This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

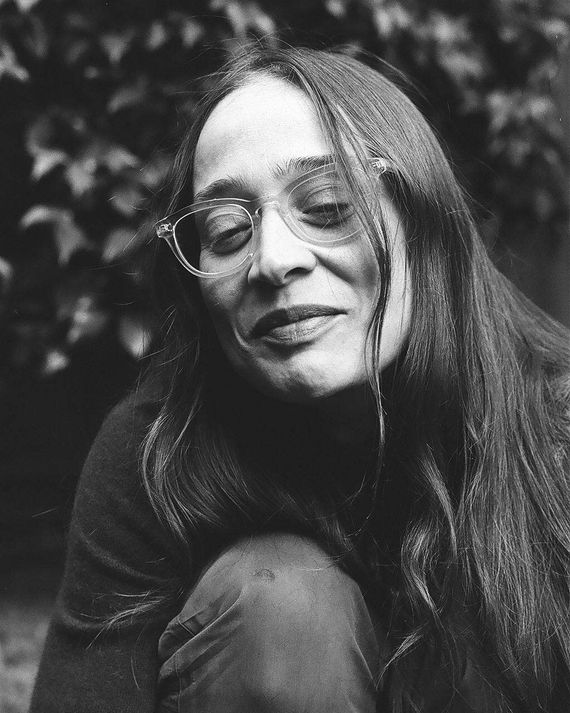

Fiona Apple rarely leaves her house, which is why she’s yet to see Hustlers, the movie that features a be-sequined Jennifer Lopez pole-dancing to Apple’s beloved 1996 anthem “Criminal.” “Listen, I just want to say: I would give my song to Jennifer Lopez to dance to for free, any day, any time,” laughs Apple. “I really want to see the movie. If I were a person who actually left my house, I’d go.” She’s been reclusive for a reason, though: She’s hard at work on a new album that was supposed to be done “a million years ago,” and is finally, hopefully, maybe going to be released into the world next year. “I mean, I don’t know!” she tells me over the phone from her home in Los Angeles. “I go off and I take too long making stuff. It’s hard to say.”

How I ended up on the phone with Fiona Apple, talking about J.Lo and Apple’s career and Neil Portnow and insomnia remedies, is nearly as difficult to explain. Shortly after Hustlers premiered, I received an email from someone claiming to be Fiona Apple, who’d found my information on my personal website and was emailing from a nondescript Hotmail address. Part of me was suspicious and part of me was eager to believe: Of course Fiona Apple wouldn’t employ a publicist; of course Fiona Apple would have a nondescript Hotmail address. Apple got straight to her point. “I saw that you were one of the only ones to notice what Variety’s Twitter did with that Lorene Scafaria interview,” she wrote, referring to a recent and bizarre incident involving the Hustlers director. During the interview, Scafaria applauded Apple’s decision to donate two years of royalties from “Criminal” to an organization that assists refugees. Except in the video initially tweeted by Variety, Scafaria’s use of the word refugees was dubbed over, rather nonsensically, to imply that Apple is donating royalties “to the movie.” After Scafaria called out the dubbing, Variety scrubbed the original video from the internet and reposted it with corrected audio, calling the misstep a “glitch.”

“They overdubbed the word ‘REFUGEES,’” Apple continued. “No one seems to think this is a big deal, but I think it is, and I’m wondering if you’ll write something about it. Email me if you want to talk.”

A few days later, I hopped on the phone with her, assuming we’d discuss the incident and go our separate ways. Instead, she happily remained on the line for 45 minutes, discussing, well, whatever she wanted to discuss. Apple has always done things on her own terms; so much of her mythos is tied to her refusal to play by the rules. She releases music on her own schedule — only four albums, roughly one every six to seven years, since 1996. She hasn’t done a conventional interview in years; when she was profiled back in 2012, by this very magazine, she smoked hash out of a Champagne flute while musing about human compassion. The Apple I spoke to sounded happy and more grounded than most nonfamous people I know. She signed her email with a balloon emoji. Before our phone conversation ended, she trilled lightly, “Keep in touch!” And she meant it. A few days later, she texted to say she “forgot to tell her J.Lo story,” then proceeded to divulge incredible details about Lopez’s “beautiful ass.” Below is our sprawling conversation (lightly edited for clarity), text addenda and all.

