“Barbara Gladstone rescued a beautiful dying species in order to become immortal.” So wrote curator-painter Francesco Bonami in an email last week, upon hearing that the internationally respected (yet still somehow underground) New York gallerist Gavin Brown, 56, was closing his gallery and becoming partners with Gladstone, 84, and her semi-mega New York gallery. It’s hard to map what the merging of two such important pre-COVID-19 galleries might mean in a post-COVID-19 world. But shock waves ripped through the New York art world on Monday when it was announced. It shook me — even as things seemed to be shrinking, this felt big.

Let’s start with what was lost. First, the gallery itself. Brown burst onto the scene in late 1993 when he rented Room 828 in the Chelsea Hotel to stage a show of the drawings of then-unknown 27-year-old Elizabeth Peyton. One went to the lobby, asked for the key, signed in, went upstairs, unlocked the door, and saw the show alone. The event lasted two weeks; around 50 people came. I was one of them. I remember how great it was, in that recessionary AIDS art world, to feel such new energy brewing. A friend told me he and his boyfriend had sex in that room; bands heard about the space and practiced there; parties happened. Nothing was stolen or damaged. Even if you didn’t like the work, a new freedom felt afoot here and elsewhere, including at similar events in London, Berlin, and Tokyo. A new band of artists, curators, gallerists, critics, magazines, collectors, and art fairs took the stage. It was as beautiful as it was desperate.

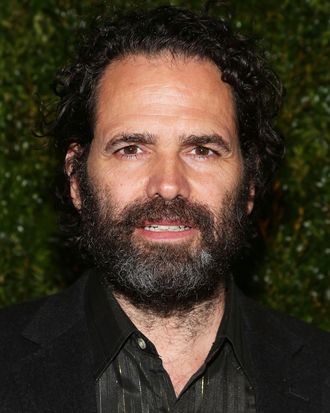

Six months later, Gavin Brown’s Enterprise opened in a teeny storefront gallery just steps from the Holland Tunnel. Brown represented Peyton and then-unknown soon-to-be superstars like Peter Doig, Chris Ofili, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Jake and Dinos Chapman, and others. Since then, he’s discovered and shown numerous artists, including Arthur Jafa, Urs Fischer, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Martin Creed. He has reinvented himself many times, served free food to visitors, opened a bar next door to the gallery; he’s always moving. Soon, he moved to a meatpacking place on the corner of LeRoy Street. When the rest of the art world doubled down in Chelsea or decamped to the Lower East Side in the mid-2010s, Brown rented and renovated four floors of an enormous old brewery in Harlem. We can only imagine the costs of all this for a gallerist whose sales were never as high as other spaces his size.

Brown is a special case in a class of special-case galleries and artists that emerged in the 1990s. He famously didn’t make studio visits and relied instead on listening to his artists. His gallery felt cultish — a cool kid’s club anyone could gain admission to if they had enough punk-bohemian allure. There were a lot of crazy people doing crazy things, which kept the gallery grounded in an older, more romantic idea of what the art world used to be. It was less like Warhol than his Factory. Amid the incredible success that came to this generation of new artists and dealers, Brown’s gallery sent a message of false positivity that said, “See, we can keep our underground cred while cashing in, making money, getting famous, traveling the world, starting new art fairs, and dominating biennials.” Collectors, artists, critics, curators — the whole art world bought into this. Of course, this couldn’t have been sustainable; we aren’t having it both ways. The players might have been “pure,” but the outcome only got more moneyed, hyped, gigantic, and inflated. A lot of great art happened — but so did a lot of bloat. For a little longer than all the others, Brown gave visitors the wonderful feeling that broke nobodies could make it in this world. But size and money displaced all that. Brown had to sell almost everything he had to renovate the Harlem space. Meanwhile, in an Instagram world where gallery foot traffic was already shrinking to a trickle, moving to 127th Street meant that many people in the art world — especially younger generations of critics — weren’t even making it up to his gallery. Great shows went unseen. Maybe unsold, I don’t know. Either way, making a radical move uptown in an art world that is no longer radical was, presumably, a bad decision and may have helped drive him to this point. The megagallery cash machine siphoned off his artists (Peyton had already decamped to Gladstone) the same way it did everyone’s artists. COVID-19 only revealed another fault line that had already been present before it arrived. Like other great old secret art world gardens that now hang in the balance, this one could not survive it.

