The pantheon of acid casualties in rock is a hallowed and tragic honor. And last week, Roger Kynard Erickson at last ascended — joining the likes of Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett, the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones, Alexander “Skip” Spence, and Vince Taylor, to name but a few — dying at the age of 71. In a more just world, the passing of Roky Erickson would have garnered accolades worthy of one of rock music’s seminal figures, a man whose raw talent drew comparison to James Brown, Bob Dylan, and fellow Texan Buddy Holly. As frontman for the 13th Floor Elevators, Erickson birthed the very idea of psychedelia in the 1960s. If you’ve ever sought transcendence from a rock and roll record, or dove headfirst into drone or chopped and screwed for its psychotropic properties, or simply wanted release from this earthly realm via your speakers or headphones, Erickson was your patron saint.

Unlike those other casualties, though, Erickson survived against the odds and enjoyed numerous renaissances well into the 21st century, embodying garage rock, punk, new wave, and even indie over the course of his lifetime. Roky’s story is quintessentially American, not just in that “indomitable pioneering spirit” sort of way, but also as victim to the blights of our country, from our conflicting drug culture and draconian drug laws to our cruel penal system to a woeful lack of mental-health awareness. In that tragic sense, Roky embodies the American story.

The oldest of five boys, Roky Erickson grew up in a post-war household in Central Texas, with a hard-drinking, workaholic father and doting, eclectic mother. Reared on comic books and horror movies (which would manifest again in his bracing ’70s output) and early rock and roll, he dropped out of high school weeks before graduation and joined a local band, the Spades. Before the age of 19, Erickson had already penned a classic: From its opening E-D-A-G chords, “You’re Gonna Miss Me” is a ferocious, stomping early example of garage rock, an update of blues tropes delivered with an insouciant, teen snarl by Roky.

Within a year, he had joined another local band, the Elevators, and rerecorded the song, which was a regional smash and made the charts. Tommy Hall, UT-Austin psychology student and electric jug huffer/guru/ LSD pusher, recruited Roky and extolled the drug’s virtues on the band’s 1966 debut album, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators: “Recently, it has been possible for man to chemically alter his mental state and thus alter his point of view … therefore approaching them more sanely,” read the liner notes, ominously calling such ingestion of drugs “this quest for pure sanity.” Roky fully embraced that philosophy and became its mouthpiece. Soon, they were the most popular band in Texas, and when drug busts sent them out to California to escape the legal heat in their home state, it became the catalyst for what would soon be the Summer of Love. Back in early 1966, when the Warlocks had just changed their name to the Grateful Dead and were still doing R&B covers, before Janis Joplin was inspired by her fellow Texan and joined Big Brother, when the Beatles were winkingly making “toke” sounds on “Girl,” the Elevators were singing about mind expansion and dosing before they hit the stage. They’re believed to be the first band to use the term “psychedelic” to reflect their sound and, soon, Bay Area bands were following their lead.

With a voice somewhere between Buddy Holly’s winsome yip, Dylan’s folky quiver, and a Hill Country coyote howl, Roky was a rock star in the making. Longtime champion Bill Bentley, onetime senior vice president of publicity at Warner Bros. Records and the person responsible for an early ’90s tribute to Erickson, said Roky “was the most electric performer I’ve ever seen, and that includes Hendrix … He was possessed, so vivid and mesmerizing. His voice was so sharp and cutting — sometimes he’d get lost in his screams.” But within a year, Erickson’s high intake of LSD exacerbated latent schizophrenia. It got to where he was afraid to go out onstage for fear that the audience would see the third eye in the middle of his forehead. At other shows, he would be in a vegetative state. As Bentley put it: “I’ve never seen such brilliance accompanied by such a fall, where every wrong thing that could happen happened.”

Much like Jim Morrison at the time, Roky was deemed a demiurge and friends and hangers-on continued to feed him whatever drugs were on hand, further exacerbating his mental fragility. Friend Terry Moore told Texas Monthly, “Everybody treated him like a god. Nobody would say, ‘Roky, you need to straighten up.’” Facing a ludicrous ten-year charge for possession of a single joint in Texas in 1969, he pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity to avoid a prison term.

