Every now and then an artist comes along and changes their field so completely that their fingerprints seem present in everything that comes afterward. John Carpenter’s Halloween birthed many decades of creeping, suspenseful shots of horror-movie killers stalking their prey, picking off decadent, unsupervised teenagers one by one in locations conveniently out of reach of parents and police. Jimi Hendrix’s Are You Experienced? led generations of electric-guitar players to wield their instrument like a chainsaw, cutting through blues-rock grooves with stabs of guttural noise where his predecessors staged a more mannered attack. Remembrances of Kobe Bryant in the wake of the Laker legend’s untimely passing in the winter illustrated the influence not just of Kobe on basketball, but also of Dave Chappelle on millennials. The “Love Contract” sketch from Chappelle’s Show is half the reason people yell “Kobe!” when they throw anything at a basket, on the court or off. It’s one of a dozen tics and catchphrases we’ve forgotten we take after the comedian. (The “Racial Draft” gag resurfaces nearly every time a black celebrity loses the plot, as does Rick James’s “cocaine is a helluva drug” line, for many of the same reasons.) Chappelle’s piercing clarity with regard to matters of race and his ability to illustrate the absurdity of the American experience through calculated exaggeration are his great gifts to 21st-century thought. They’ve bled into the way we think and the way we speak.

You can’t stay cutting-edge forever. Chappelle’s retreat to the Ohio plains at the height of the success of his show, and his subsequent return to stand-up a decade later, are a clinic in the ways a lacerating wit can rust and the danger of receding into the comforts of an echo chamber. Jokes about transgender women in recent specials cast the comic, once a hero of the underdog, as an Establishment figure of a sort, punching down in the ways his work used to ridicule and detest. Doubling down when criticized put him in the league of millionaire comics who don’t get that their anxiousness to fight this generation means the tables have turned.

More fascinating than their objections to a changing world is their inability to see themselves as the old guard. They’re pining for simpler times, but what made those times simple is the dearth of outlets where people could express themselves. (Those glory days were marred by fines and complaints from angry politicians and parents; veteran comics’ habit of saying the era of “family values” conservatives was a better time for free speech than the present is a lie deserving of its own essay.) The latter-day Chappelle specials are brilliant, but also distractingly fixated on people who don’t love every joke in the absence of any demonstrable blowback for critics’ objections, a problem haunting every comic who pauses a set to complain to an audience of admirers about other people who don’t admire them. It’s a funny paradox. Either you care or you don’t. You’re not unbothered if you keep checking the comments.

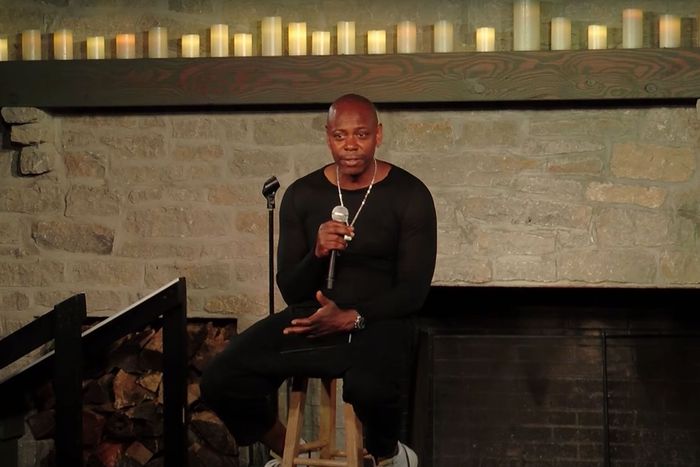

This month, Chappelle made history by releasing the first official stand-up show footage performed to a socially distanced audience since the COVID-19 crisis closed clubs across the country. 8:46 is a clip released Thursday night from Dave Chappelle & Friends: A Talk With Punchlines, an event held in Ohio a week ago on June 6. It deals with the fallout from the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis last month and the protests in 50 states and around the world demanding racial justice and government action to curb police brutality. It’s Chappelle’s most poignant material in ages. The outrage is pure and unfiltered, more like a stressed-out bar hang or a video essay using historical parallels to illustrate what is acutely agonizing about 2020 than a gig meant to draw laughs. “This isn’t funny at all,” he says at one point, overwhelmed by the heaviness of his subject matter.

What’s different this time is that he’s almost exclusively boxing upward, or at least sideways, now. The targets are police violence and cable-news personalities trying to make sense of the day’s malaise. Conservative pundit Candace Owens catches hell for kowtowing to the alt-right. (The riff about Owens spent a little too much time showering her with nonspecific locker-room jabs and not enough spelling out what’s uniquely insipid about a black media figure swooping onto a story about police violence demonizing the dead and denying race as a factor in police brutality, performing equality for the sake of appealing to the white Republican gaze.) Don Lemon gets smoke for trying to shame celebrities into speaking up. Chappelle’s defense is sound. We know where he stands. The movement doesn’t need celebrity platitudes. The unveiling of the “I Take Responsibility” campaign, where famous white actors laid it on thick about privilege, happened earlier in the day, exemplifying the cloying corn that can come from forcing rich people to take a stand.

It was almost perfect. Overnight, an eagle-eyed Twitter user noticed a discrepancy between the closed captioning and the audio and video of the 8:46 performance, which currently lives on Netflix’s comedy channel on YouTube, specifically in the section on Don Lemon. At the 7:45 mark in the audio and video, Chappelle calls the CNN host’s show a “hotbed of reality” with a laugh, takes a sip of his drink, then the camera cuts to the audience and back to him telling the story about being called out on the air for his presumed silence on Minneapolis. The clip posted to Twitter shows a riff in the closed captioning that isn’t present in the video: “Don Lemon is a funny newscaster because he’s clearly gay, but … he’s the anomaly. He’s black and gay, but unlike my other black and gay friends, he’s got this weird self-righteousness …” Then it shows Chappelle preparing to do an impression of the anchor, which tracks with the silly voice he puts on at the 7:48 mark as he begins to recount what Lemon said on the air, which would suggest that a portion of the joke was cut that stayed in the closed captioning. By morning, as the clip spread on Twitter, captioning on 8:46 was disabled. Later in the day it was restored, but the words jump ahead of Chappelle by one line right at the section in question. (Vulture reached out to Netflix and is still awaiting comment.)

What happened here? What changed in a week? Is Chappelle just incapable of going 30 minutes onstage without proclaiming that he doesn’t get what makes queer folks tick but suddenly net-savvy enough to know to filter himself now? Or did he pull those lines because he’s beginning to see the light, because it undercuts his message about the chilling consistency of black pain and disenfranchisement across centuries to single out one subdivision of black man for ridicule? Whatever the case, Chappelle in middle age still mirrors his audience. We’re coming together, and fast nowadays; we still have a ways to go.