Gladstone, meanwhile, has been a force in different guises since the 1980s. She has partnered with various people and galleries — eventually leaving and going her own way again. She staged Matthew Barney’s first New York solo show in 1991 and has since helped debut many international artists in the U.S. I had my work in Gladstone’s 57th Street space when I was a would-be artist (long story). That Barney show, though, was key to her development. While Gladstone was always respected, by the time Barney joined her gallery — after his own fledgling gallerist, Clarissa Dalrymple, closed the space she was running — she was a step behind the newer energies of the 1990s. Barney changed that overnight, and Gladstone has been a world force ever since — owning her own Chelsea space, teaming up with other gallerists along the way, and operating spaces in Brussels and on 21st Street and 24th Street. She has always tinkered with her stable with mixed results. Today, she is among the best gallerists anywhere.

I’ve known these two — Gavin Brown and Barbara Gladstone — almost my whole art life, so I’m an unreliable narrator. Offhand, we may say that she’s gone through several incarnations, seen artists come and go, always adapts, and currently represents a stellar stable of artists. He’s a singular visionary I might not let near a checkbook. I love that he may be on the front lines going forward. Either way, with numbers of great gallerists in their 70s, 80s, and 90s — among them Marian Goodman, Paula Cooper, and Larry Gagosian — this partnering seems to guarantee that one of them, in this case the Gladstone Gallery, will survive. Perhaps these two great gallerists were long-distance swimmers finally tiring. I want this to work, but who knows these days. If Brown left, would his ten artists remain? All these are questions for another day.

What this merging might mean for the bigger picture, however, is also not clear. The brilliant writer Kenny Schachter wrote to me: “This is the harbinger of unprecedented gallery consolidations and closures far outpacing the retrenchment after the 2008 financial collapse.” As for Brown, he writes: “Gavin made a few unfortunate mistakes”—the uptown move—“that cost him his autonomy. I love him but it may be arrogance for him to think ‘my minions will follow me to the end of the earth … and throw their money at me like blind adherents to Scientology.’”

Let’s take stock. Right now, given America’s disastrous mismanagement of the coronavirus, galleries that were hoping to be open in June or July are now facing the prospect that this semi-shutdown may extend indefinitely (especially with flu season approaching). Those that got PPP loans have now gone through them; those that didn’t are hurting worse. Galleries that were on their knees already are negotiating rent relief for spaces in buildings they primarily don’t own, working out payment plans with storage and shipping companies, and laboring remotely every day to eke out sales under near-impossible conditions. It’s a delusion to imagine that in this country we might all soon return to pre-COVID-19 normal. That “normal” wasn’t even normal in February, and it’s already gone. But this isn’t the closing of a gallery that everyone imagined was on shaking foundation — it’s the closing of a gallery that was, in a profound way, the very self-image of the contemporary art world. People might wonder, If Gavin can’t survive then who can? What can? In which form? At what cost? Why?

The resulting shakeout is likely to widen the gulf between the haves and the have-nots. For a while — thanks in part to Gavin and Barbara — we allowed ourselves to think there were more categories and kinds of galleries. But it was lunacy to call galleries like Gladstone, 303, Bonakdar, Petzel, Kreps, and Bortolami “mid-tier” or “middle-sized.” Only the gigantism of the handful of worldwide megagalleries — some great, others only okay or one-stop-shopping, big-box stores — made it seem so. Sadly, the market (and many others) subscribed to this delusion. Money and attention were unequally heaped upon this upper strata of megaoperations.

Meanwhile, artists represented by the aforementioned galleries followed the honey scent of bigness and money to the bigger galleries (and they may continue to do so now with money growing tighter by the hour). Those mid-tier galleries are in the business of risk and discovery. Most of the megas don’t so much produce culture as consume it. All this has exacerbated the system’s preexisting crises — obscene prices, auctions, nonstop travel, hype, and continuous art fairs; everything was out of whack, top heavy, sick. Even today, in our shutdown world, it galls and astonishes me that much of the online coverage of galleries is devoted primarily to megagalleries. We see lists of what sold in online auction; prices are touted. Stories tend to be about either unknown or (mostly) ultrafamous artists — all this with very little actual criticism, and almost nothing that isn’t said to be “good.”

Are mergers an answer? Can galleries like 303 and Bonakdar, for example, merge? Or can a larger gallerist like Paula Cooper or Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn partner with someone like Kreps, Bortolami, Miguel Abreu, Metro Pictures, Luhring Augustine, James Cohan, or Sikkema Jenkins? What’s the upside (apart from becoming another “beautiful dying species”)? Those partnerships only mean that money is consolidated, more artists are left without galleries, and people who work at galleries will be out of jobs, on the ropes. This is why I don’t want to believe that Gladstone-Brown represents a wave of the future, and also why — as much as I love and admire them both— I wish it weren’t happening. Maybe Gagosian or Hauser & Wirth, already galleries the sun never sets on, will absorb or “partner” with some of those other spaces — but to what end? Maybe we’ll all work for them. But work at what? Why? These sorts of moves make those galleries seem like dinosaurs, even if they’re the ones that find a way to survive.