From your perspective, what is happening with the Variety video?

I can’t be sure, really. Scott Hechinger from Brooklyn Defender Services sent me that video. And I was like, “What the hell is that? It looks overdubbed. Why is she saying, ‘[She’s also now giving all of the money she makes from “Criminal”] to the movie?’ ” I sent it to my manager and my lawyer, and they were like, “Yeah, it looks like it’s really overdubbed.” They got in touch with Variety, and Variety took it down. [They] called it a technical glitch. But you saw it. That didn’t look like a technical glitch.

What do you think the motive would be for overdubbing the word refugees?

I can only guess they don’t want to alienate any viewers, any ticket buyers, who may be more on the other side of things [politically]. The only reason I can think of is money. But I don’t know.

“They” meaning the studio? [Editor’s note: When reached for comment, STX Films, the studio behind Hustlers, declined to comment. In a statement to Vulture, Variety maintained that the incident was a “technical audio issue” and said it was “absurd” to suggest otherwise.]

I get that that’s how studios think, but they could have just taken out the whole sentence. They didn’t have to say I was giving the money to the movie. Who the fuck gives their royalties back to the movie?

I know you don’t do a lot of press. What inspired you to reach out to me about this?

I think this is the first time I’ve ever asked somebody to do an interview. [Laughs.] As my friend Zelda would say, I’m a justice kid. It doesn’t sit right with me that they covered over the word refugees. I don’t want to throw a wet blanket on the movie or anything; Lorene Scafaria is bringing awareness to what sex work is like, and Jennifer Lopez is moving things forward for Latinas and women everywhere. Everyone has something that they care about, and I care about this.

When and why did you decide to donate the proceeds from “Criminal” to the organization While They Wait (which provides legal and other services to immigrants in the U.S.)?

I was, like everybody, getting really frustrated. A lot of us want to go down and get these kids out of their cages and give them food and blankets and showers, but there’s no way to fucking get in there. They won’t let you in and they won’t even take donations. I was looking on Twitter, which is unusual for me. I did a Twitter search on immigration and I found [Scott], and this organization made the most sense for me. If I can’t get stuff in there, at least I can try and help them get out of there. When you can help and you want to, it’s really wonderful to do that.

Did you know, at that point, that “Criminal” was going to be in Hustlers?

To be honest, I really don’t think I remembered that I had given the song to Hustlers. And I was like, “Whoa, I forgot about that! That’s so great.” Basically, every single time any college dancer or So You Think You Can Dance [contestant] asks, I’ll give them the rights. “Criminal” has always been what people ask for the most, so it’s always been my little help-out-people song.

What made you decide to license “Criminal” to Hustlers? I know you’ve never given the song to a movie before.

It was just about what it was and who was in it. But I didn’t know [Jennifer Lopez] was going to be dancing to it. I’ve seen a lot of pieces about how they got [the rights to] “Criminal,” but it’s just funny to me — there’s a disconnect between agents, because I never got a video of the dance. And I want it, bad! I’m all for the movie, though, and I’m excited to see it.

Lorene says she wrote you a letter, too. Did you ever receive it?

I don’t remember receiving a letter from her. But that’s what I’m saying — there’s some kind of disconnect. I believe her that she wrote me a letter, and that she sent me the scene. But who knows what happened? Maybe somebody in the studio is like, “We don’t trust that girl with this! Don’t send it to her.”

You’re very discerning about where your songs go. I remember reading that you didn’t let Panic! at the Disco use a sample from The Idler Wheel.

You know, can I just say something about that, which is funny? I don’t remember hearing the song they wanted to put that in. The reason I didn’t give it to them — besides the fact that I don’t remember it, so it probably wasn’t that great to me — is because this other guy had just used a sample of that same song and had signed to my label. He’d already made a big video with that song in the background. So I was like, “Hey, what the fuck is going on here?” I ended up giving permission because I didn’t have a choice; they’d already used it in a song and video. And then Panic! at the Disco asked, and I was like, Wow, I can’t believe they even asked me. Usually people just go ahead and use it. [Update: After this interview went up, Apple posted a video on Instagram calling out Lil Nas X for doing just that.] I was just trying to not shit all over somebody else’s sampling of my song by doing it twice, but [Brendon Urie] called me a bitch. Which I think is hilarious.

