In another strong year for books written by women, we see the return of Elena Ferrante, a magical battle for the soul of New York, and a Me Too narrative unlike any you’ve read before.

In Kiley Reid’s first novel (and late-2019 entry), a young black babysitter takes a white child on an evening run to a fancy supermarket in Philadelphia. When a security guard accuses her of kidnapping the kid, it sets the stage for what the New York Times called a “provocative but soapy” exploration of race and class and what it means to raise someone else’s children. Lena Waithe, who has already acquired the adaptation rights, hailed it as “a unique, honest portrayal of what it’s like to be a black woman in America today.” —Lila Shapiro

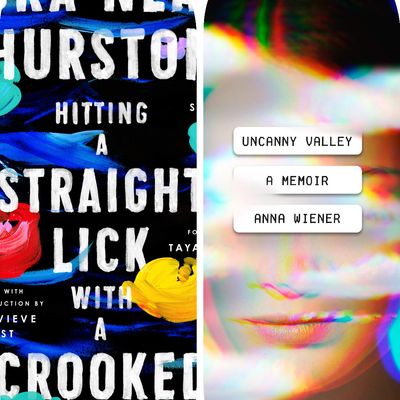

With the landmark 2018 publication of the novel Barracoon, written nearly a century ago, Zora Neale Hurston came back into hearts and minds and best-seller lists as one of the foremost writers on the black American experience. For the completist, this story collection, which includes eight previously unpublished stories that come from the days when Hurston was the only black student at Barnard, is a can’t-miss. —Maris Kreizman

If you read gay literary phenom Greenwell’s last novel, What Belongs to You, think of this as a sequel that doesn’t let chronology worry it. Cleanness picks up the story of that same unnamed American man teaching in Bulgaria, and in nine pieces — what Greenwell has called a “lieder cycle,” the classical-music term for a novel-in-stories — dances and dips around the intimate moments that have shaped his life abroad. Look forward to more of the exquisite, high-wire sex writing that has earned Greenwell his reputation. —Hillary Kelly

Anna Wiener left her book-publishing job to pursue a career in tech back when start-ups were revered for their possibilities, all IPAs and cold brew on tap and open-plan offices filled with precocious future billionaires still dressed as children. If the literary world was all about paying one’s dues and respecting a rigid hierarchy, then Silicon Valley was 24-year-old bosses with major holes in their knowledge and experience who nonetheless controlled the fates of many. In this cutting, gossipy memoir, Wiener details how the absurdities of the culture of tech companies helped to mask larger, looming problems: the lack of regulation that allowed tech companies to amass monstrous amounts of wealth while eroding the privacy of ordinary citizens. —MK

Charles Yu is a science-fiction writer who recently made the transition from books to screenwriting (Westworld), so it’s fitting that his inventive latest novel is written in the form of a TV script for a Law & Order–style crime show. Television is a more than apt metaphor for the roles we aspire to and get to play in society, and Yu plays with the analogy to great effect. The novel’s main character, Willis Wu, is a Taiwanese-American man who longs to one day play Kung Fu Guy, but so far has been limited to playing characters such as Disgraced Son, Delivery Guy, Striving Immigrant, and Generic Asian Man. Can Willis ever land the leading role in his own life, or is he doomed to forever have a bit part in American culture? Both whimsical and profound, Interior Chinatown is a bildungsroman for the binge-watch generation. —MK

I’m terrified. Worry fills every empty pocket of my days — rising seas, rising fascism, lowering morale. Jenny Offill, and her magnificent new novel, Weather, get it. Oh boy, does she get it. Weather is the story of Lizzie, a librarian tripping around through modern life, answering emails for a mentor’s advice podcast (brilliantly called Hell or High Water) and slowly collapsing inside her own fears. Told in exquisite, perfectly shaped fragments (“Young person worry: What if nothing I do matters? Old person worry: What if everything I do does?”), Weather is a book of prayer and a Book of Revelations. — HK

The latest from Aravinda Adiga, whose 2008 The White Tiger won the Man Booker, Amnesty tells the story of an undocumented immigrant, Danny, living a relatively quiet life in Australia after being denied refugee status as he fled his native Sri Lanka. (Danny is a Westernization of Dhananjaya Rajaratnam.) Things take a turn after he finds himself in the middle of a murder case and speaking up could mean deportation. Amnesty is a story that will, with plenty of Adiga’s trademark wit, force you to reckon with your own ethical code. —Madison Malone Kircher

