There was a time when people, usually men, made blithe generalizations about the predictability of women’s preferences in jivey jargon: “Chicks dig this,” and “chicks dig that.” The thing is, the band that’s carried the word “chicks” around in its name since 1989 — recently lopping off the “Dixie” that appeared in front, due to the word’s historic usage as a romantic reference to the Confederate South — has proven utterly unpredictable all along. There’s no precedent for the career the Chicks have carved out — how they changed the way women carry themselves in country music, only to be expelled from that world in an ugly turn of events that emboldened them in new ways. As Natalie Maines, Martie Maguire, and Emily Strayer today release Gaslighter, their first album in nearly a decade and a half, it’s an ideal time to revisit pivotal moments along their fraught path.

Pre-fame

1989: The quartet that dubbed itself the Dixie Chicks at the close of the ’80s — a cheeky spin on Little Feat’s boogie-rocking 1973 mythology of a Memphis seductress — bore little resemblance to the group that would ultimately bring the name to fame. But already in place was an aspect of musical identity that would help set them apart in every music scene they would go on to inhabit: These were women putting their instrumental virtuosity to use. Sisters Emily Strayer and Martie Maguire, then going by their family name Erwin, were still in high school and college, respectively, when they brought chops honed through years of study, woodshedding, fiddle competitions, and bluegrass festivals to a group rounded out by fully grown pickers and co-lead singers Robin Lynn Macy, a school teacher and guitarist, and upright bassist Laura Lynch. They started busking on the street for tips, and gradually built an appreciative audience in and around their home base of Dallas, their early repertoire heartily utilizing traditional bluegrass and Western swing playing styles. After their first independent album, 1990’s Thank Heavens for Dale Evans, the Chicks opted to evolve into a slightly more modern country band, a direction that displeased Macy enough for her to leave the lineup. The remaining Chicks worked their way up to a busy tour schedule in an RV, and stuck with their throwback cowgirl stagewear.

1990s: Finding Natalie and Their Sound

1995: Sony Nashville gave the band a development deal to cut new demos, and concluded that the Chicks’ chances of making the leap to the big time would be vastly improved by replacing Lynch with a new lead singer. Enter Natalie Maines, who’d been trying the music programs at a series of colleges. Strayer and Maguire had heard the scholarship-earning Berklee College of Music audition tape she’d recorded with her dad, Lloyd Maines, a respected producer and steel guitarist in Lubbock, who raised her on country of a distinctly rocking, rootsy flavor, like the kind made by Joe Ely, whose livewire honky-tonk outfit — which included her dad — once toured with the Clash. The younger Maines had internalized distinctly country vocal techniques, how to sing hard in her head voice and apply punchy embellishment, dipping her pitch in the middle of lines and tugging notes up or down as she released them. Her personality was the real selling point; her performances felt freed-up and charismatic. She brought irrepressible sass and savvy to the group, and nixed the retro outfits.

1996-1997: The Chicks entered the Nashville system with powerful record men, Sony’s Blake Chancey and Paul Worley, as their producers, but still found themselves severely underestimated in an industry that favors its familiar molds. The perception was that a trio of spunky, stylish young women must have been the label’s attempt to capitalize on the Spice Girls craze of the time with a country-pop clone, and wasn’t an act worth taking seriously. This was still the era when country acts, especially newly signed ones, relied on songs written by proven Music Row pros. The Chicks and their producers initially had a hard time convincing Nashville publishers to give them quality material to consider for their album, until they went around doing informal showcases to clue people in about what sort of group they really were — one with a combination of string-band musicianship, spirited solidarity, and popular ambition that hadn’t been seen before.