Did that get to you?

Somebody calling me a bitch? No! It would get to me if I felt like I really was being a bitch, but I don’t know if he really meant it anyway. I just didn’t say yes. I mean, just use a different song. It’s not a big deal. I don’t know anything about him except for this clip. But it did look like he was entertaining himself in this clip, saying it. Like, “Yeah, I just said that!”

That would have made me feel terrible when I was 18, like, oh, one of my peers called me a bitch, and now everybody’s gonna think I’m a bitch, ahhh. Sticks and stones didn’t break my bones, but they fucking bruised me. It’s just words, but words hurt a lot. But now it’s like rhinoceros skin. It’s like somebody shooting arrows at you and they bounce off you. Now it’s like, it doesn’t even track.

How do you keep up with what people are saying about you? Are you lurking online?

Other people tell me. I’m not online. I don’t have Twitter. I do search things, like when I searched the Hustlers thing … to see what people are talking about. That’s how I found you.

You famously wrote “Criminal” in 45 minutes at age 17, after the record label asked for a single. What does the song mean to you as an adult?

Right now the song itself, the lyrics, those don’t really mean anything to me. The way it started, the video, all the crap I got — using this song now, and using it in this movie for a purpose I believe in, is like reclaiming it. I’m not that scared girl in underwear anymore. The song isn’t that to me anymore. It’s my way of paying for things that I want to get done.

I do remember when the video came out, it was such a flash point for this very specific, male-dominated, shitty discourse — people fixated on your body and perceived sexuality, using phrases like “heroin chic” and dubbing your performance “pornographic.” What do you think about when you watch the video now?

I haven’t watched the video in a while. I’m still in touch with Mark Romanek [the director], and he’s a great guy and he’s my friend. That was just a situation where everything was set up when I got there. I didn’t have the treatment of how the video was supposed to be. They were expecting somebody to come up and be like, “Yeah! I’m sexy! I’m stripping!” versus somebody being like, “I’m sad.”

That’s really interesting in the context of Hustlers, too, because the film is about how women are valued and exploited under capitalism. When I spoke to Lorene and the cast, there was a lot of talk about how the majority of women have “danced for money,” whether literally or figuratively. Did you ever feel like you had to do that?

With that video, when they wanted me to do that, they didn’t get the results they wanted. Nobody has really asked me to shake my booty since then. At all. So I think I’ve avoided that. I mean, just the fact that I don’t actually talk to a lot of people means that I avoid getting a lot of annoying [requests]. It’s hard for me to answer stuff about my career experiences because for me, right now, it’s been almost a decade since I’ve been in that career. I forget that that’s my life sometimes.

What does your life look like right now?

Well, it is music now, because I’m finishing a record. But that’s all, like, me in my house, and I’m in control of everything. So I don’t have to be getting other people’s ideas of what I should be doing yet.

You’ve always been good at that — controlling your own narrative. How did you develop that power?

I don’t even think it’s a power. I do think I’ve always had it. It’s honestly a direct result of me never getting people’s phone numbers and never getting chummy with a lot of people. So then people don’t think of me to call up and badger to come out and do stuff. So I never go out and do stuff, because it’s never expected. My family hasn’t seen me at Christmas celebrations for years and years. So I just don’t get invited anymore. [Laughs.] I mean, that’s an exaggeration.

I assumed in the beginning I could do whatever I want. If you’re just doing that from the beginning, and don’t have any doubt about it, then that’s how it goes. I had no idea I was setting my own narrative by not acting a certain way or taking anybody’s advice.

That’s what drew so many women I know to you in the first place. We still talk about your 1997 VMA acceptance speech, where you said, “This world is bullshit.”

This Variety thing totally made me think, This world is bullshit. And not talking about this entire world, but just the showbiz world.