Originally housed in Austin State Hospital and waylaid by the antipsychotic drug Haldol, he kept breaking out and soon wound up instead in East Texas and Rusk State Hospital, a cruelly punitive move that put Erikson in the midst of violent murderers and the criminally insane. He was dosed with another antipsychotic, thorazine, and was subjected to three years of electroconvulsive shock treatment. Listen to the recordings his mother made during her visits in the early ’70s (collected on the 1999 set Never Say Goodbye) and you can hear the heartbreaking fragility of a man using his voice and guitar to try and keep the pieces of his life together. Such were his gifts that he could make you tear up at the recital of the pledge of allegiance. In 1972, a judge deemed Roky’s “sanity restored” and he was sent home.

Roky had always been able to fearlessly mine the darkest side of mind expansion (“You start to fight against the night / That screams inside your mind / When something black it answers back / And grabs you from behind,” he sings with a shiver on “Reverberation”) but being “cured” left Erickson more shattered than before. Paranoia and delusions consumed his new music. As R.E.M.’s Peter Buck recently told the Washington Post, Roky’s songs “are concise and terrifying in their power.”

“Creature With the Atom Brain,” “Red Temple Prayer (Two Headed Dog),” “I Walked With a Zombie,” “Bloody Hammer,” “Don’t Shake Me Lucifer”: The horrorcore of these late ’70s and early ’80s Roky songs reflect the beloved horror movies of his youth (some films conjured solely in their creator’s mind), the campiness of them warped into something nightmarish thanks to Roky’s feverish delivery. And then there’s the sweet sublimity of “Starry Eyes,” the kind of melody that Roky once quipped was “sent from heaven by Buddy Holly.” Generations of Texas musicians would queue up over the next few decades to resuscitate Roky: Doug Sahm, the Butthole Surfers’ King Coffey, Charlie Sexton, Okkervil River, Black Angels, and the like were there to help Roky make new music. But just as often, he was ripped off, signing away royalties and songwriting credits and leaving his legacy in tatters. It would take decades for him to start seeing payments for his decades of music.

And his mental health deteriorated further. Interviewed about his spiritual background in 1980, he calmly explained: “I’ve gone through three changes. I thought I was a Christian and then I was with the Devil, where I sold my soul to the devil. And then the third where I know who I am. I feel like I’m a monster. I know I’m the robe of many colors spoke of in the Bible: a demon, a gremlin, a goblin, a vampire, a ghost, and an alien with a brain about this big.” He hoarded mail and wound up charged with a federal offense for mail theft. Friends who used to visit him in the 1990s recount visiting his home and encountering a din of electronic noise: TVs, radios, and stereos blaring to drown out the voices in his head. By his 50s, he wound up living under the care of his mother again, who was negligent in his medications and well-being, preferring prayer rather than medicine to address her son’s dilapidated state. At one point, Roky’s teeth had deteriorated to the point of becoming abscessed, threatening to infect his brain.

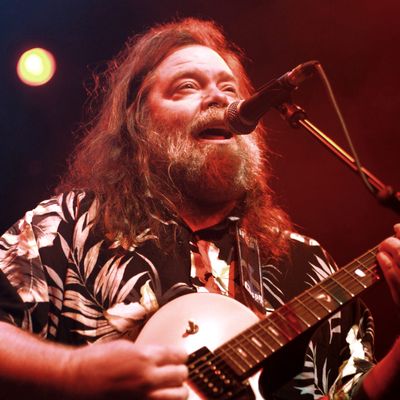

It was his youngest brother Sumner — himself a prodigy at the age of 18, playing tuba in the Andre Previn-led Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra — who finally wrangled legal guardianship of his oldest brother in the 21st century. Roky received dental care and drug treatment that brought a sense of stability back to the man. He even made a late-career highlight with Okkervil River, 2010’s True Love Cast Out All Evil. That I could see the man play live at the Music Hall of Williamsburg in Brooklyn in 2014 seemed like no small miracle, though at the same time, he seemed like a shadow of himself, not quite present save when it came time to open his mouth again and let out that hackle-raising, infernal howl for the encore of “You’re Gonna Miss Me.” It made clear the genius of Roky, wherein forces in eternal conflict co-exist. Presence and void, angel and demon, as Roky once sang: “The kingdom of heaven is within you,” implicit that hell was also there.