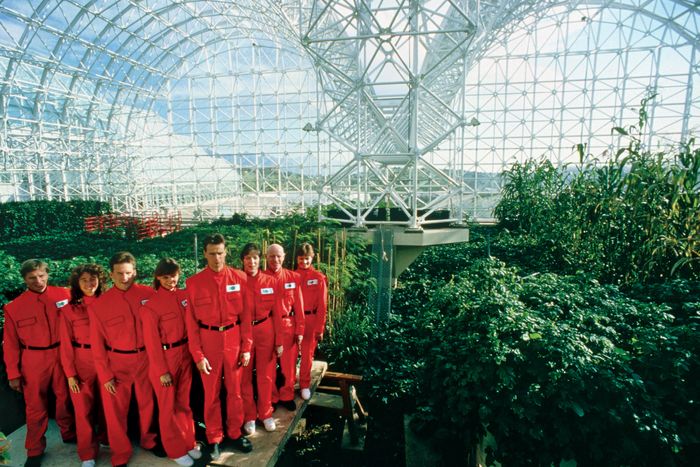

Tainted in the public imagination by misfortune, miscalculation, and lack of transparency, the 1991 experiment in sustainable living known as Biosphere 2 went from being viewed as the coolest thing ever, to a scam perpetrated by a New Age cult, to — most ignominiously — the basis of a Pauly Shore comedy, Bio-Dome. Matt Wolf’s sympathetic, intermittently cringe-inducing but very entertaining documentary Spaceship Earth sets out not so much to correct the record as to liberate Biosphere 2’s architects and participants from their fate as a punch line. Yes, this hermetically sealed three-acre terrarium for eight humans and an ark-load of animals and plants in the Arizona desert had its off days, and the personalities inside that formidable glass structure and in the nearby mission control were a tad eccentric. Maybe more than a tad. But the science wasn’t as inexact as all that. And viewed as a sort of epic Happening, an expression of the healthiest, most adventurous aspects of the counterculture as well as the fervent desire to protect the planet, the Biosphere 2 that emerges from Wolf’s documentary merits respect, even awe. It’s a shrine to the kind of utopian idealism that has been laughed out of civilization to our detriment. You think not? Consider what has replaced it.

Those eight people do look rather silly in their astronaut suits, trudging into the mammoth glass enclosure while onlookers cheer. But then Wolf whisks us back 25 years to Biosphere 2’s seeds — organic ones, you could say. Kathelin Gray recounts meeting charismatic engineer John Allen in San Francisco in the ’60s while she was reading René Daumal’s in-search-of-the-self allegory, Mount Analogue — serendipity at its dippiest. They and a group of other self-searchers formed a commune that became a traveling theater troupe (Theater of All Possibilities) and, when the SF scene began to strike them as overly commercialized, relocated to a New Mexico ranch dedicated to the principle of synergy. They called said ranch Synergia. Maybe you’re rolling your eyes, but this stuff floats my boat. It floated their boat, too. They designed and built one big enough to sail the world and called it the Heraclitus, after the man who left a privileged life to argue for a harmony of opposites. Some Synergists probably came from privilege as well, and Allen was skillful enough to seize the imagination of the billionaire oil heir Ed Bass, whose money built a Kathmandu hotel and eventually Biosphere 2. What a life: days of farming, playmaking, and geodesic-dome building and nights of reading from Buckminster Fuller while paging through the Whole Earth Catalog. They read William Burroughs and then Burroughs came and read to them.

Some Synergists talk to Wolf with a mixture of bitterness and longing, a tone you hear often from people who believed in the counterculture’s fruitful ethos rather than its druggie animism. The Synergists didn’t want to be stardust and golden and go back to the garden. They wanted to design and plant the garden and figure out how to make it flourish without poisoning the Earth or sucking it dry. And so there was Biosphere 2 — so named because Earth itself was Biosphere 1.

Television talking heads were everywhere in the heady days preceding the sealing of Biosphere 2, and there’s no shortage of film shot on the inside by people hoping to show the way forward. Wolf gives us cheerful montages of sowing and reaping in multiple habitats — a rain forest, a desert, a coral reef. There’s even a homemade music video. But then the denizens of Biosphere 2 begin to get testy.

What went wrong? Wolf’s subjects note several kinks in the system. One is Roy Walford, a doctor who believes they can live well into their 100s by starving themselves half to death. They all survived the interlude, but their expressions are those of prisoners, while Walford — showing off his lean body mass and sinews — seems an out-and-out nut. Agricultural manager Jane Poynter loses the top of her finger in a thresher and needs to return to Biosphere 1 to save the rest of her; but when she comes back, it’s with a suspicious extra piece of luggage — a no-no. (The deal is that nothing comes in and nothing goes out.) The media and resentful scientists label the group a cult, with talking heads bringing up its habit of donning costumes—which would seem de rigueur for a theater troupe, but nobody mentions that part. Spaceship Earth builds to a lesson on what happens when CO₂ starts to take the place of oxygen. Group dynamics and plants shrivel. People get mean. CEO Margaret Augustine clams up about what’s happening, and under increasing scrutiny Allen seems to unravel. Bass brings in scientific advisers with axes to grind. (They’re dismayed that a theater collective got the money that was their due.) Later, he also brings in Steve Bannon, fresh from Goldman Sachs. Seeing the young Bannon sickens you, like too much CO₂.

The movie packs a lot in but still leaves gaps. Time stamps would have been nice, since we have no idea from scene to scene how many days have elapsed. Central questions go unanswered. I’m no environmental scientist, but I’d have liked to know why Biosphere 2’s designers didn’t reckon with rising CO₂ levels. I’m no gossipmonger, either, but I’d have liked to know who was busting whose chops and being a pain in the ass. Pauly Shore went there. Wolf could have, too.

But we meet some marvelous characters, among them Linda Leigh, who describes herself as the kid who could always be relied upon to feed the animals in her schoolrooms. She has reconciled herself to nerdy isolation but not to disruptive neuroses and cover-ups. People like Marie Harding (who married Allen, though evidently not for love), Mark Nelson, and riven whistle-blower Tony Burgess speak to Wolf with lingering emotion. They want us to know that in a successful experiment, you learn as much from what fails as what succeeds.

I went into Spaceship Earth — let me revise that … I clicked PLAY on the link thinking that I was going to see a black comedy on the order of those Fyre Festival documentaries. Instead, I was reminded of everything I’d been missing in a culture that ridicules “crunchiness” more than amoral consumption and greed. Viewed under quarantine, Spaceship Earth has a visceral kick. What if isolation, what if cherishing every square of toilet paper, leads to a heightened awareness of how heavily we’ve lived on the Earth? What if it forces us to realize that Biosphere 2 was an unnerving distillation of life on Biosphere 1?

*A version of this article appears in the May 11, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!