I first heard about Josh Oppenheimer on my initial Harvard visit, the spring of my senior year in high school after I got accepted. Josh would go on to be a well-known documentary filmmaker, but back then, my host described him as this brilliant queer performance artist who lived in his entryway and was doing a show the following night in a drained swimming pool. When he invited me to come along, I was too intrigued to resist.

But once I found myself crowded around the far end of the pool at Adams House, I couldn’t really follow what the piece was about. I only witnessed the teetering danger of Josh potentially falling into the pool as he pontificated at the edge, bald-headed in a white minimalist tube of a gown that made him both androgynous and alien. His pronouncements had an air of importance, the youthful conviction that his words had never been said before. Even the moments when he had to get into the pool using the rungs of a ladder, an awkward maneuver at best, were imbued with a certain delicacy of purpose, lit as he was by those clip lights you get at the hardware store. As he declaimed, and asserted, and pronounced, in ways that resisted my attempts to comprehend, I did understand that if this was something I could do at Harvard — witness and celebrate the illegible yet ardent manifesto of a gowned man in a drained swimming pool — then maybe I could blend right in.

But instead of following Josh’s focused example, I’d spent so much of my time at school craving boys, too many hours cruising for them on‑ and offline. I heard of a kiss-in he and some friends were planning for Ralph Reed, the head of the Christian Coalition, who was coming to Harvard that fall; I decided to join.

Josh explained the details of the action at a meeting, though the logic remained unclear to me. We were to dress conservatively and pretend to be homophobes by holding up signs borrowed from Fred Phelps and the Westboro Baptist Church, like GOD HATES FAGS and NO RIGHTS FOR SODOMITES. The signs were meant to expose Ralph Reed’s hypocrisy and Harvard’s disingenuousness for inviting him. Though Reed seemed benign and respectable, he still reeked of the same homophobia as Phelps and his cronies. This logic made sense in a somersaulting kind of way, though I still wondered why we couldn’t just kiss as we were and send a less confusing message.

Though I got on board in the end and put on the black wool suit I wore to interviews, procured at Filene’s Basement with extra money from the Winter Coat Fund, which gave every Harvard freshman from west of the Mississippi $300 to buy warm clothes. The suit was an armor I didn’t want, that cover of respectability and dominance as a man. I couldn’t handle the idea of wearing a tie, so I settled for a linen shirt with a mandarin collar, unclassic but respectable.

I got to the auditorium early and made my way to the queer section in the center near the back. The group wasn’t big, maybe twenty kids or so. I was chatting with one of them when Josh appeared in the periphery of my vision wearing a white dress, and I hadn’t quite absorbed his outfit before he asked, “Would you be my kiss-in partner?”

That was when I noticed he was not only wearing white but that his head was covered in a wimple, and I recognized the familiar crisp fabric of a nun’s habit from my dozen years in Catholic school. I had no idea why he asked me, the two of us having never hung out as friends over four years, but I nodded yes. Maybe it was as simple as me having the right look, a studious blond man in conservative clothes. I sat next to him as Ralph Reed’s talk began, though there were still murmurs among us about who was ready to take action and who wasn’t, who was risking arrest and negative backlash, or some sort of permanent smirch on some record, official or otherwise.

I had my doubts as Reed started his speech. I still wasn’t quite getting the point of all the theatricality, as I held a sign that read DYKES WILL BURN IN HELL. Was this all a manifestation of Josh’s ego? Judging by the absence of the more mainstream queers among us, the gay guys with their tight shirts and muscles, there didn’t seem to be full consensus that this was a good idea.

Yet I also didn’t have much to lose. I was already queer, albino, poor. I had no reputation to protect, no parental expectation to live up to. Something told me it was worth the risk, that whatever it was on the other side of Josh’s parted lips would have meaning.

We stood up to begin the kiss-in at the start of the Q&A. I felt Josh tug at my jacket, a gesture that betrayed our lack of intimacy even as we were about to perform an intimate act in public. There was something unremittingly attractive in Josh’s subversion, something that drew me to his face surrounded by cloth, the memory of my years among the nuns. So that by the time Josh’s forehead nearly brushed the rims of my glasses as his lips touched mine, I felt ready.