1998: A lot of women who had stepped into the country spotlight as 20-somethings during the ’90s turned to adult-contemporary templates as a source of modern sophistication. One who was even younger, the then-teenaged LeAnn Rimes, scored her breakthrough by projecting torchy, mature taste. Shania Twain’s youthful verve and forwardness definitely stood out. Then the Chicks arrived, sounding like no one else. At a time when fiddle was fading from the format, banjo was a distant memory, and all the studio playing was left to hired session musicians anyhow, Strayer and Maguire insisted on contributing their own instrumental parts to their major-label debut, Wide Open Spaces, flanked by a brisk, contemporary rhythm section. In the tradition of bluegrass, their harmonizing with Maines could be close and cutting, and their vivacious spirit supplied extra punch. Maines in particular seasoned her performances with a Gen-X irreverence that was subtly revolutionary for country, and made their early singles — “I Can Love You Better,” a bluesy, breezy boast of prowess; “There’s Your Trouble,” an eye roll at a guy’s poor choice of partners; and “Wide Open Spaces,” a young woman’s restless yearning to enlarge her experience of the world — feel in step with their moment.

1999: On their way to becoming headliners themselves, the Chicks landed a couple of tour slots that reflect the varied audience they were building. Not only did they join the festival-style stadium lineups of George Strait, a paragon of stoic traditional country masculinity, the very same year they also became the first country headliners of Lilith Fair, pop music’s broadest gathering around feminist ideals up to that point. Their down-home, fun-loving displays of cheekiness and self-determination spoke to core country fans as well as those more accustomed to following pop stars and alt-rockers.

The Chicks didn’t drastically alter their formula for their second Sony album, 1999’s Fly, but they didn’t succumb to caution either. If anything, they featured Strayer’s banjo and acoustic and steel guitar and Maguire’s fiddle, viola, and mandolin even more prominently in the arrangements. Star status meant they now had their pick of song sources, and they embraced folkie singer-songwriters they admired, like Patty Griffin and Darrell Scott, and took on a greater writing role themselves. The turbo-charged rockabilly hoedown “Sin Wagon,” Maines and Maguire’s handiwork (along with their co-writer Stephony Smith), made acting out and kicking against constricting feminine codes sound like audacious fun, and its sarcastically coy references to “mattress dancing” generated mild concern at the label.

2000-2002: ‘Goodbye Earl,’ Lawsuits, and Pissing Off Toby Keith

2000: Murder ballads had long been a staple of old-time blues and folk lineages, and by the early ’90s, the domestic violence that went unacknowledged in so many of those ancient-sounding tales featured in a few chart-topping, contemporary country narratives. But there’d never been a story of getting revenge on an abuser that was as lighthearted as “Goodbye Earl,” by legendary, character-driven songwriter Dennis Linde. It was initially recorded, rather blandly, by an all-male outfit that never released it. Maines and her bandmates injected wicked wit into their telling of the tale of a bullying husband succumbing to the poisoned black-eyed peas served up by his battered wife and her best friend. In the Chicks’ hands, lines aimed at the villain became gleeful taunts, and the “nah nah nah” refrain a sunny-snotty singalong. The song was initially just another album cut on Fly, but the track generated enough interest to merit a memorably campy music video and official release as a single, though many radio stations were nervous about putting it in rotation. The Chicks’ performance, positing female friendship as the best line of defense, became a platinum-selling signature number.

August 2001: As a general rule, those who wanted to maintain good standing in the Nashville music community avoided airing their professional grievances too loudly and widely; they complained only in mild, diplomatic terms, if at all. But during a dispute with Sony over unpaid royalties, the Chicks didn’t hesitate to openly escalate it. They made a show of meeting with other labels potentially interested in signing them, and after Sony sued to keep them, announced they were filing a countersuit and joining an array of pop and rock stars, including Courtney Love, in a PR and legal crusade against onerous, long-term record contracts. The Chicks wanted their young, female fans to see them taking up for themselves. They hammered out an unorthodox agreement that mostly severed their relationship with Sony’s operations in Nashville and put the New York branch in control of their marketing.

October 2001: While the legal battle played out, the Chicks holed up in Texas and embarked on a homey, acoustic departure from their blockbuster albums with no label input or commercial agenda. It’s not at all unheard of for country stars to take on back-to-the-roots projects, but they usually save endeavors like that until they’re far enough into their careers to be past their hitmaking heydays and primed for nostalgia. But here were the Chicks, stripping away the radio-ready studio gloss, electrified instruments, and drums from the sound that still seemed to be paying off for them. They were simultaneously circling back to the string-band sensibilities they found formative and stretching out. Working alongside Maines’s dad, they received their first production credit for a polished, progressive bluegrass set, stocked with melancholy ballads and frisky romps, one of them instrumental. By summer 2002, Sony released it as Home and, for a time, country radio spun its singles, nevermind that they were acoustic.

