The version of Buyer & Cellar revived online by Broadway.com this week (and still accessible tonight until 11:59 p.m.) wasn’t just a good one-man show staged in a living room or just a benefit that raised more than $200,000. It was also one of those small-step-giant-leap situations, a little laptop-size window into a possible future. If predictions are right, mass gatherings might take a long time to return, so it’s a major relief to learn that a live (at least originally) home broadcast of a theater piece — not just a reading — can crackle like an in-person performance. So how’d they do it?

First, the caveats. The stars weren’t just aligned for the show — they were in military formation, saluting. Michael Urie already knew the show backwards; he originated the role, performing the play over 600 times in spaces as small as the Rattlestick Theater downtown and as large as the 1,600-seat Curran in San Francisco. By wild chance, he’d also recently been asked to perform it again (after years away from the part) for the Streicker Center at Temple Emanu-El on the Upper East Side: He and director Nic Cory had mounted what they call a “chamber version” as recently as February 23. The play itself was the right piece for the right time, too: Jonathan Tolins’s play is very much about isolation, so it was already on-point thematically, not to mention conceived as a direct address and set in a single room. It’s unlikely there’s anything else out there right at this moment quite so perfectly teed up for success. But if we see it, we can be it: Once theater-makers see how the digital form can work, they’ll exploit its strengths.

Here are the lessons that the team took away.

Pick the right technology. Broadway.com editor-in-chief Paul Wontorek was the digital director, the one in the control room (a guest room in the Catskills), making the live broadcast happen. Other video productions in quarantine had taught him to be a live-in computer editor: filming a daily Broadway.com news show, #LiveatFive, directing the shots for the starry Lips Together, Teeth Apart reading, and splicing together the hundreds of guests for the live Rosie O’Donnell Show. For the McNally play, he used Ecamm, Skype-network software, which had a number of advantages, like streaming at a higher definition. Ryan Spahn, the director of photography for Buyer & Cellar and Urie’s partner, likes Ecamm because it lets you blur speakers’ backgrounds, which gives a cinematic, painterly effect.

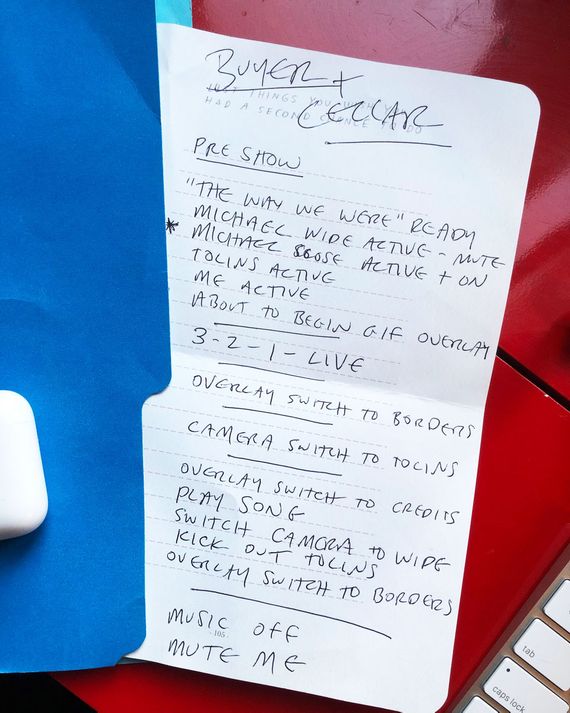

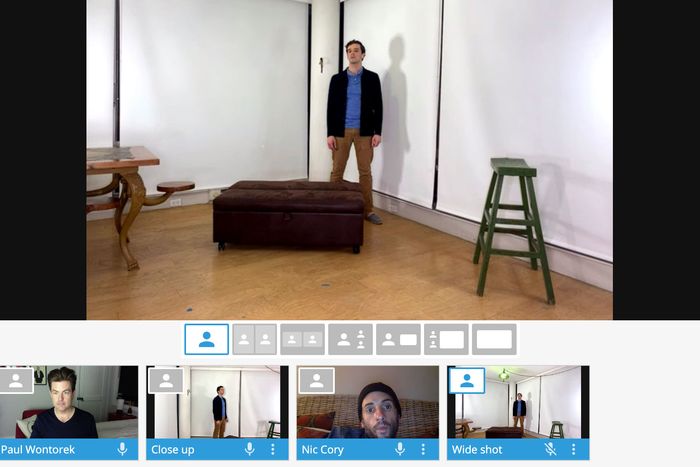

But Wontorek wanted something else for Buyer & Cellar. Very early on, the team had decided they needed a two-camera setup, a wide shot and a close-up, and the camera choreography between the two is a major key to the broadcast’s dynamism. (Lucille Ball and cinematographer Karl Freund worked out live multi-camera principles in 1951! Everything old is new again!) For this shoot, Wontorek used StreamYard, which allowed him to switch seamlessly between the feeds from the two iPhones in Urie and Spahn’s apartment — but only as long as both cameras were streaming all the time. (There was a “popping in” quality if they cued the feeds separately.) They found they were pushing the technology to its utmost: Some elements had to be animated GIFs that overlaid and obscured the live image, since there was no way to ever smoothly end or start a shot. Wontorek couldn’t fade a camera down for the blackout, for instance, so he used a five-second-long all-black video file as a kind of virtual curtain.

