There have not been many winners in the fight against the coronavirus, but Michael Jordan treated it like the LaBradford Smith of infectious diseases, another in an endless series of perceived slights to motivate a legendary performance. The Last Dance was going to be a documentary event under any circumstances — insofar as a documentary could be considered an event — but in the absence of live sports, save for Korean baseball and masked cornhole-ing, it became a weekly obsession. It nourished starving sports pages and basketball podcasts. It colonized trending topics on Twitter every Sunday, producing an endless wellspring of clips, memes, and quips about Jordan’s on-court exploits and on-camera braggadocio. It became the type of watercooler event that the splintering of viewers across various networks and streaming services has made virtually impossible for years.

It felt like the greatest sports documentary ever produced. It is also, in the cold light of day, a flawed and dubiously motivated documentary. That’s the cognitive dissonance of life under quarantine: When you’re this hungry for entertainment, everything tastes like filet mignon. (See also: King, Tiger.)

The highlights of The Last Dance are too numerous to mention, as befitting a ten-hour tribute to a player and pop-culture figure of Jordan’s transcendent stature. And with full credit to the director, Jason Hehir, some of those highlights were unique to the documentary, sparked by the great collective storytelling of Jordan’s teammates and other witnesses, and by Jordan himself, whose tongue was perhaps loosened by tumblers of $1,600-a-bottle tequila. The length wasn’t a problem either: There are enough juicy subplots here to supply spinoff documentaries from now until the time 8 billion doses of the coronavirus vaccine are distributed.

Yet the soul of the documentary was more difficult to locate. Each episode drew us deeper into Jordan’s pathology — not as a means to comment on it but as another tool of his dominance. Consider Justin Timberlake’s blink-or-you’ll-miss-it appearance talking about shoes in the stretch about the Nike deal that changed the face of the industry. While there’s an argument to be made about Timberlake’s relationship to the Air Jordans — a special beige Air Jordan III figured into a track on his album Man of the Woods — the real point of his appearance is to bring an arena-filling pop star to heel. Ditto Barack Obama, “former Chicago resident.” They’re not adding substance so much as buttressing a monument.

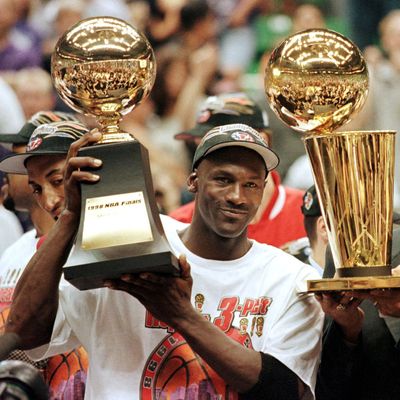

The context for The Last Dance is the amnesia that naturally comes from the passing of the torch from one generational superstar to another. Young NBA fans know LeBron James as the best ever, and it’s their parents who keep insisting they’re wrong. The ever-mercurial Jordan had been reticent to make the case for himself, perhaps because he’d have to account for the less noble aspects of his personality and career, but the documentary is geared toward that purpose first and foremost. It seems no coincidence that Jordan reportedly agreed to participate as LeBron was bringing a championship to Cleveland, perhaps his greatest single accomplishment on the court. The doc may be premised on an abundance of original footage of Jordan’s final championship run with the Chicago Bulls, with that core unit of Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Dennis Rodman, and coach Phil Jackson. But it’s a comprehensive argument for Jordan’s greatness, timed to undercut the twilight of LeBron’s own run, which still has him playing MVP-caliber ball in his 17th season.

That being said, it’s a persuasive argument, backed by footage and testimony that poses Jordan as a rare combination of athleticism and indomitable grit. Some of the complaints about the documentary revolved around the structure, which cuts between the ’98 season and a converging timeline that covers the rest of his time in the league. Hehir loosely arranged the earlier timeline around key players and chapters — there are episodes half-focused on Pippen and Rodman, and the Dream Team and his stint in Minor League Baseball — but he gave himself the latitude to pivot away from them when necessary. And there’s an elegant, associative quality to how moments from the ’98 season connect to some memory in the past, like history repeating itself. (It helps that Jordan’s grievance-based approach to competition links to every triumph in his career. As fuel to this engine, Jerry Krause should have a statue outside Chicago’s United Center, too.)

But The Last Dance was not O.J.: Made in America, the multipart ESPN documentary that became an early point of comparison. The comparison may seem unfair, given that Made in America was not at all interested in lionizing an all-time-great athlete, but it is fair to expect a documentary of this length and scope to be more substantive than a highlight reel. From the start, Made in America was always bigger than O.J. Simpson, whose life before and after the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman was explored in exceptional detail but who was considered more a flash point for a larger discussion about race in America. As entertaining as The Last Dance was, every episode made it narrower and insubstantial, smothered by the ego of an athlete who controls his brand as forcefully as he once manipulated teammates or shut down rivals on the defensive end. Hehir may get the credit, but Jordan is a Pippen-level creative facilitator.

The in-house qualities of The Last Dance are most apparent in the yadda-yadda treatment of Jordan’s missteps: his alleged gambling addiction and his involvement with unsavory characters like “Slim” Bouler, his refusal to give public support to Harvey Gantt’s challenge to racist senator Jesse Helms, his abusive treatment of teammates, and other moments when fans might not want to “Be Like Mike.” In the lead-up to the broadcast, Jordan set expectations ingeniously by predicting that some viewers will think he’s a “horrible guy” after seeing The Last Dance, but that wasn’t the case at all. This prediction gave cover to a hagiography: If people are under the impression it’s a warts-and-all documentary, then they missed the fresh layer of polish applied to the bronze.

And yet The Last Dance was revealing of Jordan’s character all the same. His need to assert his dominance, even now — by scoffing at Gary “the Glove” Payton’s defensive prowess in the Bulls-SuperSonics series or beefing with the Detroit Pistons three decades later — speaks to a pathology that won championships and MVPs and condemned him to solitary confinement. The documentary had the intended effect of boosting Jordan’s standing as the greatest ever — the footage is dazzling in any era, and his passion and will is a phenomenon in itself — but there’s a hollowness at its center that’s surely accidental. Like Jordan’s infamous Hall of Fame induction speech, The Last Dance celebrated a win-at-all-costs mentality that inspired awe and pity in equal measure. When the endorphin rush is over, you’d rather not be like Mike.