August 2002: Nashville norms of decorum call for stars to behave amicably toward each other in public, but Maines dared go on the record condemning a major male hitmaker’s combative, post-9/11 show of patriotism. In a newspaper interview, she gave her unsoftened opinion of Toby Keith’s “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American)”: “It’s ignorant, and it makes country music sound ignorant.” Keith dismissed her opinion as invalid, since he’d authored his song and didn’t see her as a songwriter. From there, they got theatrical with what came to be recognized as a history-making feud. At Keith’s shows, the jumbotron displayed a satirically doctored photo of Maines cozying up to Saddam Hussein. When the Chicks performed on the Academy of Country Music Awards, she sported a shirt with “FUTK” emblazoned across it in DIY, sequined letters, an acronym which she winkingly — and unconvincingly — claimed stood for “Friends United Together in Kindness.”

2003: The Night That Changed Everything

March 2003: Midway through a London show on the first night of the Chicks’ European tour, with the American invasion of Iraq imminent and anti-war sentiment growing in the U.K., Maines offered a casual, crowd-pleasing aside between songs, a moment captured in the 2006 documentary Shut Up and Sing. “Just so you know, we’re on the good side with y’all,” she began, her eyes darting to the neck of her guitar as she positioned her hand to make the next chord. “We do not want this war, this violence.” She paused, checking her fingering once more, before looking up and delivering a punchline with playful disgust. “And we’re ashamed that the president of the United States is from Texas.” While the audience cheered and applauded, she grinned at Strayer and Maguire on either side of her, and they laughed. The footage provides a window into how casual those lines seemed to Maines when she spoke them, and to her bandmates and their manager, Simon Renshaw. That night, they toasted a successful performance.

In successive scenes of the documentary, Renshaw has to explain to his clients that he’s shut down the chat room on their website because Maines’s comment was quoted in The Guardian, amplified by U.S. media outlets, and seized on by right-wing web forums and conservative talk-radio hosts, who began mobilizing people to call in to country stations with complaints. It was at that point that the Chicks went from bemusement into crisis management. They made conciliatory statements apologizing for disrespecting the president, and emphasized their support for the troops, but the backlash only intensified. Lots of country stations, including KLLL in Maines’s hometown of Lubbock, instituted bans of the Chicks’ music, and a few even put on CD smashing events as stunts. On Fox News, Bill O’Reilly called the three “callow, foolish women” who “deserve to be slapped around” and Pat Buchanan declared them “the dumbest, dumbest bimbos I have seen.” All of this played out in the pre-social-media era, when scandals were metabolized more slowly. It mattered, too, that the radio industry had undergone a corporate consolidation and instituted more conservative and controversy-averse programming. 9/11 still loomed large in the national consciousness, and people were buying President Bush’s “weapons of mass destruction” justification for invading Iraq. Country music had had its share of riled and ruminative reactions in song, but in that environment, dissenting female voices weren’t tolerated.

