It’s the new American pastime: You’re up past midnight, scrolling through Wikipedia, caught in a vortex of esoterica. The average procrastinating person sees this as a great way to kill a few hours, but for documentarian Matt Wolf, it’s how he finds work.

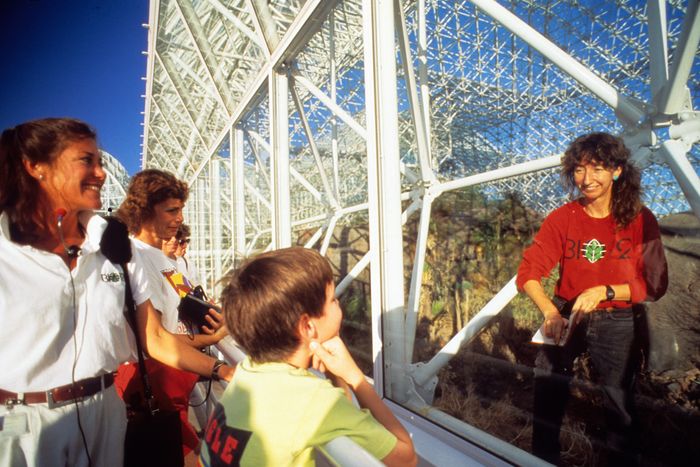

“I was doing research on the internet, as one does to find film ideas, and I came across these striking images of eight people in bright red jumpsuits,” Wolf tells Vulture over the phone from his home quarantine. “They were looking almost like the band Devo, except they were in front of an enormous glass pyramid. I assumed they were from a science-fiction film, but it didn’t take me long to learn that this structure was in fact real.”

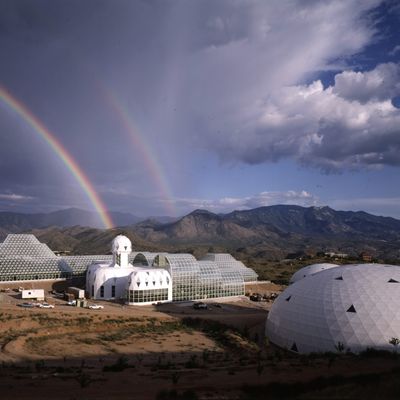

The Devo tribute band was actually a group called the Biospherians, so named for their notable temporary residence in the mighty, gleaming Biosphere 2. (Biosphere 1 is Earth, of course.) The eight-person crew sealed themselves in a self-sustaining geodesic dome located outside Tucson, Arizona, for a staggering two-year period from 1991 to 1993. Their goal? To create a closed system capable of fostering life on a long-term scale. Their project could have been the first step toward realizing the fantasy of an outer-space colony or, at the very least, a gold mine of fresh data shaking up scientific inquiry. However, a media firestorm, oxygen filtration issues, bug infestations, and the frailty of the human ego managed to complicate matters.

That’s the strange-but-true story behind Wolf’s new film Spaceship Earth. Balancing trenchant reporting with oddball entertainment, he tracks the Biosphere 2 from its origins as the utopian brainchild of free thinkers in the post–Summer of Love era. “The project was regarded as a spectacular failure, and that’s part of why its reputation has been misunderstood,” Wolf says. “When I learned of the larger history of this group and the project, I saw the potential to tell a much bigger story, an epic story spanning half a century and grappling with big ideas about human aspirations as well as their limits.”

The Biosphere 2, Spaceship Earth’s ostensible subject, only appears about halfway through the film’s run time; to understand its significance, we must first understand the Synergists who summoned it into being. Founded in the ’60s and modeled after Buckminster Fuller’s principles of structural cooperation and harmony, the ecological conservationist-slash-entrepreneurs-slash-theatre troupers did whatever felt right and paid for itself. “We avoided being put into any box. Even ‘alternative communities,’ we found that too confining,” says Dr. Mark Nelson, an early Synergist and one of the eight original Biospherians. “I’m a product of the ’60s. I graduated from Dartmouth in ’68 and decided I didn’t want to do anything conventional. I wanted to contribute to the world, but I also wanted to live a balanced life.”

The Synergists combined philosophy with sober scientific reasoning, adopting pie-in-the-sky ambitions and then backing them up with the required expertise. They established responsibly run ranches, completed some for-hire contract work in the eco sector, sold tickets to their green-minded plays. After completing construction on a fully functional ocean-faring vessel named The Heraclitus, then their most major accomplishment, they became curious about the kind of isolation possible on the high seas. What if such research conditions could be re-created on land, on a grander scale? What if in order to contribute to the world, they needed to build a new one? With significant financial contributions from eccentric billionaire Ed Bass, Biosphere 2 became a reality.

