A lot can change in ten years, including the culture we think is good. In the spirit of a new year, new decade, and new beginnings, we took a look back on how we’ve grown in ways we didn’t expect in the 2010s.

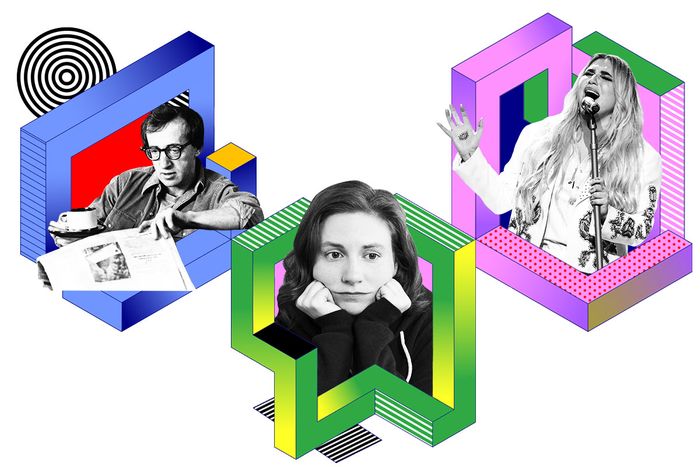

Girls

If you told me that I would be writing about the aggravating brilliance of the first season of Girls as civil society craters into a ditch, I would have started a futures market on my left kidney during the Obama era. After watching the pilot in 2012, I studiously avoided the show; it was like a dancing plague that made people collectively go insane, and I wanted to be disease-free. It was impossible to ignore the discourse — that it was white and privileged, and that Lena Dunham seemed to think herself the voice of her generation — but that seemed like enough reason to skip it. But before the final season, at the behest of my editor, one of the handful of people who can make me reconsider something, I finally started to watch the show. I got it. It was addictingly written and clearly self-aware (Dunham’s own high jinks notwithstanding), and an early prestige-TV example of a compelling and unlikable woman.

The first season is fantastic, in particular, because it felt true: White girls who live in hermetically gentrified pockets of Brooklyn are absolutely annoying as hell. (Girls became noticeably worse when it actively tried to address its “diversity problem” by including black people to embarrassing and retrograde results.) Episode seven “Welcome to Bushwick a.k.a. the Crackcident” is a great fulcrum for the arc of the season: Hannah (Dunham) sees Adam (Adam Driver) at a warehouse party and the viewer realizes just how unreliable a narrator Hannah has been this entire time. Adam might not just be the weird sex guy, but perhaps was just responding to Hannah’s own narcissistic fantasies. Then there’s the fight between Hannah and Marnie (Allison Williams) where each accused the other of being “a wound,” which demonstrated Dunham’s talent at depicting relationships in various states of disintegration. Girls was often at its best when its characters were at their worst (Marnie singing Kanye; the Hamptons episode), and who couldn’t relate to that. —E. Alex Jung

Kesha

Look, I’ve written some rude-ass things about Kesha, née Ke$ha, on the internet, some but not all of which have been thankfully lost to the ever-shifting waters of the online media-sphere. (RIP, the A.V. Club local editions!). And some of them I stand by, particularly in the context of her early 2010s “Get Sleazy” phase; I had a hard time wrapping my head and eardrums around the singer-songwriter’s “omg I’m so snotty and I don’t give a fuuuuuuck” vocal affectation and posturing, which was difficult to reconcile with my own personal standards for pop stardom. That stance became a little harder to maintain mid-decade, as her personal and legal struggles involving producer Dr. Luke gave us a bigger picture of what Kesha was going through as both an artist and a human being during that time. But 2016’s Rainbow was my Kesha “aha” moment, a clarifying document of what she has to offer — real songwriting chops and a voice that is not just powerful but, more importantly, interesting — and what she has to say when not stifled by a calculated trash-can-princess persona. It wasn’t a complete stylistic 180, but it was a marked evolution that also helped me recalibrate my feelings toward her earlier work; it’s easier now to see the “real” Kesha struggling to be heard in those earlier songs I initially dismissed. I get it now, and I’m sorry, Kesha. I can’t wait for High Road. —Genevieve Koski

Walking With Dinosaurs

In 2013, 20th Century Fox released Walking With Dinosaurs, a feature film inspired by the popular 2000 BBC docuseries of the same name, which was notable for its impressive CGI dinosaurs. The movie told a familiar-sounding underdog story about a hapless but adorable pachyrhinosaurus voiced by Justin Long, with a framing device involving two modern-day kids being lectured to by a wise-ass crow turned prehistoric parrot voiced by John Leguizamo. I watched it late one Thursday night, so I could quickly turn around a review for the next morning. I was not kind: The film seemed lazy, alternating between lowest-common-denominator gross-out jokes and uninspiring dialogue that sounded downright weird coming out of the mouths of photo-realistic dinosaurs. That weekend, however, I saw the film with my 4-year-old son, who was obsessed with the prehistoric creatures. He loved it, of course.

