Out of the theme park and into the penthouse: Westworld has gone urban. In its third season, HBO’s sci-fi series about a rebellion of gym-toned robots plays out in cities that shape-shift and merge. The show was shot largely in Los Angeles, Singapore, and Spain, and locations were then melded with the insertion of imaginary skylines. The cinematography applies a uniform coat of shellac so that physical places resemble architectural renderings and digital architecture looks almost real.

Westworld’s third season was filmed in 2019, the year that, in the original Blade Runner, Los Angeles was supposed to have turned into a layered megalopolis — market-choked Asian capital at street level, jet-stream-level offices above. This new iteration offers a different kind of mash-up, mixing downtown L.A. and real-life Singapore, plus a scattering of fictional buildings. The creators tapped Bjarke Ingels, one of the most future-drunk architects around, to consult on the city’s shape; he raided his firm’s cemetery of unbuilt designs and sprinkled them around the skyline. Far-out structures, both extant and notional, flash by in a sequence of look-at-that! moments. It’s as if you had a crowd of extras populated by movie stars.

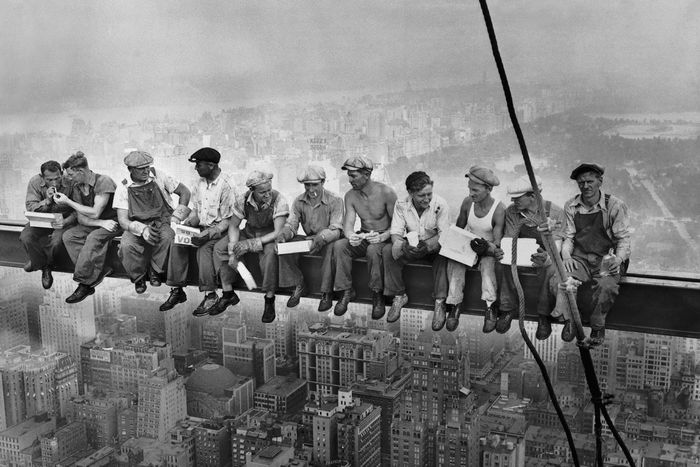

In the first episode, Caleb (Aaron Paul), a construction worker who spends his days erecting a future version of downtown L.A. and his nights as a petty criminal for hire, drives over the Art Deco Fourth Street Bridge (the new Sixth Street Viaduct, an L.A. landmark-to-be, is still under construction) to MacArthur Park, where a skyline of tilting, twisting, and snaking forms glimmers across the lake. A few minutes later, he’s walking on Singapore’s pedestrian Helix Bridge, an architectural-scale expression of a strand of DNA, lit by blue and purple LEDs.

This deluxe dystopia, agleam with prosperity and gentrified to a high polish, is the latest in a long line of meticulously fantasized urban futures that tell us more about our own dissatisfactions than any real leap of the imagination. Filmmakers hardly need to make anything up, since real-life architects and planners are constantly imagining future versions of the cities we live in, projecting today’s desires and anxieties onto richly detailed fantasies. In these best of all possible worlds, everything always works, and reason always prevails. “It almost looks like it makes sense from up here,” says the information tycoon Liam Dempsey Jr. (John Gallagher Jr.), gazing down over Santa Monica from an airborne drone like a master planner beholding a foam-and-balsa model.

It takes a lot of organized violence to preserve that rational veneer. Ingels told me that he was the one who suggested they give the role of future L.A. to Singapore, quoting the sci-fi author William Gibson’s 1993 article for Wired, which famously described Singapore as “Disneyland with the death penalty.” Singaporeans, having created a physical city that was livable, fantastical, and repressive, proposed to generate “a coherent city of information, its architecture planned from the ground up,” Gibson reported. Success, he went on, would prove that it was “possible to flourish through the active repression of free expression. They will have proven that information does not necessarily want to be free.”

