Despite the fact that they regularly fling their bodies off buildings, crash motorcycles, leap out of planes, and willingly set themselves aflame, stunt performers do not describe themselves as daredevils. They prefer their actual titles: martial artists, gymnasts, precision drivers, action actors. “People tell me all the time, ‘Oh, you must be so brave and fearless,’” says stuntwoman Mahsa Ahmadi. “No! It’s not about being brave enough to put yourself on fire, it’s about learning and practicing until you can do it safely, be in control.”

“It’s about hitting marks,” reiterates David Barrett, another humble stuntman (turned director). “You have to move like the actor you’re doubling, and the better chameleon you are — the better actor you are — the more effective you are to tell that story.”

Ahmadi will surely forgive us for stating the truth: Stunt work began with fearless daredevils. In the early days of film, if a director needed someone to jump off a cliff or fall out a window, they’d simply find someone brave or desperate enough to do it. Guinness World Records says the first person hired specifically to do a stunt was Frank Hanaway, whose claim to fame in 1903’s The Great Train Robbery was his ability to fall off a horse at speed. Stunt work was a big part of early silent comedy too, with actors like Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin using physical gags instead of audible punchlines to land a joke. By the mid-1920s, movie houses began seriously worrying about the well-being of their stars, and so it became more common to substitute a stuntman for the lead actor in risky shots. As silent films gave way to swashbuckling adventures and Western action flicks, a community grew around the performers who could fight and fall, swing through riggings, and ride a horse while shooting a gun.

Modern stunt work started in the 1960s, when many of the cowboy stuntmen turned to horsepower of a different sort, prompting the car-chase movie to replace the Western. In the 1970s, stunts from other countries began to find an audience in America too, as Hollywood integrated martial arts into its fight scenes and added Japanese-inspired drifting to its car chases. Developments in special effects came later, changing the landscape for stunt performers, but in no way replacing them. “You don’t need hundreds of stuntpeople working on the set with you anymore,” says stunt coordinator Jack Gill. “When I got in the business, you’d need 100 stuntpeople for a big Western or war scene. Nowadays with CGI, you can create that. You can bring in 30 to 40 people and create the others.”

“But it’s offset,” he adds, “because instead of there being maybe 30 or 40 projects to work on, there are thousands, and there are jobs all over the world.”

Speaking of drifting, the biggest difference stunt performers identify in their industry today is a trend toward hyper-specialization. “Everybody’s gotten so much better at specific things,” said David Barrett. “Everybody has a real specialty. Now there are world-class athletes in each category.”

“It’s still a bit unusual to be ‘just’ a car person,” said stunt driver Sera Trimble. “But I don’t do falls. I don’t do fire. I drive cars and put them where they need to be.”

Here, eight stunt specialists explain some of the hardest days of their career so far:

Transformers (2007), the old Camaro scene

James Smith, stunt driver: One of my most challenging [stunts] was skiing the Bumblebee on two wheels through the tunnel on Second Street in Los Angeles for Transformers. The asphalt in tunnels isn’t as smooth as on a regular street because the paving companies can’t get all their equipment in there. So it’s always rougher in a tunnel.

The scene was to have the old Camaro on two wheels. In an older car, the suspension can be a little wonky, and I’ve got to get that car tipped up to the point that it’ll drive while my other door’s almost rubbing the ground. But then the ground is all uneven, and I’m trying to navigate that car with the mirror all but rubbing the pavement. Trying not to wreck it but also trying to steer it.

To get the car up on two wheels, you drive it off a ramp, and when you hit the ramp and the car comes up, it’s not all the way on its balance point. When you come off the ramp it’s still in a turn. So until I get it to the balance point, I’m still turning. When you’re up at the skiing point where the car isn’t balancing, your eyes look out and see the horizon all sideways and your mind has to say, Yep, that’s normal. So there I was, in the tunnel, looking at a concrete wall sideways right in front of me, trying to decide if I should keep going and try to turn it the other way or crash into the wall and make everybody mad at me. I think it took four tries to get it, an hour or two. These days I could whip it out in 20 minutes, but 13, 15 years ago, I wasn’t that experienced. I was embarrassed that it took me that long, wasting Michael Bay’s time. I was so stressed.

Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings (2021), the Full Twist Sidekick

Brian Le, Martial Club:

I played a Death Dealer in Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, and there’s this one move I pulled called the Full Twist Sidekick. It’s never been done on film before, and that’s our mentality when we approach action: if we get the chance to choreograph anything, we always try to think of something that’s never been done before. If we’re paying homage to something that has been done before, you have to elevate it — put your own flare on it and make it a little different. But the Full Twist Sidekick hadn’t been done on film before.

There was this one moment where they allowed me to pull any flying kick I wanted. During rehearsals, I really fought for the kick. It’s not easy to do — obviously you’re spinning, twisting 360 in the air, and then you have to land a kick onto someone, and be accurate with it too, all in one shot. You never want to cut it up. You want to be able to pull the camera back and show the performers actually doing what they’re doing.

I was able to nail it every time in rehearsals, but when you’re actually shooting in a mask, you can barely see. You’ve got the strobe lights from the high rise, so everything is more dim. Your aerodynamics are off because your costume’s a little tighter to move in. So I wasn’t nailing it the first few takes. We just kept pushing for more and more and more until we finally nailed it. That is the concept of the thousand takes shot. If this shot matters that much to you, how much are you willing to push forward to make that shot happen, and to capture that on film? Because on film, it lives forever.

Suicide Squad (2017), doubling Margot Robbie

Melissa Stubbs, stunt coordinator: Something that sticks in my mind is Suicide Squad, doubling Margot Robbie. The scene is, they wanted her to crash a motorcycle to get the Joker’s attention because she’s in love with him, and he’s in a Lamborghini. I said there’s nothing sexy or graceful about crashing a motorcycle. It’s just a hot mess. I said, “How about she lays it down kind of coollike and then gracefully steps on top of it, and surfs the bike to a stop while it’s on the ground?” They were, “Oh, that’s awesome, can you do that?” And I’m like “Well, I’ve never done it but I think I can do it. I feel like I can.”

It took a bunch of rehearsals and figuring things out, and a bunch of failures, high-sided bikes and wrecking a bunch of Harley Davidsons, but I worked it out and it was like, Okay, that’s awesome, yeah. It was tricky. It took a lot of different motorcycle skills, and experience, and not folding under pressure, and just knowing and believing you can do something in order to get it, and we eventually got it.

The Exterminator (1980), a “big fireball explosion” followed by a 65-foot leap off a cliff

Jack Gill; action designer, 2nd unit director, stunt coordinator, and stuntman: When I was just starting out as a stuntperson, I had this one stunt that came up that five other or six other stuntpeople had turned down. What the director wanted was their lead actor running on the top of a cliff, and an airplane comes in behind him at night and drops a napalm run — which is a fireball bomb — that hits behind him. The director said, “I want the stunt double to get propelled off the end of this 65-foot cliff and land on the ground.”

Everybody had turned it down, and when they contacted me, I said, “Look, let’s try and figure it out.” At the time, I wasn’t really thinking of doing it. I was just wanting to know if I could really figure it out. I thought, I could do this on flat ground, so maybe. That’s kind of how it started. But once I got to the site and looked at it, it was a real 65 feet down to any flat ground and it was 22 feet out just to get to the first place where you could put an airbag. Nobody I knew of had ever jumped that far off a cliff to land on an airbag that was 22 feet out.

We brought in this thing called an air ram. An air ram is like a gymnastic beat board, but instead of having springs, it has these cylinders that are propelled by air. The air springs you up in the air and throws you out and away from the cliff. This was kind of a new device at the time we were doing this, but I had been using the thing for about eight months and was pretty good on it. I said, “If I could put an air ram on the end of the cliff, when you guys key the big fireball explosion, this should blow me off the top of the cliff and get me far enough out to land on the airbag.” In my mind, it was still pretty dangerous. You can’t miss the airbag because you’re going to die. Even if you land on a piece of the airbag, it’s still going kill you from 65 feet. We practiced on the ground and I did it five, six times and was able to get to 22 feet. So I said, “Okay, let’s line it all up.”

Once we lined it all up, the director said, “Well, along with the 13 gallons of gasoline that are going off behind you, I want to put another eight-gallon pod in the side of the cliff that blows out toward the camera. Are you okay with that?” And I said, “Well, as long as you can keep it away from me and I don’t go through it, that’s fine.”

