There are two short passages in Woody Allen’s autobiography Apropos of Nothing that will forever change the way I think about him. I cannot unread, unhear, unknow them. I wish I could. I’ll get to them shortly.

First, though, I want to explain that I took the assignment to read this book because I wanted to know how Allen made his movies and what he thinks about them. I realize that sounds about as credible as “I only go to PornHub for the user comments,” but let me explain. I already knew, or thought I did, what Allen has to say about the two events that have defined how he is now perceived, the first the circumstances under which his longtime girlfriend Mia Farrow’s daughter Soon-Yi Previn, became his lover, the second the accusation that he molested his then-7-year-old daughter Dylan Farrow. They are the scandals that, before rehashing them for dozens upon dozens of pages, he claims with eyelash-batting coyness that he hopes aren’t the reason you’re reading this book. (P.S. I’m pretty sure you’re not reading this book.) He has responded to both exhaustively in the past; in this book, he continues to do so, exhaustingly and finally, exhaustedly.

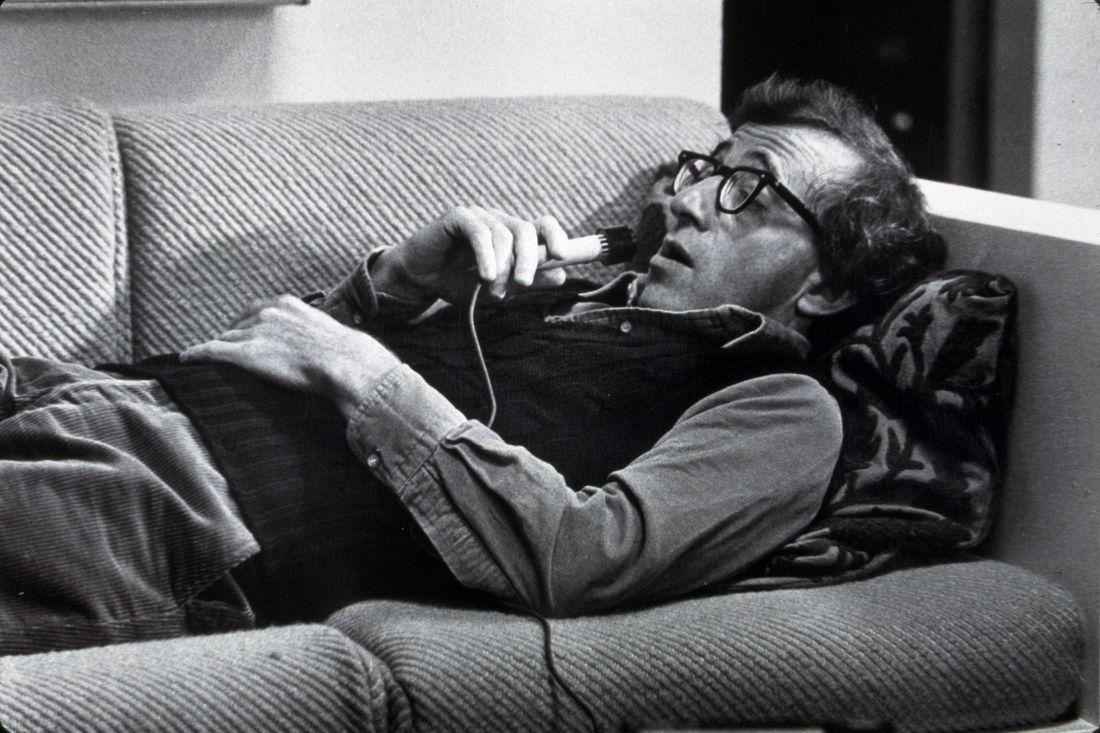

What Woody Allen, at 84, thinks of himself is reasonably clear (a more apt phrase might be “unnervingly simple”). But what he thinks about the movies he has spent the last half-century directing is not. There may be no American filmmaker alive other than Terrence Malick who has volunteered less insight into his art — his writing process, his taste in actors, his creative struggles, when he thinks he succeeded or failed, why he made the choices he made, what, if anything — please, anything! — he felt ambivalent about. He abhors and forbids DVD commentary tracks, and in the only interview I conducted with him, in 2009, alongside his still-faithful friend Larry David for a New York piece on the occasion of a movie you don’t remember called Whatever Works (with David playing the “Woody role”), I remember being struck by two things: his insistence that his actors “are free to change any of the dialogue they want” and his statement that he never watches his movies after completing them, a policy he did not alter for this volume. It is hard, in retrospect, not to infer utter indifference or complete effortlessness — the wrong kind of effortlessness. (“I just can’t get interested enough in a movie to shoot long days,” he writes.)