What adjective would you use to describe the world now?

The world is many, many, many, many things. I never said the world was bullshit, I just said this world was bullshit. Referring to the room that I was in and the whole music scene, which — it’s not bullshit anymore. It’s the bull who ate that shit and then shit it out again, and then ate that shit and then shit it out again, and then ate that shit and then shit it out again, and then ate that shit and then shit it out again, and now it’s that bullshit. [Laughs loudly.]

That was … incredible. What makes that the case?

I have no idea. I just think everybody wants to be a star and everybody is willing to do whatever the fuck it takes to be famous. That means pushing people out of the way and not caring for other causes and only caring for yourself and what your fucking brand is, whatever the fuck that means. I think people are getting more and more selfish. Not all around — it’s hard to answer big world questions. I don’t know why things are the way they are.

How do you make new music within that sort of system?

I worry a lot about what it’s gonna be like when I actually have to put out an album and go out there. I think I’m getting close to finishing. While I’m doing it, I have to put the rest of it out of my mind. It’s just fun. It’s just me making stuff, on my own time, and then not making stuff for years, and then starting to make stuff. It’s just around this time when things are starting to shape up with the album and everything is getting toward the finish line — that’s when I start to get a little concerned for myself. I’ll be okay, I just know that it’s not going to be all enjoyable. Every time I go out on a photo shoot, I think, This is different from seven years ago. I don’t feel like this anymore.

Are you able to detach yourself from the publicity process more than you used to?

Not exactly. I might be able to, but it’s more that I’m like a scientist and curious about how I’m affected by these things at this point in my life. After seven years away, what is she like in this situation now? I’m sort of observing myself, seeing what it’s like.

When do you think the album might be ready?

I mean, I don’t know! It’s hard to say. I was supposed to be done a million years ago. And I go off and I take too long making stuff. I’m hoping for early 2020. I think.

Can you compare it to any of your earlier albums? Or does it feel like it’s completely its own thing?

It’s probably its own thing. But I don’t know how to articulate that. It’s like, if you’ve been working out every day for a month and then nobody sees you, they see the difference, but if you’ve been doing it all the time, you don’t really see the difference. I can’t really know the growth or the evolution or anything like that in what I do, because I’m in the middle of it.

You take your time between albums. When do you know, okay, it’s time to start making music again?

A lot of times it’s actually because I get kicked in the ass by the musicians I work with. They’re like, “Come on, when are we gonna get back to the album?” I’ve been making this album with my band, and they all have other gigs. They’ve got to make money. When it’s just me recording myself, it’s different, but with the band stuff, you have to wait for everybody to be in town and be able to do it. So that slows things down a bit. And I tend to forget about working after a while. And then be like, “Hey, what’s going on? Let’s play, let’s play.”

What have you been doing over the past few years when you haven’t been making music?

Hmm, what do I do? I mean, I’m always writing in my head. I spend a lot of time with my dog. I live here in my house with my friend Zelda and her dog, and we just hang out. We play with dogs and work on our stuff and go out for walks. I have a very simple life.

In that life, does it make its way to you that you’re something of an icon for your refusal to conform to certain ideas about womanhood? Are you aware of it, and does that get internalized for you?

Hearing you say that … I like the sound of that. I will choose to believe that. I’d like to internalize that. That would be great.

When you do leave your house, what’s your relationship like with fame, with your fans? Do you interact with them, do they approach you?

I don’t get approached a lot. I’m not around people enough for it to be a thing. I haven’t noticed anybody notice me in [a long time] … but when I’m out with people, sometimes they’ll notice me getting noticed. Anytime anyone talks to me, they’re always really nice. Way back at the beginning, I was thinking I could put out a CD and I’d make all of these friends, and I wouldn’t know them but they’d know me, so that when I met them I could just say hello and we’d already be friends — I think it actually came true in a way. Not that I’m actually friends with everyone I meet. But if you’re intimate with my music, you’re intimate with me and I’m intimate with you. I feel like you’re my friend. Maybe that’s a little bit too childlike, but I do feel like that.

