Starting this week, the free Tuesday editions of Hot Pod are going to be syndicated as a weekly column on Vulture as part of our expanded podcast coverage, which you can read more about here. For the uninitiated, Hot Pod is an industry-leading trade newsletter about podcasting by Nick Quah. In each issue, readers can expect news, analysis, interviews, gossip, and more.

A Note From Nick:

This is exciting, but unfortunately, it also means that Hot Pod will no longer be syndicated on Nieman Lab (a great website). I’d like to take this opportunity to express my deep, deep gratitude for Joshua Benton, Laura Hazard Owen, and the rest of the team over there — like Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga, they plucked me out of obscurity when Hot Pod was a wee tiny newsletter, and I genuinely doubt I would’ve gotten anywhere if it wasn’t for their constant support and validation. I’m very, very proud to have been part of the Nieman Lab family.

Despite the move, nothing else really changes with Hot Pod. This remains an independent operation, I continue to own and do what I want with it, and I’m still a free agent, more or less. On a logistical note, there will continue to be Insider newsletters for paid subscribers every Thursdays and Fridays, as we remain built on a direct revenue model. (Speaking of which, become a paid subscriber today!)

Also, my work on Servant of Pod continues. More on that later.

It’s just that I’ll be doing a lot more work under the Vulture banner, including writing 1.5x Speed, that new podcast recommendation newsletter I told you about last week. (If you haven’t already, you can subscribe here.) It will take me a few weeks to settle in and get into the groove with that newsletter — which, by the way, will be owned by Vulture — but I’ll get there. In the meantime, send me your picks and press releases.

One last thing before we move on. Here’s some recent stuff I wrote for Vulture:

➽ A long interview with the great Karina Longworth of You Must Remember This.

➽ A review of Serial Productions’ Nice White Parents.

Okay? Okay! Let’s go.

Supporting Cast Launches Dynamic Subscriber Messaging Feature

Incremental innovations around the podcast feed will always be interesting to me, even if, well, they’re a little dry.

Supporting Cast, the direct podcast revenue company spun out of Slate, announced a new feature today that would allow publishers using its platform to send targeted personalized audio messages to listeners.

The main metaphor here seems to be email newsletters, as it appears to cop a function that you’d expect from something like, say, Mailchimp. Much like how you can prewrite messages that will be automatically delivered to certain segments of your mailing list depending on the context — say, a “heads up, your paid subscription is going to expire, please update your credit card” note for expiring accounts — this feature will theoretically allow podcast publishers using premium tier business models to hit segments of its paid subscription base in similar ways.

The company is mostly billing this new feature as a relationship management and engagement tool, but I reckon there’s room here to try out some stuff creatively. As the vessel that mediates the creator-listener relationship, the RSS feed remains under-exploited for its creative potential, and I feel like this tool can set the stage for some truly interesting experiments.

➽ Audible breaks out separate pricing plan specifically for its exclusive programming. Seemingly wonky, but there’s quite a bit here, I think.

First things first: this new plan is called Audible Plus, and with a $7.95 per month price tag, it’ll offer subscribers access to its exclusive podcast and audio programming. That content library includes a bunch of celebrity-led stuff they’ve been piping in for a while now, but also audio shows from big media operations like the NBA as well as studios that would otherwise be making stuff for the more conventional podcast ecosystem, like Pushkin Industries. Interestingly, Wondery will also be supplying some of their existing shows to the service, though stripped of ads. (Side note: between this, a random standalone listening app, and whatever’s been going on with CEO Hernan Lopez’s legal situation around the FIFA bribery scandal, Wondery’s fast becoming one of the more strange and confusing podcast operations in recent memory.)

Anyway, the roll-out of Audible Plus also comes alongside another new plan: Audible Premium Plus, which is a consolidation of what were previously the Gold and Platinum plans that’s now priced at $14.95 a month and gives subscribers access to both original programming and the traditional audiobook offerings they’ve come to know and maybe love. That’s a whole lot of nomenclature, and for a more formal write-up, head over to The Verge.

Here’s the bigger picture as I see it: with Audible Plus, we’re talking about something that looks like a paid audio content platform operated by a massive and deep-pocketed company, one that concentrates on distributing original content commissioned specifically for its purposes. Audible Plus is precisely the product Luminary was supposed to be, and frankly, it’s the version that has best runway of actually pulling it off.

But let’s not gloss over Audible’s notoriously on-again off-again history with original podcast-style content. As mentioned in previous newsletters, Audible used to operate an in-house original programming team led by Eric Nuzum, which published some pretty interesting podcast-like work before a mysterious executive shuffle led to that team being laid off. The platform then pivoted its original programming strategy to a glitzy “audiobooks but without the book” model, profiled here in the New York Times in the summer of 2018, before iterating out to what now genuinely appears to be a Netflix-like approach, in which the platform signs development deals with various audio production studios.

One intriguing thing is that they appear to be explicitly using the word “podcasts” to market these original audio products, even though Audible seemed to have historically rejected the use of the word to describe its original programming a few years ago. In any case, it’s a nomenclature that some corners of the podcast would reject due to the fact that those shows live behind a paywall, and are not distributed as part of the open ecosystem. (Similar critiques have been levied at Spotify for its own use of exclusivity around podcast programming.) Chalk this up to Audible’s Amazon heritage; diplomacy is rarely the concern of companies of this size and nature.

