When asked, the way one sometimes is, I’ll admit that I’m a kind of a Ringo. It isn’t an entirely accurate comparison, but it’s as close as I can get within the rubric of the Beatles. I’m probably a Charlotte too, but that’s not quite right either. I’m less judgy than she is, for sure, and I’m more squeamish than prudish. I’m a Capricorn, technically, but the thicket of flourishing astrology memes leaves me feeling confused rather than seen. When I was younger, I thought of myself as kind of a Woody Allen type, but you can’t really say that anymore. (Or rather, you can, but it means something different now.) I’m also easily pegged as a Hufflepuff, but I’m also also an adult, so that’s not always a dignified point of reference.

This year I learned that what I really am is a Speckle.

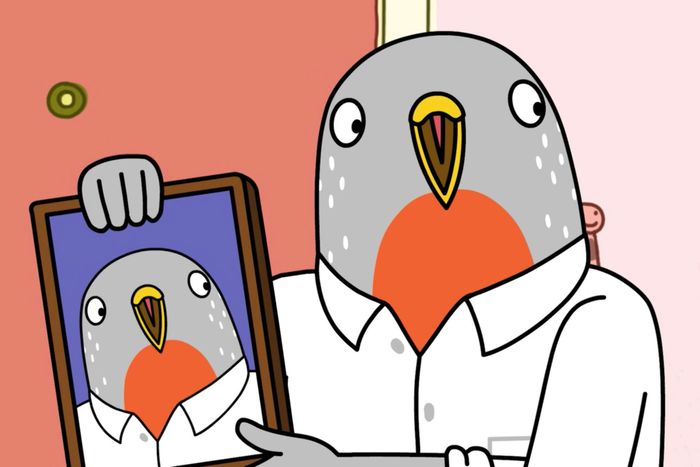

If you don’t know the reference, “Speckle” is a character from the animated series Tuca & Bertie (canceled too soon by Netflix, but hopefully still to live on elsewhere). If you haven’t seen the show — which is great and only ten episodes long — it follows the lives of best friends Tuca, an anthropomorphic toucan voiced by Tiffany Haddish, and Bertie, an anthropomorphic songbird voiced by Ali Wong. The show tenderly and hilariously explores issues centered on women’s friendships, female ambition, sexual harassment, and mental illness.

And then there’s Speckle. Speckle is Bertie’s boyfriend. He’s a robin, also anthropomorphic. He’s an architect. But, most prominently, Speckle is very nice.

As a person who is also often described, above all other traits, as “nice,” I feel a deep kinship with this sweet birdman. Lots of TV characters are presented as “nice,” but many of them are also annoying and selfish and rarely learn from their behavior. Ross Geller from Friends. Ted Mosby from How I Met Your Mother. Zachary Scrubbs from Scrubs (I think that was his name). They’re all kind of blandly nice without having any specific nice quality that I relate to or try to embody. And, more importantly, they aren’t messed up in ways that feel familiar, either.

Voiced by an exceptionally earnest-sounding Steven Yeun, Speckle models niceness in ways that I recognize and aspire to, but also in ways that frustrate me about myself. He is excited by the domestic elements of his monogamous romantic relationship. He legitimately enjoys and takes an interest in his partner’s important but complicated friendships. He has tried sexual things outside of his comfort zone for the sake of his partner (now-ex, in my situation) and then attempted to stay calm when she starts crying even though it was her idea. Is that too much information? I won’t go any further except to say: When Speckle showed Bertie the porn he watches, and it prominently features performers cooing gentle affirmations to one another (“I love you. I’m so glad we moved in together,” and, “I love that you can be honest with me”), I knew it was a joke, but I still thought, It would be nice if that kind of porn existed.

But just as importantly, Speckle had a set of nice-person flaws that you don’t often see depicted onscreen. The problems attributed to “nice guys” tend to be things like neuroses or shyness, which have not been my problems and aren’t Speckle’s. Speckle has almost too easy a time getting by. He thrives at work, getting out of his job as much, if not more, than he puts into it. Simply for having the idea to reinforce a window with the kind of wooden frame a child would draw, he is dubbed the Bad Boy of Architecture. (“I get to be called that because I’m such a good boy,” he tells Bertie later.) He receives an award for drawing a plume of smoke escaping a chimney.

Bertie is also advancing professionally, but through an arduous gauntlet of sexism, and while Speckle collects accolade after accolade, blissfully unconcerned that he didn’t have his phone with him, Bertie is in the throes of a panic attack in a supermarket, her boyfriend unreachable. Speckle’s ease of professional navigation stops him from empathizing with Bertie when her path to advancement is thornier, and her fulfillment is scarcer. When I saw that I cringed, as moments of my own blithe dude privilege hit me right in the beak, a series of brief instances of me assuring girlfriends past (and wife present/future) that things would be okay because … I don’t know … things seem okay to me.

Speckle’s problem isn’t getting in his own head, it’s his difficulty getting into someone else’s. Bertie has so much she’s up against, between the sexism she faces at work, her mental illness, and her desire for creative fulfillment through baking. When things get bad, she withdraws, fearful of sharing her anxieties with her partner. And Speckle isn’t always the best at drawing things out of Bertie. He blithely tries to plan for the future with her, but has trouble understanding why she isn’t fully onboard with his vision. Speckle tries to respect and support Bertie’s ambition and autonomy while struggling to assert his own needs, including his need to know what his partner is going through.

It’s rare to see a (bird)man on TV navigate the delicate straits between saying “you’ll be fine” and contorting himself into an emotional support structure, twisting and cramping in an effort to accommodate a partner’s opaque needs. It’s a very modern problem. How do you show support to an independent (bird)woman while respecting her space and making sure you aren’t just pushing your own feelings aside, mortgaging present happiness for a blissful future that may never come? How do you ask for concessions from someone the world already drains of so much?

In the season (and hopefully not series) finale, when Speckle tells Bertie that he can’t chase her anymore and she needs to let him in on what’s upsetting her, I felt weirdly proud of the way he outlined boundaries and foregrounded his own needs. And I felt a pang of memory, thinking back to relationships I’ve been in where I couldn’t do the same, situations where I kept accommodating a partner, prioritizing their happiness ahead of mine, and feeling like an idiot when we eventually broke up.

But as proud as I was to see Speckle put Speckle first, I was vastly more relieved when he and Bertie got back together. It validated my need to believe that you can be gentle but also firm, that you can grow and evolve into both a sensitive partner and an advocate for yourself. You don’t — as I used to fear — have to be an asshole to create space for yourself in a relationship.

So here’s to Speckle, for proving that sometimes the best way to be a bad boy is to be a good boy.

Josh Gondelman’s new book, Nice Try: Stories of Best Intentions and Mixed Results, will be available on September 17.