I understand those moviegoers who have no desire ever to watch or rewatch another Woody Allen movie. But as a film historian, I can’t remove his films from my cultural vista, because they’re not only his. Annie Hall is also an essential part of Diane Keaton’s filmography, and of Gordon Willis’s, and of Colleen Dewhurst’s, and of Jewish filmmaking, and of New York romantic comedy. And that aside, I admit I wondered whether his own take on his work might in turn shed some light on other things — the issues that, mercy me, I hope aren’t the reasons you’re reading this article.

It doesn’t happen. Yes, Allen says something (defining “something” as at least one bored sentence) about almost every one of his pictures, even the ones you’ve long forgotten existed. (What was Irrational Man? Melinda and Melinda? Hollywood Ending?) But there is little that you couldn’t pick up from an IMDB trivia page. His account of the shooting of Annie Hall begins with, “The first scene we ever shot … was the lobster scene” and ends with “I had a half-dozen different endings, eventually ending up with what you see.” Between those two sentences, he offers 91 words that nobody would call revelatory. Love & Death, he says, was “the funniest of my early funny ones” (yes, he calls them that, too), and also the movie after which, with 45 films still to go, he stopped reading reviews. On Interiors, he writes that after Geraldine Page and Maureen Stapleton came over to his apartment to rehearse and got drunk, he decided he would never rehearse any movie again, which seems extreme, not to mention deleterious to the results more than once. But Allen is not, he makes clear, big on second thoughts. He likes Husbands and Wives, the movie during production of which the Soon-Yi scandal exploded. “Mia did not exactly relish the thought of working with me … yet we completed the shooting … both being very professional,” he says. “Whether I’d still be as high on it as I was then, I don’t know. And I don’t want to find out.” You don’t? I do.

What seems to be at work here is not discretion (a word nobody on earth will apply to Apropos of Nothing) but incuriosity. “For better or worse,” he writes, “I sort of live in a bubble. I gave up reading about myself decades ago and have no interest in other people’s appraisal or analysis of my work.” Fair enough — many artists feel they need to insulate themselves that way, but Allen seems to have worked just as hard to insulate himself from … everything. He is not crazy about actors except as temporary employees; during casting, he writes, “I do not enjoy meeting people. I can never get the actor out fast enough … I have nothing to say to any of them.” Speaking of actors, there is also this: “I’ve taken some criticism over the years that I didn’t use African-Americans in my movies. And while affirmative action can be a fine solution in many instances, it does not work when it comes to casting.” Will it shock you to hear that the words “I marched in Washington with Martin Luther King” follow quickly? This appalling and antediluvian perspective is not just a blind spot or an age spot; it reeks of an iron-willed determination to resist time, counterargument, and any self-interrogation whatsoever.

I wondered if the man who has, incredibly, directed more actresses to Oscar nominations than any living filmmaker would have anything to say about how that happened. He does not. Of Husbands and Wives nominee Judy Davis, with whom he has worked five times, he writes, “I was always intimidated by her … I never spoke to her, and she, instinctively sensing I had nothing of value to say, never spoke to me.” And his cultural horizons are, he says bluntly, limited. Allen writes about music like someone who enjoys music and baseball like someone who loves baseball, but he writes about movies like someone who has been ordered to have opinions about them. Chaplin was “funnier” than Keaton, he declares. Spencer Tracy was a good actor, but not in Pat and Mike. Katharine Hepburn cried too much but was good in Long Day’s Journey Into Night. He lists films he dislikes — It’s a Wonderful Life, Some Like It Hot, Vertigo, To Be or Not to Be, sort of the flip side of the “things that make life worth living” roster of favorites he announced in Manhattan. But he expresses no reasons for those aversions and concludes, “Who cares what I think — it’s taste.” Forget caring; based on those unelaborated statements, who knows what he thinks?

In fact, the list of what Allen is not interested in could and does fill a book and includes, first and foremost, himself. We know this because he misses no opportunity to tell us. “I try never to look back,” he says. “I don’t like living in the past.” Elsewhere, he warns of “self-obsession, that treacherous time-waster.” These are possibly not the Post-Its an aspiring autobiographer should stick above his MacBook, nor would I suggest that young filmmakers take the central advice Allen offers them: “Don’t look up … Don’t be outer directed.”