So we get on the top of the cliff, and it’s nighttime, and we start to set this all up. I said, “Okay, let’s try and do this on flat ground again, just to make sure that I’m all tuned up and I’m all ready to do this.” I do it once and then I do it twice on flat ground, and it all works. But the third time the air ram misfires. It doesn’t go off. I turned to the special-effects guy and I said, “If my air ram doesn’t fire, are you still keying the explosions?” He said, “Yeah, the explosions are keyed off when your foot touches that air ram.”

I tried it again and the air ram misfired. So I told the guy that owned the air ram, “I’m not doing this. Let’s call it off.” He said, “I think I can go get you another air ram.” Now it’s probably 2 o’clock in the morning. He loads up his truck and he goes all the way back to Burbank from Valencia, California, which is an hour-and-a-half drive, picks up another air ram, gets all the way back to us at about 4 in the morning, loads in another air ram. I do it four times on flat ground. It fires every single time.

I said, “Okay, let’s not disconnect or move anything.” Five guys picked everything up and put it on the end of the cliff, and I went out there, did the fireball explosion, landed in the airbag fine and everything was great. I would never do that one again and I would never ask anybody else to do something like that again. In today’s world, we would do it with a much smaller explosion and enhance the fire in the background with CGI, and also put the guy on a cable so he can never really hit the ground. Back then, we didn’t have the safety. The way we did it was the only way to do it.

The Matrix Revolutions (2003), Neo vs. Agent Smith

David Leitch, stuntman and director: Stunts take on different shapes and sizes and levels of complexity, depending on the discipline within which stunts are taking place. I, as a performer, did a lot of fight choreography and wire rigging and flying, bringing that Asian influence of Hong Kong wire work into Western films. I think there was a sequence on the Matrix sequel, The Matrix Revolutions, where agent Smith and Neo were flying in the air. I, with the stunt rigging team and the special effects team, designed the flying rig where Chad Stahelski and myself could fly and fight midair.

In itself, it wasn’t complicated — or it wasn’t as dangerous as other stunts. But the logistics and the technology and the innovation was probably one of the most interesting and challenging stunts that we pulled off. It was tons of complicated wire rigging and wire work every day in a harness, flying hundreds of feet in the air. How could we make this flying sequence look real, at the birth of the modern comic book movie — which those movies were.

Undisputed II and Undisputed III, gymnastics

Scott Adkins; producer, screenwriter, actor, gymnast, and martial artists: I had to jump over a bike and kick somebody off in Accident Man; it was quite a big bike to get all the way over the handlebars, and it was an end of the night shoot. I was tired. Things like that are difficult. I also did a stunt in Accident Man: Hitman’s Holiday where I got thrown out of the car, and I did a nice side somersault off a Jeep that was quite high in Special Forces, that looked really cool.

But the most difficult stuff I’ve done are these gymnastic-y type kicks. In Undisputed II: Last Man Standing, I run up a guy’s chest and then flash kick them, do a somersault and land. I don’t think I’d seen that move done before I did it. Can I actually do this? Of course, you’re not going to do it the first time you film it. You’ve got to rehearse it. You could slip off the guy and land on your head, and hurt yourself in a very real way. In Undisputed III: Redemption, I do this thing where I run — I’m gonna have to explain it like this [gestures with his pointer and middle fingers] — and there’s a guy behind me. I jump up, but I do a reverse somersault going that way and land on my feet, and then he sweeps me. That was a really difficult move to do on a flat surface that was slippery. First take, I just went flat on my back, and everyone’s silent. “No, I’m gonna get this!” There’s a lot of pressure, because you don’t want to spend too many takes doing it. The more takes you have, the more tired you guys are.

Speed 2 (1997), a Ducati lay-down

David Barrett, stuntman and co-executive producer of Blue Bloods: I had to do a lay-down on a 916 Ducati for Speed 2 and [director] Jan de Bont didn’t want me to have a helmet. I mean, the character didn’t. And I had to be in a short-sleeve shirt. The stunt was to lay it down in front of an oncoming bread truck going uphill on pavement. That was a tough one because I knew I was going to get scraped up, and in a stunt like that, you don’t want to hit your head, obviously.