More than a quarter-century later, all major cities, in democracies and dictatorships alike, are subsumed within a global metropolis of digits that transit effortlessly across thousands of miles, ignoring distance and cultural difference. In Westworld, the camera does the same, slipping with ease from one striking but chilly spot to another: the Delos headquarters, played by the City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia, a campus of crouching white-steel creatures designed by Santiago Calatrava; the Southbank Centre on the Thames, with the London Eye and Big Ben winking in the background; a subway system so sparkling and empty it looks like a pandemic has blown through.

Starting a scene on one continent and finishing it in another isn’t exactly a miracle of filmmaking. But the ease with which various onscreen cities fuse reflects a foundational reality of contemporary life: Data, Westworld’s true protagonist, goes where it pleases. More implausibly, characters do, too. There are no traffic jams or grueling commutes in this boundaryless city, just plenty of mobility options: pilotless taxis, aerial drones (silent and clean), and elevated walkways. A few old-fashioned bicycles glide by on clear, smooth bike lanes. Pedestrians claim plenty of street acreage as their own. The private automobile hasn’t quite disappeared, though. When crisis strikes, Liam Dempsey dives behind a sports car’s steering well and rumbles away. Dolores, eager to catch up, speaks to the great brain that dwells in all things, instructing it to “find me something fast. Now.” Fortunately, there’s a bike-share station handy, stocked with a sleek, silent, electric, app-based Bat-type two-wheeler that travels at roughly 80 miles per hour and handily valet-parks itself.

All these modes of transportation make an appearance, not just because of a sci-fi thriller’s perpetual need for speed and various ways of achieving it, but because the ideal city, even a deeply corrupted one, must make it easy to move around. In our world, the coronavirus-induced halt in travel has shocked us all: the segment of society that rides the subway to work each day, no less than those accustomed to hopping from capital to cosmopolitan capital and waking up in the morning unsure of what the local language is. As we’ve discovered in the last couple of months, that speed is double-edged. It’s not just people or data (and its associated “viruses”) that go whipping around the world, but much more primeval bits of code that inhabit our bodies and make them fail.

Westworld’s deceptively human protagonists are creatures with sleek façades that sometimes peel back to reveal the machinery that makes the whole system work. In the show’s architecture, too, steel and nature intertwine. In the camera’s jaunt through Singapore, tropical greenery climbs up and spills from high-rise hotels like the Parkroyal on Pickering and the Oasia Hotel. The show has commandeered the School of the Arts for use as a hospital, where the antiseptic shine of the interiors contrasts with an exterior furred with creepers. Among the Ingels designs that make a background cameo is CapitaSpring, a “spiraling vertical park in the middle that bursts out of the façade,” in Ingels’s description. These garden-skyscrapers are partly the result of climate-conscious fashion, popularized by the Milan-based architect Stefano Boeri, and partly the result of Singapore’s idiosyncratic zoning regulations, which promote high-rise greenery. But here they act as a kind of inanimate Greek chorus, commenting on the parade of beautiful people and the primal, unthinking energy that lurks inside the wrapping.

There’s something invigoratingly creepy about the sight of tropical nature muscling through a steel skin or invading a right-angled space. In Maurice Sendak’s classic children’s book Where the Wild Things Are, a forest in Max’s bedroom “grew and grew — and grew until the ceiling hung with vines.” That profusion is the signal for the boy’s raucous subconscious to roar out into the open. The Westworld equivalent of Max’s room is the brain of the wired universe, which appears later this season, and is encased in the intricate arrangement of concrete shells of Ricardo Bofill’s Factory, outside Barcelona. In the early 1970s, the Spanish architect overhauled a vast and decrepit complex that had once been a cement plant and turned it into his studio. A landmark of the structuralist movement, the Factory is a verdant estate, full of startling alleys, dead-end stairways, and lush gardens: a miniature city carved out of an industrial behemoth. In the show, a remote-controlled robot breaks out of the bunker, a wild, yet obedient thing hunting for its Eden.

Watching the show in the middle of a pandemic complicates the metaphor. Now, skins and surfaces — all those glass screens! — have become a global menace, too. Invisible danger doesn’t just lurk beneath; it lies right out in the open.