Brandon Taylor is a writer who really gets the indignities of inhabiting a human body, how the physical is so intimately tied to the emotional, especially if one is in turmoil. His debut novel follows Wallace, a black, gay biochem grad student at a midwestern university, over the course of one long weekend filled with loneliness and shame, hot feelings and hot sex, anger and repression. Wallace keeps getting in his own way in his academic life as well as his love life even though he has enough to overcome already (see “black, gay biochem grad student at a midwestern university”). Wallace is a heady mix of judgmental and vulnerable, and it’s hard not to root for him even if he decides to blow his life up. —MK

The vampire genre has been dead for years. In his 2017 novella, Small Changes Over Long Periods of Time, the queer and trans author K.M. Szpara managed to give it new life. Now he’s written a novel about a young man who tries to save his family from debtors’ prison by selling himself to a handsome trillionaire. No less of an authority on the macabre and subversive than Carmen Maria Machado has lauded it on Twitter. “Disturbing, kinky & queer af,” she wrote. “It is very upsetting but I promise you will tear through it.” —LS

National Book Award winner Louise Erdrich has been drawing inspiration from her Chippewa heritage since the 1970s. In her latest, the titular protagonist is based on her grandfather, who, as chairman of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians in North Dakota in the 1950s, fought against the Termination Act, an effort by the U.S. government to continue its long-standing tradition of grabbing Native lands. Three years after Standing Rock, the story of that fight feels as urgent as ever. —LS

Think about your favorite ’80s teen movies, and then think of all the ills they perpetuated — the casual racism and the slut-shaming, not to mention the homophobic stereotypes. We Ride Upon Sticks is a novel that captures the giddy fun of your favorites — the wild parties and the teased bangs, the outsiders with the witty one-liners and the thrill of winning the big game — but it also breaks apart the myths of ’80s teen tropes by putting the story in context. As narrated by the 11 members of the Danvers Falcons women’s varsity field hockey team in 1989 and in the more enlightened present day, the novel follows the team’s meteoric rise from mediocrity to the state championship after signing their names in a powerful, potentially witchy notebook with Emilio Estevez’s face on the cover. —MK

Euphoria, King’s sensuous and potent 2014 novel about anthropologist Margaret Mead and the pseudo-biographical love triangle she bounced around in between her second and third husbands on a daring river expedition in New Guinea, established King as one of our greatest writers about desire. Her next novel, Writers & Lovers (set in 1997 Harvard Square), follows a hopeful young novelist into her own love triangle — between two men, yes, but also between romantic love and her thirst to prove her writing chops, and between memories of her dead mother and a brighter future that she can’t quite will herself to believe in. This novel will become a defining classic for struggling young writers. —HK

In Kate Elizabeth Russell’s lyrical and propulsive debut novel, a woman in her 30s learns that the English teacher with whom she had a sexual relationship when she was 15 has been accused of sexual assault by another former student. That may sound like a familiar premise in Me Too era, but the story quickly veers into bold and unexpected territory, with the protagonist calling her teacher and asking him to recount their sexual encounters while she masturbates. It’s the fearlessness of such narrative choices that prompted Stephen King to call the book a “well-constructed package of dynamite.” —LS

These days it’s easy to forget how weird and wonderful the internet can be, how online communities were once a place to make real, lasting connections before the corporate overlords took over and sanitized them. In his debut novel, Kevin Nguyen captures both the magic of online culture and its numerous, ever-increasing dangers. Fast-paced and sleek like the latest tech device, but with a beating heart and soul as well, New Waves is a skewering send-up of start-up culture and a deeply felt exploration of friendship and identity in the digital age. Nguyen deftly explores who technology is for, who uses it, and who profits from it, and how hard we grapple to bridge the disconnect between our ambitions and ourselves, our avatars and our actual flesh. —MK

Throughout her rich body of work, essayist and critic Rebecca Solnit has revealed pieces of herself in writings about the beauty of getting lost, the joys of walking both for pleasure and with purpose, and perhaps most famously, the indignity of being mansplained to. At last, she uses her eagle eye to explore her own life. Recollections of My Nonexistence is a marvel: a memoir that details her awakening as a feminist, an environmentalist, and a citizen of the world. Every single sentence is exquisite. —MK