Keep it simple. As someone who has peered at every single bookshelf in every single Zoom meeting she’s been in, I can testify: A busy background wrecks concentration. Spahn says they knew they needed to neutralize the space, “get interesting with the position of the camera,” and find any place in the apartment that could offer a little depth. The set in the corner of Urie and Spahn’s apartment was therefore plain and stark — they pulled white shades down to the ground, hung a single light, and gave Urie two places to sit. Spahn and Cory obsessed about maximizing lighting so that the space became a kind of bright limbo, blown-out and featureless. (To get the look, Spahn used all the lights in their apartment, plus three ring lights, two of which were borrowed.) “I know what I do when I watch TV,” says Urie. “I look at my phone, and I’m also … judgmental. I will watch something until I don’t want to watch it. But in theater, you make a commitment! You don’t look at your phone. At least,” he hisses, “decent people don’t. So there can’t be anything to distract them. We don’t have to make it seem like we built a theater in the apartment, but it should be this other thing that doesn’t leave any room for distraction, not even a shadow.”

Wear AirPods. Wontorek was keen that the sound be great, and at first it wasn’t. At first they tried using the microphones on the phones, but as Urie moved around the tiny corner stage, he got closer to and farther from them, making the sound boomy and difficult to hear. Wontorek is himself hard of hearing; he also knew that when an audience can’t make out the words, they’ll tune out. Spahn found that earbuds work like lavalier microphones, so Urie wore his AirPods. After a few seconds, a viewer barely registers them. They offered consistency—though they didn’t always offer enough battery life, so there was some last-minute borrowing and swapping. But the audio was perfect. (Urie also recommends using the back-facing camera on your phone, since the quality is a little better and you don’t watch yourself.)

Rehearse. This isn’t news, but it’s still key. As an actor with wide experience both onstage and onscreen, Urie needed to get accustomed to a hybrid style that was part theatrical (big, physical, intense) and televisual (no need to shout, using the eye of the camera to stand in for an entire audience). “Because I was miked,” he says, “my physicality was the same, but my vocal effect had to be quite a bit less.” He found himself drawing on both sides of his acting training — how to pitch a text for a “big audience over there” and a “tiny audience right here.”

And also, rehearsal will tell you when disaster might strike. The day before the shoot, a plan to use pretaped introductions from Urie and Tolins went sideways. For some reason, in StreamYard, changing from a recorded welcome to the live shot delayed the sound — and hours of troubleshooting couldn’t fix it. At 11 at night (the dress rehearsal was supposed to start at 8), they realized that they’d have to do the intros live. Yet another rehearsal discovery: Battery life is … life. Spahn acknowledges, with dignity, that in addition to being director of photography, monitoring sound, and wrangling a slightly nervous part-Chihuahua named President McKinley — he was also in charge of the phone batteries. Nothing could charge during the show since it caused feedback in the AirPods, so everything was plugged in until just before showtime. (Phones also sometimes stop recording video when they get down to 20 percent, so … prayers up. If you have one of those extra-battery-life packs that straps onto your phone, use it.)

Mark your space. The group found that there was a very small area where Urie could be best seen and understood, so Urie had taped boundaries on the floor. “It looks like you’re covering a lot of dance space on camera,” says Spahn, “even though to the performer, it looks like you’re trapped.” Even a single trip to the back of the stage made it seem as though Urie was able to range very far indeed. Every time they redid their setup, they had to get the phones back intp position and reframe the shot, and this very slightly lessened the hassle. Urie also used painter’s tape to make marks on the walls for his eyeline — this gave him somewhere to look during dialogue scenes. In Buyer & Cellar, he often switches between characters as they speak to each other, and knowing exactly where his eyes would go gave those scenes specificity and thrust.

Even if you’re recording, do it live. The particular magic of Buyer & Cellar is that it feels risky. It’s not quite theater, no, but nor is it television. Cory was a nervous wreck up till the last minute, but “having a mission like raising funds for the theater community at large meant we couldn’t stop,” he says. “We had to put our feelings to the side and work towards getting this thing done. And yes, a deadline helped.” This seat-of-their-pants quality means you can sense the broadcast’s liveness, even if you’re watching it on YouTube the next day. Spahn says they thought briefly about prerecording it, but they chose to do it live instead — he himself is a playwright with shows in the digital realm, and he knows well that a live audience is an engaged one.

“I was thinking about actors on TV and film,” says Urie. “There, you’re just a cog. But in the theater, when the show starts, it takes everything you use—your brain, your body, your voice, your emotions—the whole time until it’s over. When you film your TV show, you’re eating craft services … sometimes your costar isn’t even there. Much later it gets put together in the edit. But the exciting thing we learned with Buyer & Cellar is that live, it can feel like theater—it’s all in; it’s full out. And being able to completely go there and be full out—oh, that was like medicine for me.”