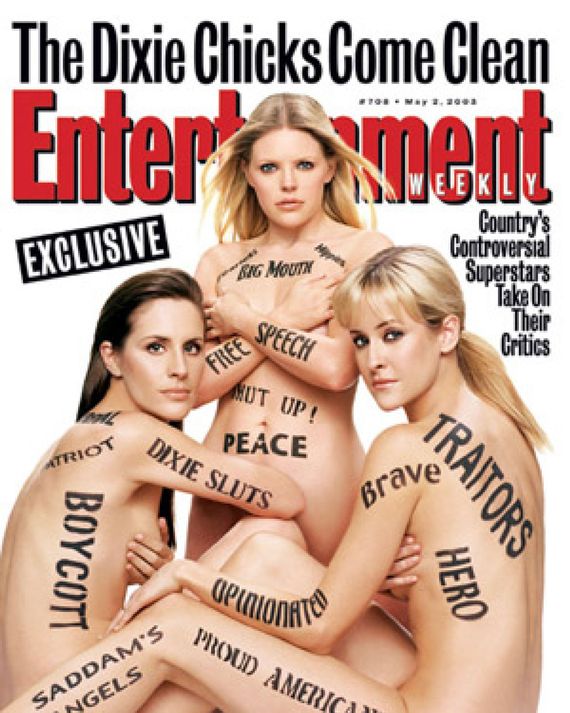

April 2003: The Chicks maintained a united front while absorbing unambiguously sexist insults and death threats. It was their idea — and contrary to their publicist’s advice — to draw attention to that treatment and the unrepentant stance they’d gradually adopted in response by posing nude on the cover of Entertainment Weekly with names they’d been called painted on their bodies, among them “Saddam’s Angels” and “Dixie Sluts.”

2005-2007: Not Ready to Make Nice

2005-2006: The radio dominance of even the biggest country stars tends to wane in middle age, but the Chicks’ sudden and punitive banishment bore zero resemblance to that pattern. Least surprising of that unflattering chapter in country music history was the way the trio leaned into the strong-mindedness that was already at the heart of its image. Maines, Maguire, and Strayer carried a justifiable sense of betrayal into the creation of their next album, 2006’s Taking the Long Way. Their decision to bypass both Nashville and Texas and work with Rick Rubin, a noted guru of artistic reinvention, on serious-minded, score-settling material, all of which they co-wrote with alt-rock sophisticates, signaled that they viewed their separation from the country-radio format, professional community, and cultural identity to be a lasting one. The album’s centerpiece, “Not Ready to Make Nice,” made an anthem out of the Chicks’ resistance to shouldering the burden of reconciliation.

2007: When the 2007 Grammys came around, the broader industry establishment registered its endorsement of the Chicks’ direction by voting “Not Ready to Make Nice” Record and Song of the Year and crowning the album in both the country and all-genre categories. But it was seen as confirmation of mainstream country’s rejection when the project failed to receive any nominations for ACM or Country Music Association awards, aside from a Vocal Group of the Year nod.

2016: Still Not Ready

June: The Chicks stayed mostly out of the spotlight for years-long stretches, getting on with their family lives and tackling modest side projects, all while fully aware that during their absence millennial and Gen-Z acts and audiences were getting on with the cyclical business of radically refashioning the popular-music landscape. Maguire shared in a 2016 New York Times interview that they feared they’d become obsolete — until they took note of the numerous younger stars covering their songs. Chief among them was Taylor Swift, but a slew of other acts, many of them in the country fold, could be heard doing their own versions of “Goodbye Earl” and other tunes, listing the trio as a prime influence on embracing nervy expression and incorporating naturalistic sounds in forward-thinking ways. The Chicks reconvened for a world tour that reflected how their own outlook on what belonged in their shows had evolved. Political satire was now just part of their backdrop — nobody missed the picture of Donald Trump with cartoonish devil horns — and in a setlist that drew heavily from the last two albums they’d made, they left room for their reading of “Daddy Lessons,” the most countrified track on Beyoncé’s recently released opus Lemonade.

November: The Country Music Association award show is big on acknowledging country music’s past and its present popular reach, and has an earnestly celebratory yet self-congratulatory of paying tribute to legacy acts and staging splashy crossover collaborations. But the Chicks ensured their return to the televised affair would complicate those gestures. The performance they worked up with Beyoncé conveyed a stronger sense of solidarity with her than country institutions and positioned them both as outsiders. They nodded to their places in a down-home, southern musical lineage, whose history of racial exchange and breadth of Black contributions has been obscured by industry segregation, with the “Texas” chant they passed between them. They gave prime billing to a string-band rendition of the pop-R&B dignitary’s “Daddy Lessons,” and tacked on an excerpt of “Long Time Gone,” a wry tale of country ambition-turned-disillusionment that had been one of the Chicks’ last, and least likely, country radio hits.