Nobody yet has their hands on the final installment of Mantel’s double Man Booker–winning Thomas Cromwell trilogy. But I don’t need a copy to tell you that The Mirror and the Light — which follows Cromwell from the immediate aftermath of Anne Boleyn’s death, through Henry VIII’s marriage to Jane Seymour just ten days later, her subsequent pregnancy and death, and straight through till Cromwell’s own beheading — will have us sitting up in bed until 3 a.m., pouring over Mantel’s remarkable world-building skills, and sobbing that one of the century’s best series has concluded. —HK

N.K Jemisin’s last trilogy was set on a continent called the Stillness, a world rent by earthquakes, covered in ash, and dominated by a racist political system. With The City We Became, she turns her attention to another cruel and oppressive realm — the gentrifying neighborhoods of her hometown, New York City. I’ve been looking forward to this story of a magical battle for the soul of New York ever since I accompanied the famously meticulous author to a park in Inwood where she gathered details for a scene. —LS

Readers of Emily St. John Mandel’s post-apocalyptic hit Station Eleven (and there are, at last count, at least a few hundred thousand of them) will be delighted to learn that her next novel operates in the same universe as the one in which a “Georgian flu” wiped out over 99 percent of the world’s population in just a few weeks; The Glass Hotel is set years before all that action, but it’s just as riveting. It kicks off with a woman tossed overboard from a shipping freighter and a bizarre act of vandalism at a remote Vancouver Island hotel, and then delves into a long- tentacled Ponzi scheme that eats up the lives of everyone it touches. If Station Eleven made Mandel a phenom, The Glass Hotel will solidify her as a defining cross-genre talent. —HK

Hex is the sort of novel that almost has its own smell — humid and loamy, like a body after a morning spent bent over a garden patch. It’s about Nell Barber, a recently expelled Ph.D. student secretly running her own experiments on poisonous botanicals in her apartment and vigorously lusting after her buttoned-up adviser and mentor. Sex practically pulses out of Nell as she fails her way into adulthood in this botanically entwined work of early-adult dissatisfaction. —HK

A breakthrough voice of the previous decade, Sam Irby is poised to reign in the 2020s. Her takes on the absurdities of everyday life means that she can write about reality TV, poop, frittatas, and mental-health meds with equal aplomb. Her latest essay collection includes her attempt to have a wild night out, the ideal songs on her late-1990s mixtape (she likes Dave Matthews, so what), and a chapter called “Lesbian Bed Death,” in which each sentence starts with “Sure, sex is fun, but …” It’s been a joy to watch her build the strange confidence that comes from being comfortable with her own insecurity, a feat that few writers get to achieve. —MK

God glitter is just about the only thing that’s abundant in the California town of Peaches, where a drought has killed crops and dulled the landscape. Its citizens need a miracle to bring rain back to the land, and many put their faith in a charismatic pastor with a penchant for wearing sequined capes and tossing around gold drugstore glitter as if it were holy. Godshot is a piercing debut novel filled with devastating imagery (sticky baptisms performed with soda instead of water) and a girl named Lacey May Herd who is brought up to believe that suffering brings you closer to God. When Lacey May is forced to live with her grandmother after her troubled mother abandons her, she must reckon with the pastor’s grand plan for Peaches and the damaging ways we choose to satisfy our thirsts. —MK

Literature’s reigning queen of the profane, Ottessa Moshfegh is divisive: Readers tend to love her or hate her. If her latest novel is subtler than her most recent works, it’s just as chilling — it could be a jumping-off point for new readers. A self-contained horror story that takes place inside the mind of an alluringly unreliable narrator, the novel follows a 72-year-old widow who has moved with her dog to a large plot of land where they are seemingly at one with nature. When she finds a handwritten note that implies a murder has taken place on her property, she works to solve it as best she can. The narrator’s dark fantasies and less-than-pure thoughts work especially well if you think of Death in Her Hands as a sequel to Moshfegh’s deliciously gross and grotesque debut novel, Eileen. —MK

A nonfiction work from the Pulitzer-nominated author of last year’s The Other Americans, Laila Lalami’s Conditional Citizens uses her own story as a Moroccan immigrant to the United States to delve into what it means to be an American citizen and the rights and protections that come with it. The book opens with her naturalization ceremony and tackles the fraught relationship between citizenship, where you’re from, and what you look like. —MMK