“All my life, I’d been a person who wanted to quote-unquote ‘save the world,’ working on issues of habitat restoration,” says Dr. Linda Leigh, a Biospherian who joined the effort in the ’80s. “I was working for the Nature Conservancy, and I met one of the people from the Biosphere project, and he said, ‘Linda, you can’t save the world all by yourself.’ I got invited to meet everyone else on the team, and I saw a group united in a cause that I really loved. They invited me to come work, and I dropped what I was doing, and that was that.”

Nelson echoes her memory: “After graduating from the Ivy League, I wanted to do something that would be difficult, and I wanted to live a life that would be more satisfying than plugging into an organization and doing something anyone with my background could do. When I heard the [Biosphere 2] program was ecology, enterprise, and theater, it sounded like a balanced and fulfilling life.”

A viewer of Spaceship Earth soon realizes that this tempered idealism was the engine fueling Biosphere 2, a force too pure to last. The first of two missions began in ’91, sealing eight crew members inside a closed system comprising living quarters, a toxic-chemical-free agricultural and work space, and seven biomes — each a different ecosystem, from a rainforest to a fog desert to a savannah grassland. Tasked with studying the interactions between humans, plant and animal life, farming, and technology, the goal was to experiment, broadly speaking. But various snafus made even day-to-day living for the quarantined crew members difficult — some obstacles inconvenient (insects infesting their kitchen) and others more troubling (compromised air put undue strain on their lungs). And those snafus made for tempting headlines.

On the outside, society did not share the crew’s belief in the value of such unstructured research; without an immediately beneficial outcome in mind, it appeared to most as an expensive lark. When the media began covering the flawed endeavor and its hippieish origins in counterculture theater came to light, some went so far as to cry cult. What began as an ambitious, futuristic scientific adventure was soon cast as New Age nonsense. “I didn’t really care [about the cult accusations],” Leigh says. “People can say what they want to say. I was thoroughly entrenched in it, and it was an excellent lifestyle for me. I let it roll off my back, the whole ‘cult being a negative’ thing. What we did was extraordinary.”

From his archival vantage point, with 600 hours of footage and two thousand slides at his disposal, Wolf was able to see that extraordinary quality as well. “They had filmed an incredible volume of material from their life’s work, and we got to catalogue that collection, then mine it for insight on their vision. We were also able to use the footage Biospherian Roy Walford shot when he intended to make a documentary inside,” he says. “It’s unusual to have access to a story so byzantine in its complexity and just have every piece of it right in front of you.”

Those pieces, put together, provide an unusual history of an environmentalist movement, imperfect as it was. Mission drift, discord, and external opposition can send the most commendable efforts awry, but amid the chaos are lessons learned. “My editor David Teague and I really leaned into a concept that Mark Nelson talked about,” Wolf says. “It was about ‘small groups of people being engines of change.’ We recognize a unique model within this group that we think is instructive about realizing unprecedented ideas … This group defied the traditional clichés of hippies. They were real capitalists pursuing enterprises around the world they hoped would be both ecologically and economically sustainable. That’s the neoliberal dream. Through the course of their epic journey, you see the shortcomings of that.”

Wolf ultimately found the core of his narrative in the psychology of the isolated characters and their absolute commitment to a cause amid power struggles and the emergence of competing factions. “Despite tribulations and limitations to the scope of their ideas, the relationships between the Biospherians have sustained,” he said. “That felt profound to me.” Each of the eight voyagers into the unknown claims to have left Biosphere 2 a changed person, seeing the precious resource of nature anew. Leigh says she gets “angry when I see people stepping on plants, because they’re part of our oxygen supply.” A couple months after leaving the Biosphere, she was at her dentist’s office when she noticed that there were no plants around. “And I just lost it. ‘Where does your oxygen come from?’ I just blurted it out. He probably thought I was a nut.”

Spaceship Earth exists in no small part to capture the electric charge of such an experience, of dreams and discontent, world-changing ambitions and soul-crushing realities. It’s as much a story about regrets and what could have been as it is about accomplishments and the idea of a different kind of future — a perspective not unwelcome now, in our isolated present. “Scientific inquiry and philosophy are both about forming hypotheses, questioning ideas, and creatively solving problems,” Dr. Leigh says. “I’m proud of what we did. I’d do it again in a heartbeat.”