Aside from not wanting to hit my head, with a motorcycle stunt, it’s really making sure your hands don’t get caught. So you put your thumbs on the grips and it’s a one-two-three beat. First, hit the back brake. Two, you slam the motorcycle to the ground, and three you push off from it.

I knew that I was going to have my arms exposed and my head exposed. I could put a pad on my hip and I put a little pad on the top of my left elbow. I was paying a lot of attention when I went down that I hit those two spots! If you hit the right spots you tear up the pads and your wardrobe. If not, you’re gonna hurt for a while.

We did it once, and I told Jan de Bont I could do a better job. I could get it a little closer to the bread truck. He said, “Are you crazy? That was good. We can move on.” We did it again, and yeah, I was a little cut up afterwards, but at a certain point it becomes your brand. This is my product. That pain lasts a few days maybe. That film clip lasts forever.

The Fast and Furious: Tokyo Drift (2006), a Tokyo Drift

Rhys Millen, stunt driver: One that stands out would be a Tokyo Drift, where we had a spiral parking structure and we had to slide up it and I was doubling the Drift King in his car. I thought that it was going to be easy. Once we started, I understood that I had maybe oversold what could be done. But we pulled it off. It took three takes. The second one was a little too overconfident, then I had to bail out on it. But take one and take two, I got it. It made it in the movie.

The reason it was so hard was that the entry point [of the parking structure] was very, very narrow with a curb sticking out. You couldn’t fluidly hit the angle and change the motion of the car, you had to come into the shot already in position, because as soon as the car appeared, it needed to be into its performance angle. Then the whole way up, the right front tire was scraping the curb and the left rear bodywork was scraping the wall. The commitment had to be there. That one stands out not only to me, but the audience latched onto it as well.

The Cookout (2004), a high fall through a skylight

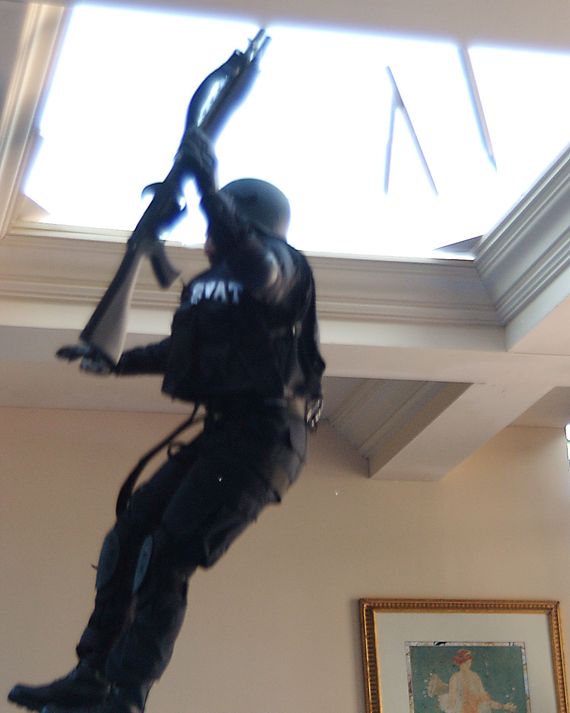

Cheryl Lewis, stunt performer: One of my favorite film stunts was a high fall through a skylight, for The Cookout. It was one of my first big stunt jobs in a film. Queen Latifah was in it, and I was doubling her. I’m not her usual double, but she was working on two films at the same time, and the schedules were overlapping, so they called me in.

They built a mockup of the house because they were on location at somebody’s actual house, so they couldn’t just smash through the real ceiling. In the movie, the character is wearing SWAT gear, so for the stunt I was wearing all that gear. As a gymnast, I have a pretty good sense of my body, and my location in a fall — we call it “air awareness” — but if the costume makes you heavier, it makes you fall faster. My job was to time falling through the glass, making sure I passed through the camera frame, before I turned my body into the safe landing position. If I turned too soon, the camera would see I wasn’t Queen Latifah, and if I turned too late I could get hurt.