Vulture profiled you in 2012 and you had a great quote, which I’ll read to you. The profiler starts: “I assumed she wanted to talk about her album; she said she didn’t care. I told her I thought it was her best work; she said it was funny because she’d run into her ex-boyfriend, the filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson, and ‘he remembers me as somebody’s who’s been down on themselves from years ago,’ and when he’d asked about the album, she told him she felt ‘really, really happy, I felt like I can die now, I’ve done what I want, this is me.’” Does that resonate for you now?

Yeah. I felt that way after that album, and this is me getting to that place with this one. The last album, it was just me and [producer] Charley Drayton, doing it all ourselves. This time, it’s just me and the band. The more control you have over something, the more it’s your baby, the more you care about it, the more it feels like an accomplishment. The last record and this record feel more like mine than the other records. You know? Not that I don’t feel like the other records are mine.

What’s your relationship to your old music? Do you ever listen to it?

No, no, no. Why would I? Well, I do freak out before I go on the road because I don’t know how to play my songs anymore and I have to relearn all of them. I have some homework.

Vulture recently did a long Q&A with Liz Phair, and she said something really interesting: “When I’m not working, I safeguard my time to go into a dream state and not have to think about the commercialization of my art or the commodification of myself. I take ‘Liz Phair,’ I put her on a hanger, kind of like Mr. Rogers, and I put her away in a closet. I’m not ‘Liz Phair’ anymore.” Do you feel that way?

Yeah! I don’t feel like I have a Fiona Apple to take off and put in a closet, like a big persona like that, like I have to click my heels. I don’t have such a public self, so I don’t think I really have to put it away. But I do feel like when I’m not in public, it is like taking off a big heavy coat. And then just being naked by yourself.

Do you think you’d want to spend this much time by yourself if you weren’t famous?

There’s no way to really tell, but I think so. I mean, when we were trying to come up with my stage name, my mom wanted it to be “Fiona Lone.” “Because you’re always alone!” That was when I was 17, so I’ve been this way for a while. Although I’m actually not alone that much now, because my best friend Zelda lives with me, so we’re around each other all the time. I just don’t have a social need to go out.

You’ve sung and talked a lot about your inability to sleep, but you mentioned your lucid dreams in a recent Q&A. As a fellow insomniac, I need to know: How’d you solve the sleep issue?

I’ve been through a lot of medication, and for a long time, I think, the medication was helping me sleep and also helping me not have nightmares, but also giving me nightmares. I was on way too much medication for a while. Now I’m on way less medication. But pot helps me. Alcohol helped me for a while, but I don’t drink anymore. Now it’s just pot, pot, pot. And I get up at like 5 a.m. [Laughs.]

I watched the fan Q&A you did on YouTube last year, which was really fun and rare for you. What made you decide to do that? I don’t think you’ve done that before.

No. Well, I met a fan of mine in the alley of the Largo [in Los Angeles] about five years ago. Her name was Ashley. She wanted to sing part of my song with me, and we sang it, and she was very sweet. We sat down and she told me about Simon, who runs a Tumblr on me [Fiona Apple Rocks]. I’ve stayed in touch with her and I call her my pseudo-daughter. And I stay in touch with Simon now, too. Simon’s my friend now. We talk to each other about nothing to do with his postings. And he said there were a lot of fan questions, and would I do something like that?

Can you tell me the story of giving away your Grammy? You told TMZ in 2017, “I don’t know where it is at this point. I gave it away.” Why, and where is it?

I gave it to this school, and I have to get it sent back. For the longest time it was at somebody’s house and they wouldn’t give it back to me, and I said I was going to give it to my grandmother, but I was really going to donate it to a school so they could auction it off. But it turns out you can’t auction it off. So now it’s in this office in this school, and I haven’t gotten around to writing them to get it back.

What do you think about Neil Portnow stepping down as president of the Recording Academy, after he said that women needed to “step up” as musicians? I loved your Kneel Portnow shirt.