So forget the movies — he certainly has. What remains is the man, and on that score, Apropos of Nothing is one of the most unsettling accounts of a life I ever hope never to encounter again, a slick comedy routine that evolves into a wildly protracted self-justification, then into the longest, most seething deposition/prosecutorial brief in history, only to finish as a series of generic toasts and hat tips. From its first pages, what is meant to amuse is as discomforting as steel-wool underwear. Allen’s riff on his upbringing feels like it could have been polished in front of a microphone 60 years ago as Mrs. Maisel took approving notes, but hoo-boy, what lurks just below the surface! He expresses bemused affection for his father but says that not “a worry nor a care ever disturbed his sleep. Nor a single thought his waking hours.” That’s supposed to read as a rimshot, but it feels more like the sharp end of a drum stick aimed straight at the eye. As for the women with whom he grew up: His mother was “not physically prepossessing” and “looked like Groucho Marx,” each of his aunts was “homelier than the next,” and his grandmother, “fat and deaf, just sitting by the window all day,” would “have been more at home on a lily pad.” His revulsion at women he finds unattractive does not come as a shock, but how obsessively he talks about it does.

So it’s unsurprising that when Allen embarks on his long history of romance, marriage, and lust, it’s all about the looks. The relatively vivid and lucid account of his early adult life as a gag writer and emerging comedian is the only part of this book that could be called introspective. Of his first, infrequently discussed marriage to a woman named Harlene Rosen (she was 16 or 17 — he writes 17 in the book — and he was 20), he writes, “Harlene’s parents never should have let their daughter marry me. True, I was showing promise in my field, but … I was an obnoxious swine.” Rosen remains a blurry figure in a vague account of a failed starter marriage — “I got on her nerves with my constant, sullen unhappiness,” he writes — but then, zing! “I knew I was in trouble when, in one philosophical discussion, Harlene proved I didn’t exist.”

That line could have come straight from one of Allen’s “early, funny” movies or from his first book of short, whimsical pieces, published in 1971 and titled, as this one surely should have been, Getting Even. It turns a six-year marriage into a setup for a punchline; the problem is, it’s not a punchline to the marriage we’ve just read about. Because mostly, Allen portrays Rosen not as a contentious intellectual castrater but as an attractive speedbump on his way to his second marriage. “She was Louise Lasser,” he writes. “The Ls in her name were formed with the tongue, which was immediately sexual.” Gross, but please continue. He calls Lasser a “knockout,” explains that she resembled “the very young, remarkably beautiful Mia Farrow,” and says other men thought she looked like Brigitte Bardot. He also calls her “my blond lady of the sonnets,” which is a lot. In Apropos of Nothing, the women Allen writes about are always initially credentialed by their looks (except for the ugly ones who raised him). But Allen then asserts that Lasser, with whom he says he is “friends for life,” was nuts, and goes on and on about how impossible her neuroses made her to live with. You are right in suspecting that you have not heard the last of this theme: Crazy women are apparently a thing that just kept happening to him.

Allen marches through his early film career in detail — you will learn more about his screenwriting work on the Warren Beatty film What’s New, Pussycat? than about 90 percent of the movies he directed — but his interest flags fast, and by the time he gets to the night in early 1978 that Annie Hall won Academy Awards for Best Picture, Director, Original Screenplay, and Actress for Diane Keaton (“my North Star”), he’s out of gas. Allen famously skipped the Oscars to play clarinet at a local New York club, as he did regularly for decades. It’s here that the first of the two passages that froze me arrives. When Allen picked up the Times the next morning and saw the results of the Oscars, he writes, “I reacted like I reacted to the news of JFK’s assassination. I thought about it for a minute, then finished my bowl of Cheerios, went to my typewriter, and got to work.”

Holy shit. It is fine not to care about awards; it is even fine to profess not to care while referencing them as frequently as this book does. But that phrasing, for the rest of Apropos of Nothing, felt like a splinter in my skull. It is a sentence that I am absolutely, unambivalently certain is true — about 1978, but much more, about 1963, right down to that whole minute wasted in thought about what for many Americans of Allen’s generation was a defining event while those Cheerios got soggy in the bowl. For me, it goes straight under the heading When someone tells you who they are, believe them.