Now, my child loving something I didn’t is nothing new, and it’s happened plenty of times since (I’m looking at you, Emoji Movie!) But something about Walking With Dinosaurs hit him hard; he was a tearful wreck by the end. And I started to see the movie with new eyes. That seemingly silly framing device, which highlighted the fact that these creatures were no longer around anymore, suddenly had a melancholy quality — an idea hammered home by the film’s closing images of a herd of dinosaurs vanishing into thin air. The standard-issue tale of loss and overcoming, which included a dark scene featuring our hero’s father’s death, clearly clicked with my son, who grabbed onto me during the scene. Even the half-hearted animation of the dialogue — the dinosaurs’ mouths never quite matched the words, giving their exchanges a weirdly insular, unreal feeling — gained a strange power: It made the movie feel like we had stepped into the imagination of a child. I started to warm to the film. We actually went and saw it three more times in theaters, and continued to revisit it on DVD for years afterward. I look back at my review of the film now and see that many of the things I’ve come to love about the film, I singled out back then as problems. The Emoji Movie, however, remains terrible. —Bilge Ebiri

Post Malone

If there was one white rapper I’d end up doing a 180 on by the decade’s end, I’m glad it wasn’t Macklemore, Iggy Azalea, or … Kreayshawn? It’s outrageous to think Post Malone launched on the scene only midway through the decade, in 2015, with one of SoundCloud’s first big hits, “White Iverson,” a rapish, R&Bish, popish slurred-sung woozy thing from a white boy sporting a gold grill, cornrows, a raggedy beard, and tinted shades. He resembled something like a less flashy, more sensitive James Franco cosplaying as Riff-Raff in Spring Breakers. His music was depressing, charismatic, and deeply popular for both reasons, though Posty courted controversy for playing fast and loose with rap while fumbling through how to explain being a white Dallas-raised kid with diverse influences, and arguably lacking depth. (Eminem and the Beasties Boys, by comparison, were much better at this conversation.) By 2019, though, something’s grown clear about Post Malone: He never thought any of it required explaining. To Posty and a lot of other 24-year-olds, genre-mixing comes naturally. And unlike Miley Cyrus’s own genre journey, it isn’t as opportunistic; his stadium rock, metal, rap, country, folk, and pop roots all jell and maintain a presence throughout his increasingly improved catalogue. Now he’s collaborating with Ozzy Osbourne and Travis Scott on the same track; he’s ditched the braids for tousled curls and cowboy hats; traded all-black bummy fits for rhinestone-encrusted baby-blue suits; and become one of the most-streamed artists of music streaming’s infancy. Luckily, some things haven’t changed: He’s still got his Bud Light and charm. —Dee Lockett

Smash

When I first watched Smash, I thought it was terrible. Terrible! It made so many decisions that undermined its own project — not just the sin of insisting that Katharine McPhee was a better Marilyn Monroe than Megan Hilty, although that was the first and most unforgivable sin. But the stories about developing Bombshell (the musical about Marilyn Monroe) that never included enough of Bombshell, the insistence that Katharine McPhee was sympathetic, everything to do with Debra Messing’s character, the weird plotting. It was all a mess and I hated it.

I have watched and love many shows since then, and there are not many I think about more than I think about Smash. Part of it is that Smash now fits in my mind as a kind of television I really treasure: the audacious failed experiment. But it may just be that I now think Smash is actually good. It’s still a nightmare in lots of ways, but the idea that McPhee could be universally accepted as the better choice while Hilty is there, consistently perfect, is something that now seems like a meaningful tragedy rather than a mistake. The Hiltys of the world deserve better, and Smash is a story about how they deserve better. No matter how good they get, someone just keeps moving the line. —Kathryn VanArendonk

Random Acts of Flyness

When I originally reviewed HBO’s Random Acts of Flyness I wasn’t on the right wavelength to receive its striking deconstruction of form and sense of play. As I wrote then, I found it to be “dazzling but emotionally inert.” But in rewatching the series over a year later, I found myself more than just enthralled. I was challenged by its dynamic experiments with what a sketch show can be as it delved into police brutality, sexuality, desire, and racist violence through a distinctly black lens. —Angelica Jade Bastién

Woody Allen

Sometime in the first half of the decade, maybe six months or so into dating the man who would eventually become my husband, I remember going on a hike with him and talking about great work made by bad men. “I still love Woody Allen,” I declared. I remember the little transgressive thrill I felt: I was telling him that I wasn’t one of those women, the sort who’d let a man’s monstrous behavior get in the way of appreciating a cinematic masterpiece like Manhattan, or one of the greatest romantic comedies ever made, Annie Hall.

It’s not that my principles have grown more noble; for better or worse, I still love Marnie, though I’ve read all about how Alfred Hitchcock tormented and harassed Tippi Hedren throughout the production of that film. It’s that in this revelatory era, Allen’s work itself feels different, leached of its romantic allure. His appeal as a leading man always hinged on his ability to portray himself as a harmless, bumbling underdog. But this afternoon, when I tried to watch Annie Hall and Manhattan, I could only see him as domineering and difficult, a man whose powers of seduction rest on his skill at cutting women down and making it look like charm. When you see the magician palming the coin, the thrill is gone. —Lila Shapiro

More From This Series

- Who Was the Best New Artist of the 2010s? Vulture Investigates

- The Decade in Theater: Six Closing Thoughts

- 103 Days That Shaped Music in the 2010s