Personally, I met him a couple times, maybe. I know some people who think he’s a really great guy and didn’t deserve all that flack that people like me gave him. But, I mean — if you say something like that in the first place, your head’s in the wrong place. That’s not misspeaking, you know? [Laughs.] I don’t have any evil thoughts about the guy, and I made that T-shirt because his name lends itself to that and it was too good not to do. And because I felt that. But you can’t just say something like that and be like, “I love women! I’m doing something for women!” There’s clearly something going on, there’s a problem, when you’re like, “Well, women just need to be better.”

Your work, for a long time, was discussed in tandem with your image, especially by male critics in the ’90s, who wrote some pretty unfair shit about you. Do you think things have gotten better for women in the industry in that sense?

I’ll have to get back to you once I get into things and see how I’m treated. I think it’s a lot harder to treat women the way they were treated in the ’90s now because you can get called out so easily on social media. If somebody does something shitty nowadays, a 17-year-old singer can get on their social media and say, “Look what this fucker did! It’s fucked up.” Like when Taylor Swift said, “You took my music and I didn’t get a chance to buy it,” and was able to explain what happened, rather than being some 17-year-old girl who couldn’t say anything. So people don’t want to step up and be seen as the bad guy in public. But I don’t know. I’m really speaking out of my ass because I haven’t been in those situations for a while. But we’ll see.

Were there moments in your career when you felt like you were without a voice?

I felt like I couldn’t speak out until I did that [VMAs] speech. And then I felt like, Now I got that out of my system, and I’m able to speak out. But it’s very difficult when you’re young and looking for approval, and you want to be understood, and you’re in a vulnerable position and you want to be pleasing to people who are helping you. Everybody’s got really strong opinions around you, from the makeup artists to the producers, everybody’s been in the business for so much longer than you, and they can drown your opinion out and you don’t even know what you think anymore because you haven’t had time to figure it out. You didn’t have time to figure out, what would I want to wear? Because they already laid it out for you. And you don’t want to be ungrateful, because they’re giving you your life, right? It’s gotta be tough for really young people.

NPR recently called you the “godmother of 2019” —

What?!

Meaning you’ve influenced Billie Eilish, Lana Del Rey, Maggie Rogers, etc. Do you think that’s a fair assessment? Do you listen to any of them?

I don’t really follow, uh, I don’t. I feel bad. But I don’t.

You got really candid with TMZ last year when they caught you at the airport. They asked you if you felt that the abuse of power by men and sexually predatory behavior toward young women was just as prevalent in the music industry as it is in Hollywood. You replied: “Fuck yes. Are you fucking kidding me? Yeah.” Is there any particular thing or person you were referring to?

I have a million stories I could tell. But I can’t tell them. Legally, I cannot. I’d be putting myself in danger if I told some of them. I think when I’m older I’ll write a book. And then I can say whatever I want to say. [Laughs.] I’ll write my story.

Text from Apple a few days later:

So I was thinking about three things I call bullshit on (music business, Trump, Variety’s Twitter “glitch”). It’s all about money. That’s why each one of those things gets to me. It’s selling lies, for personal gain. BUT — more importantly, I forgot to tell you my J.Lo story from like 1996 or ‘97! I was in NY at a pre-Grammy party (because I used to go to shit like that). And my sister Maude was with me, but she was on the other side of this big room filled with little tables and mingling celebrities and executives… So J.Lo’s album hadn’t come out yet,and nobody had started talking about her ass yet — and I swear I saw her (J.Lo), and ran to get my sister JUST to show her how beautiful that ass was — and the moment I pointed her out to my sister, J.Lo turned to speak to someone and her butt was just above table-level, and her butt knocked over someone’s glass of champagne and she didn’t even notice. It was glorious.

Have you met her since?

No! And one of the few movie premieres I’ve been to was Out of Sight, but I didn’t meet her there either. (I used to love how she says in that movie, “You wanted to tussle. We tussled.”) And I was at the Oscars when she wore the Google-image-inspiring dress. [Editor’s Note: Lopez wore the dress at the 2000 Grammys.] Didn’t meet her then … We’ve been in the same room a few times I guess, but never met.

Well, she’s been saying complimentary things about you and your music on the Hustlers press tour.

She HAS?! I’m still getting over watching Lorene Scafaria say my name and seeing J.Lo nod, like she knows who I am — that’s just strange!

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.