Okay, you’ve been patient, and I’ve been avoidant. I have dreaded writing about the collapse of Allen’s decade-plus relationship to Mia Farrow (although he takes pains to present himself as merely the guy who lived across Central Park from her and her distracting brood) after she found the nude Polaroids of Soon-Yi that he had left on his mantel like, he says, a “klutz” (not the word I would choose), because, as many of you do, I found his behavior staggeringly repellent and wrong, a feeling that none of his explanations has altered, and what more is there to say about it? If you’re Woody Allen, apparently a lot, although for him, it adds up to “What’s the big deal?” In a 2001 interview for Time magazine, he remarked, “I didn’t find any moral dilemmas whatsoever … it wasn’t so complex … the heart wants what it wants.” In other words, lah-dee-dah, lah-dee-dah, la, la. Here, he says it again, at hundreds of times the length and in epic detail, much of which is devoted to an extended evisceration of Farrow as a mother and a human being. He thought he was involved with “a beautiful movie star who could not have been nicer, sweeter, more attentive to my needs … should I have seen any red flags?” “Red flags” is a phrase he returns to more than once; the only lapse of judgment he ever ponders is his failure to see how terribly she would treat him. The Farrow of this book is a monstrous avatar of fury, manipulation, and vengeance that inexplicably inflicts itself upon him. He amends that take only once, to concede that her “shock, her dismay, her rage, everything” when she saw those photos was, wait for it, “the correct reaction.” Perhaps that’s worth lingering on?

No, because he still has to get to the molestation accusation. He does; I don’t. Dwight Garner, who artfully tweezed this book for the New York Times, wrote that he believes that “the less you’ve read about this case, the easier it is to render judgment on it.” I have little to add to that except how deeply I wish I had read less. At great length, and quoting accounts and reports that corroborate his own, Allen reasserts his belief that the accusation was essentially implanted in Dylan Farrow by her livid mother and declares his innocence, saying at one point that there are people who believe he would molest a child but there are also people who believe Obama isn’t American so, shrug, whaddayagonnado? But he is at least as interested in declaring Mia Farrow’s guilt, which brings me to the second passage that stopped me in my tracks: “She didn’t like raising the kids and didn’t really look after them,” he writes. “It is no wonder that two adopted children would be suicides. A third would contemplate it, and one lovely daughter who struggled with being HIV-positive into her thirties was left by Mia to die alone of AIDS in a hospital on Christmas morning.”

I will not speculate on the accuracy of an account of the tragic end of three lives that are granted, collectively, two sentences. (There are conflicting accounts.) But what I can comment on, because it’s sitting right there, is the prose. This is writing about coldness so coldly that you can’t tell what’s giving you chills, the content or the tone, the cruelty alleged or the casualness with which three deaths are enlisted to allege it. It is brain-breaking, and the most coherent thought I could muster about it was What kind of person talks this way?

I read the rest of Apropos of Nothing in a numb daze, which is how it appears to have been written. I do not know what to make of the fact that after his no-stone-unthrown account of “all of these people running helter-skelter to help a nutsy woman carry out a vengeful plan” (an experience that “I must say was very amusing”), he jumps backward to amiably recap the movies he and Farrow made between 1983 and 1992, writing things like “Purple Rose of Cairo … coming off [Broadway] Danny Rose gives you a good idea of Mia’s range and she got better picture after picture … Mia’s range was very flexible.” (If you’re confused, by “Mia” he means the woman he just accused of causing her children to kill themselves.) This abrupt pivot to bland reminiscence puts the “mental” in “compartmentalization” and also suggests that its writing took place in a series of wildly differing moods without much attention to continuity.

That is, if it was written at all; the way he discusses actors in his more recent movies strongly implies the prodding of an unseen interviewer (or editor) with the patience of Job, saying, “Any good Owen Wilson stories? When I mention Rachel McAdams, what comes to mind? Tell me your impression of Joaquin Phoenix.” Prepare yourselves for some hot dish: Wilson “was wonderful and a pleasure to direct,” McAdams “makes every line real and looks like a million bucks from any angle,” and as for Phoenix, “all you have to do is check out his movies over the years to know he’s an amazing actor.” That, and the way Apropos of Nothing is dotted with “Anyway, where was I?” and “To get back to the point” and “Sidebar” suggests dictation more than writing. (Speaking of which, sidebar: Among the targets of Allen’s wrath is New York, which he says bowed to pressure from Ronan Farrow to soften material hostile to Mia Farrow in Daphne Merkin’s largely sympathetic 2018 account of his life with Soon-Yi Previn.)

Eventually, after a swipe at “#MeToo zealots” and some stats about how many women he has employed, Allen announces that he is “forced to return to the tedious subject of the false accusation. Not my fault, people. Who knew she was so vindictive?” By then, even the most diehard reader may be done with this 392-page attempt at a testimonial legacy by someone who has long insisted that he does not care how he is thought of after he dies — or, it seems, before. “To me,” he says, “the best parts about proofreading the galleys were my romantic adventures and writing about all the wonderful women I was passionately smitten with … For students of cinema, I have nothing of value to offer.” He also quotes Francine du Plessix Gray as having said, “There are no great Woody Allen stories.” On this, henceforth, I will take him at his word.