What stuck out to me is that after I did it, one of the crew guys picked up a big chunk of the glass, and came over and said, “That was so cool, can you sign this piece of glass for me?” And I’m like, “I’ve never signed a piece of wreckage before,” but I gave him my autograph on a piece of the glass that I fell through.

Avengers: Endgame (2019), Captain America vs. Captain America

Daniel Hargrave, stunt performer: I did a couple days on Winter Solider. I went and doubled Chris [Evans] — that was the first I had ever doubled Chris and my first Marvel movie. I did Winter Soldier and then I was on Captain America: Civil War and then I got to do the additional photography on Thor: Ragnarok, and the last two Avengers.

The whole [Avengers: Endgame] sequence, honestly, that was kind of [my brother] Sam [Hargrave’s] brainchild. He found out pretty early that there was going to be a pretty cool Captain America vs. Captain America sequence and even during Infinity War he had started brainstorming and thinking up sets, especially adding in all the stairwells and the glass, and the stuff to make it kind of something different — add a couple stair falls and crashes through glass.

We had a good amount of time, a couple of weeks, to sit there and come up with the choreography and the gags and think, what’s something we haven’t seen? What was something that would really make the audience go “ooh” or “wow.” The biggest thing we wanted to show was how Captain America evolved through time. His fighting style, and Sam was playing the newer Captain America and I was playing the younger, from the flashbacks, so my style was a little different from his. He turned a little more Judo and was kind of anticipating the moves — it was fun, just to sit in there and try to outsmart each other and think of something we hadn’t seen before.

They did actually cut out a whole fight that happens inside of — there was this office that we smashed through after the big cat walk. It didn’t fit the scene, or it didn’t fit time-wise.

The double stair fall, where we just go flying down the stairs together and then we clip off the stairs in the rib … they built a big platform up top and everyone was watching. Sam and I go, “Alright, here we go,” and I jumped as far I could. I went first and I went slamming and fell off into some boxes. It was pretty amusing to watch two brothers just living it up, acting like kids.

Sam Hargrave, fight coordinator: We worked really closely with visual FX to design this space. I was with them from conception to building. I said, “You know, I think this gap should be eight feet rather than 16 feet, because it’s gonna be harder for our stunt guys to get from here to there.” It was a whole amazing experience just from the ground up, literally building this set, designing the action, coming up with the choreography, working with the Russos.

I always try to approach action and fights from a place of character and story, so you gotta find out who’s in the fight, where are they at this point in the story, where have they come from, and where are they going. It’s very similar I think to how I think a director or an actor would approach a scene like that, when you’re choreographing fight. The unique challenge about this was Captain America was fighting himself but from the past, so we have a certain set of skills that we’ve shown in the past that Captain America uses, a skillset that he has, and then how does the older, “wiser” Cap deal with these skillsets.

Usually I’ll work with the writers [on the choreography] and we do just kind of a pass. The guys are really into the story and knowing where these characters are coming and going, what beats do we want to hit? What important character moments do we need to hit along the way? And often times that’s set out in the script already. Then we kind of do a breakdown of that. I really enjoy the energy of other people and the kind of creative flow, the improv. I start with, “Okay, throw a punch, just throw a punch at me.” Then, you know, we’ll trade positions, like, “Okay, now wait I’m going to throw a punch at you,” and then [I] see what he does or she does and whatever they do — “Oh, maybe that’s better.”

I mean we were very fortunate at this point that it was almost as if the same person was fighting [in Endgame], because I was fighting my younger brother and we’ve grown up together doing, you know, fight scenes together, playing together, just being around each other our whole lives. But then the, you know, interwoven within that synergy is the relationship that Chris Evans and I have, and now Chris Evans and my brother, Daniel, because he doubled him on Infinity War. We do move almost as one person when we are in the suit, and my brother is very astute at picking up those kinds of things.

Chris would do both sides of the fight, so they take his face elements from one side and put it on one of us, my brother or I. So it’s Chris fighting me at some points, it’s Chris fighting my brother at some points, but then for the audience, it’s always Chris fighting Chris. It’s always Captain America fighting Captain America. It’s a very complicated fight sequence but I think all the math and science paid off in the end with a really exciting sequence.

With additional reporting from Tolly Wright.

For any other stunt performers who have a great hardest stunt story to share, let us know at stories@vulture.com.