Am I kissing a man? That was a question I found myself asking in the ensuing confusion like drowning, as my fear merged with the audience’s agitation. Am I even a man? I had never kissed a girl before, and Josh was the closest by far. But the feeling of plugged ears under the sea prevented me from quite understanding what was happening, punctuated by moments when my consciousness bobbed for air even when my lips didn’t catch a breath.

In one of those moments of clarity, Josh’s kiss shook me into the awareness that I was not quite a man. I wanted to be in his nun’s habit and not my suit, because a dress to me meant a release from the shackles of forced masculinity, a giving up that I felt somewhere between and within my heart, my gut, and my groin. It took Josh’s kiss for me to admit to myself that I desired to be taken, not that only men take and women receive but that I could never be just a taker and never be just a taker as a man. I tensed then, gripped his lips with the confident force of learning who I was between tongues.

Even when the guards tried to break us apart, our tensed arms held on to each other. Our legs splayed as those guards pulled our feet from under us, and still we didn’t let go. Those guards had to carry us out of the room, entwined and horizontal. Finally, as I lay on top of him on the pavement outside, Josh opened his oracular eyes and we broke apart. By then, I knew that my fascination with women, from their art to their plight, wasn’t just a part of me I could parcel off, but that womanhood itself might be the vessel that best contained my being.

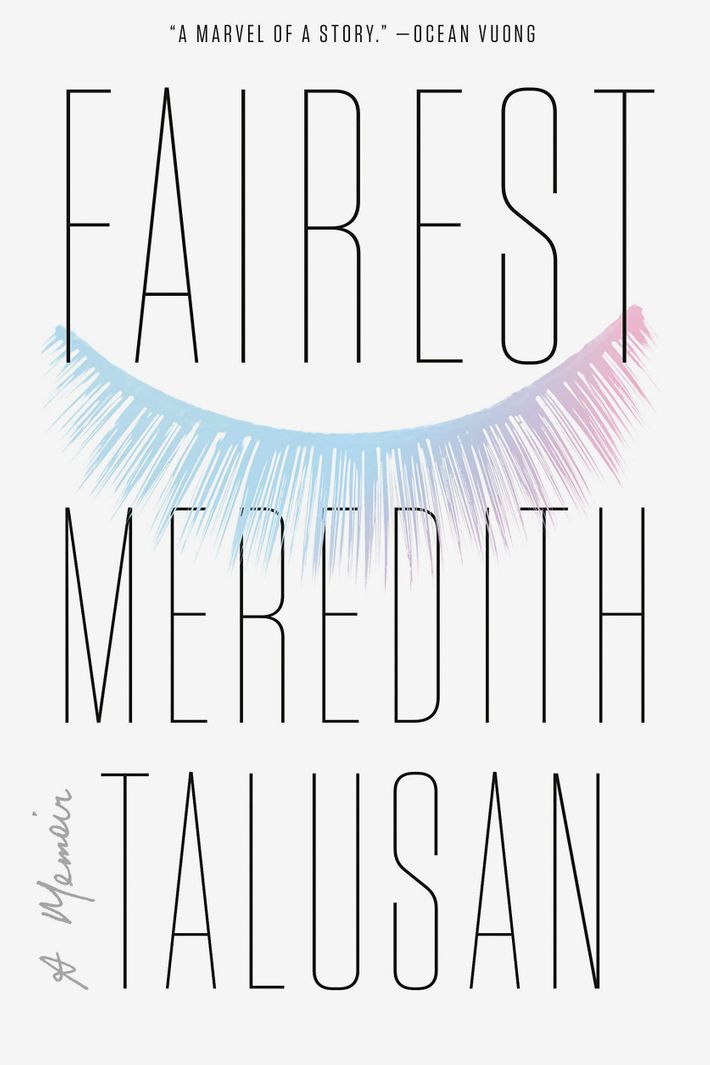

Fairest, a debut memoir by Meredith Talusan, to be published on Mary 26, 2020 by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Meredith Talusan.