Charlie Kaufman is the rare screenwriter who is as celebrated as the directors who have brought his mind-bending scripts to the screen. Now he’s a novelist too. Antkind follows a failed film critic who stumbles across the greatest film of all time — a three-month-long, stop-motion masterpiece that took 90 years to make and has since been destroyed, save for a single frame. If you loved Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, I shouldn’t have to tell you anything else to convince you to read it. —LS

There isn’t enough true weirdness in literary fiction today — writers willing to follow unimaginable narrative trails into the most hidden aspects of humanity. But Catherine Lacey, who blows my mind anew with each surreal, tightly controlled novel, is one of the true freak rogues. Her next novel, Pew, about an uncategorizable stranger (genderless, racially ambiguous, and silent) who shows up in a small town and first bewitches and then upends the community, is just the right kind of bizarro tonic. —HK

A serial-killer novel that’s almost entirely unconcerned with the murderer’s methods and motivations, These Women instead puts the spotlight on five of the women around him. They’re the ones who get backstories and interior lives and desires, because they’re the ones whose narratives are so often obscured. In 2014 in South L.A., young black and Latina women are being killed in a style very similar to a string of murders that took place 15 years prior, when the victims, most of whom were sex workers, were deemed low priority for law enforcement. Pochoda’s unconventional crime novel probes whom we listen to and why, and whose voices are deemed worthy of being heard. —MK

Utopia Avenue is, according to Mitchell, “the strangest British band you’ve never heard of,” and the subject of this late-1960s-set, 600-page tome, which is reportedly filled with everything worth reading about — sex, psychedelia, and stardom. No word yet on whether its structure folds in on itself, like the novelist’s 2009 megahit Cloud Atlas, or returns to more linear forms of storytelling, like his 2006 bildungsroman Black Swan Green. Either way, it’ll be a publishing event and will most likely suck you right in. —HK

Before she was a best-selling novelist, Brit Bennett was gaining viral fame for her searing critical essays about race and privilege in America, like her Jezebel piece “I Don’t Know What to Do With Good White People.” Her second novel (after 2016’s excellent The Mothers) is about estranged twin sisters, one of whom is secretly passing as white. —LS

Grazie dio! I slapped my hands over my eyes reading the reviews out of Europe of Ferrante’s first novel after the conclusion of the girlhood-affirming Neapolitan quartet — how could she possibly match the piercing yearning that had characterized that series? But critics are delighting in The Lying Life of Adults, another Naples-set bildunsgroman of a disenchanted young girl on the cusp of womanhood, though this time it’s set in the 1990s among the intelligentsia. Reader, I must confess, I’m so excited that I’ve ordered myself a copy of Lying Life in its native language, which I’ll be slowly working my way through with the help of my trusty college Italian dictionary until an English galley arrives. —HK

More than anything, Lynn Steger Strong’s Want is a reader’s novel, which is to say that it is rife with mentions of other novelists (Jean Rhys, Iris Murdoch, Doris Lessing, Anita Brookner) and both indebted to and an homage to their work. It’s the story of Elizabeth — a want-to-be professor turned high-school teacher headed for bankruptcy with her Wall Streeter turned furniture-maker husband and their two little girls — who can’t stop herself from slipping away from her life and getting lost inside fictional worlds. Meanwhile her real world, of inertia and continual catastrophe, continues to unfold against the backdrop of our steadily unraveling country. —HK

Why, oh why, didn’t I read Homegoing, Yaa Gyasi’s debut novel, which I saw on a million bookstore tables and somehow never took home? Regardless, I’ll be digging into it now, after reading her follow-up, Transcendent Kingdom, about Stanford neuroscience Ph.D. candidate Gifty, who takes in her depressed, devitalized mother and reexamines the undoing of her family after they emigrated from Ghana to Alabama. Gyasi has the lightest touch on the page and yet her writing wiggles its way into your dreams. —HK

My dad spent a summer enmeshed in Susanna Clarke’s thousand-page fantasia of Regency English magick and has not stopped asking me when she would put out another book ever since. Finally, 16 years later, that day has come. Piranesi will be slim (Amazon claims 180 pages), but its premise, about an infinitely corridored house of Borgesian proportions and the man who wanders its rooms, practically guarantees that Clarke will be back at her masterful world-building — even if this time there are no footnotes. —HK