I was thinking about how funny taxidermy could be. Before I started writing the book, I was spending a lot of time looking at a lot of fucked-up taxidermy.”

These dead things are no superficial quirk; they are central to the drama, the comedy and the tragedy. In one scene, Jessa-Lynn finds her mother crying on the floor of her shower as her taxidermied Pomeranian, Sir Charles, watches her from atop the toilet seat; in another, her nephew cooks up a scheme that involves kidnapping a flock of peacocks from a nearby golf course.

Half of the novel takes place in the past, conveyed in alternating chapters named after taxidermied animals (“Pavo Cristatus: Indian Peafowl,” “Canis Lupus Familiaris: Domestic Dog”). This gives Arnett all kinds of room to play. Brynn never shows up in the present, but in flashbacks she becomes one of the book’s best-rendered characters.

“I really wanted the present to run in this very linear fashion, very up-to-the-minute in linear time, and I wanted the past to function how memory functions for us,” Arnett says. “Memories are brought on by a scent, a smell, an image, a sound we hear. That’s how memories pop up and crop up on us. So I loved the idea of thinking about them in terms of the physical embodiments of these specific animals.” Time isn’t a flat circle, but a stuffed animal — a ravioli.

Mostly Dead Things is never any one thing: funny, awful, gritty, sweet, economical, messy, and shapely. Ultimately, it homes in on the near-universal struggle to become a better version of who we are for ourselves and for those we love — without losing our internal selfhood. In terms Arnett might use but never explain, it’s about being the best ravioli you can be.