2019: Return to Music

August: It’s become common to hear progressive-leaning and quietly frustrated country acts refer to the prospect of being “Dixie Chicked” (i.e., attacked on ideological grounds), but since completing her passage to the pop realm, Swift has been especially vocal about how closely she’s studied and how highly she’s valued the lessons of the group’s journey. She acknowledged that kinship more formally by inviting the three to guest on her song “Soon You’ll Get Better,” one of the tracks on Lover that showed her returning to unvarnished songwriting from a confessional posture. The Chicks’ contributions were subtle — pillowy harmonies, banjo softly entwining with finger-picked guitar, delicate fiddle lines — but their presence was meaningful. It stoked interest in what else the trio might be cooking up with Jack Antonoff, the Swift co-producer that the Chicks were rumored to be sharing.

2020: Gaslighter

March 4: It wasn’t clear what Antonoff’s involvement actually meant for the mood and feel of the Chicks’ new music until the propulsive folk-pop of “Gaslighter” arrived this spring, just ahead of the pandemic lockdown. The track possessed a handmade quality and a massive, gleaming hook. The Chicks seemed to have found new life in their fun-loving, sharp-tongued wit, applying it to the lively belittling of a toxic, deceptive, ego-blinded ex. This time, it didn’t concern them in the least when some (incorrectly) interpreted the song as a swipe at President Trump.

June 25: The Chicks didn’t release any sort of lengthy, carefully workshopped statement the day they officially banished “Dixie” from their name. They simply explained, “We want to meet this moment,” and simultaneously rolled out a musical manifesto. The lyrics of “March March,” written before the Black Lives Matter uprising of 2020, swore off passivity and vowed to follow the lead of impassioned, mobilizing youth in the face of mass shootings and climate change. The music video updated the song’s sentiment, with montages of old and new protest footage (against racist police brutality and wars; for gay rights, women’s rights, and saving the environmental) and the names of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Tony McDade, and numerous other Black Americans whose lives have been taken by white supremacist violence. Sonically, the Chicks had found a protest style suited to their singular gifts. Maines stretched the bluesy, rawboned contours of an Appalachian-inflected melody over a minimalistic bass drum pattern and sonar-like pulse, here and there interjecting hip-hop-schooled cadences and smart-assed taunts. Late in the track, the group stoked powerful tension by layering on a martial snare pattern, syncopated clapping, flaring fiddle and lap steel licks, and precise banjo counterpoint.

It felt like an extension of the confrontational posture the Chicks have grown comfortable with in the wake of their unforeseen plunge into politics. Even if the “Dixie” part of their moniker hadn’t been pegged as problematic in their industry dealings and published reviews during the first many years of their fame, the name change also seemed thoroughly in character for them — and inevitable at a time when the music industry, country music especially, is reappraising its problematic messaging and racially exploitative practices, and people are pondering with new urgency what’s contributed to perpetuating racist wrongs. There’s really no way to divorce “Dixie” from its connection, deep down, to taking pride in the South’s old segregationist ways. The only small mystery was why musicians who grew into voicing their convictions after unlearning mainstream country’s codes of courteous avoidance took until June of this year to shed the word that, in the Chicks’ case, had troubled them some time in the 2000s. It would’ve been a massive undertaking to rebrand an empire, to be sure, but the Chicks had dealt with greater disruptions. Plus, their new moniker serves as a knowing reminder that they’ve met with, and called out, a phenomenal amount of explicitly and implicitly gendered contempt over the course of their career.

July: From a certain angle, Gaslighter, the album the Chicks have delivered 14 years after their previous effort, is their lightest work to date, its melodies winsome and daring and its textures a blend of imaginative, sprightly string-band flourishes and pop’s effervescent rhythmic patterns and cresting dynamics. On their own knowledgeable and unfettered terms, they’ve utilized elements of country and folk styles that still hold expressive possibilities and meaning for them. That’s not to say that the subject matter is carefree. They have convivially clever ways of bringing the wounds of duplicity (many of them marital, from the sound of things) to life, and an eye for tantalizing detail (the telltale sign of someone else’s left-behind tights, a backstage exchange with the other woman). They tease out complicated desires. They feel for those blindsided by betrayal before developing defenses, and that includes their younger selves.