➽ Meanwhile… iHeartMedia has deepened its relationship with Newt Gingrich’s media company, called Gingrich 360 (oddly enough), through a multi-series production deal that’ll add four new conservative leaning podcasts to the iHeartMedia podcast line-up. Those shows will apparently feature millennial and Gen Z hosts, and are ostensibly meant for the “next generation of conservatives.”

Because if there’s anything millennials and Gen Zers like, it’s Newt Gingrich.

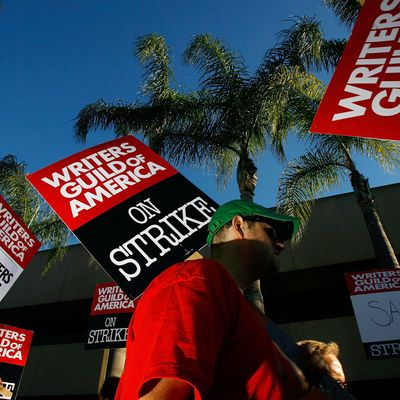

The State of Collective Bargaining in Podcasting

Way back in the pre-pre-COVID days of March 2019, a consortium of creative workers at Gimlet Media announced that they were moving to unionize with the Writers Guild of America East. The development turned many heads in the podcast community at the time, even coming off as genuinely confusing to some. (An email I received at the time read: “Can they do that?”) While union pushes at digital media companies were a known phenomenon by then, podcast-specific companies felt like a separate story, like they were an entirely different of organization. That such a company, particularly one that was venture-backed, was unionizing felt radically unexpected. There was some element of drama as well, as the news came shortly after it was widely announced that Gimlet Media was going to be sold to Spotify. In the heat of a sale, the message that staffers were sending seemed clear: getting bought is great and everything, but we’d like to have some input into how this new arrangement is going to work, given that our labor helped build this place.

Gimlet wouldn’t be the only podcast concern whose staffers would unionize that season. Not long after, the workers at The Ringer, Bill Simmons’ podcast-centric digital media venture (which would also later be sold to Spotify), similarly voted to form a union, flipping what was a curious development at Gimlet into the possible start of a trend. Both unions were eventually recognized, and both are now in the bargaining phase.

It’s worth noting that many of the digital media companies that moved to unionize by the end of 2019 — BuzzFeed News, Slate, HuffPost, Vox Media, and so on — are active podcast publishers themselves, but what happened at Gimlet Media and The Ringer introduced a key idea to the digital media labor narrative: that audio is also a crucial component in digital media work, and they should be recognized and protected as such especially as the media universe in totality remains in flux both from a structural perspective (streaming, disruption, and so on) and, at this moment, due to the pandemic.

Unions are a fact of life in digital media these days, and from where I sit, one of the more intriguing aspects of this is the fact that a good deal of this organizing work involves building a union culture in a space that previously didn’t have a lot of it. Which isn’t to say that audio and podcasting was devoid of collective action up to this point — notably, NPR’s labor force has long been represented by SAG-AFTRA. Still, unions in podcasting is a very new concept. At least, they’re a very new concept to me, speaking as a millennial who has known nothing but a brutal, broken professional world. So thought I’d try to get a better grasp of what’s been happening with the union push, and what it all means for audio workers.

To that end, I reached out to the Writers Guild of America East (WGAE), and I was given the opportunity to speak with Lowell Peterson, the executive director of the organization. Here’s that chat:

Hot Pod: How many podcast shops are working with WGAE now, and where do those organizing efforts stand?

Lowell Peterson: We’re working with at least a dozen unionizing podcast shops. That includes companies that really concentrate on podcasts, like Gimlet and The Ringer, as well as digital media companies with significant podcast operations. We’re also talking to a lot of other companies in the podcast space.

I should note that there are a few different forms of podcast shops, and the ones I’m talking about mostly deal in “nonfiction.” They don’t typically work in dramas or comedies, though we are working to organize in that space too. For the most part, they all involve written work, so the process is not unusual for us, because we have a lot of experience organizing with writers in the film and television space.

Of course, the podcast space is growing, as I’m sure you’re very aware of. People are listening to more and more podcasts, and because of that, companies are committing more money to the medium. They’re trying to figure out how to develop more shows and maximize the number of listeners so they can monetize them. We’re paying attention to all that, and we’re seeing a real eagerness among the podcast community to get engaged in collective bargaining. As the work gets more intense, I think people recognize they want the benefits of unionization.

HP: It’s interesting that you talk about roles in podcasting as being familiar and somewhat analogous to television and film. In my mind, the podcast labor force remains fluid in a lot of ways — there’s still some amount of non-specificity in terms of what being a “producer” means and what that job role tends to involve. Does that newness come across when you’re organizing podcast shops, or have film and television been sufficiently useful metaphors for the most part?

Peterson: Honestly, it’s a bit of both. Keep in mind: because of streaming, film and television are also going through a transformation in how they’re being produced these days. It’s not like the old days when everything was CBS or ABC or NBC, when all shows had long prime time seasons. Today, everything — employment, career models, and so on — is in flux throughout the film and television industry. That experience has been useful to us in the podcast world, because we’re accustomed to working with people who are trying to make the road by walking on it.

Everything might be in flux, but one of the things that collective bargaining can do is increase transparency in terms of how much you should get paid, what work you can do, and how you can advance up the ladder of experience. We also represent a lot of people in digital and broadcast news, and those fields are really in flux. It used to be that you could work for the same company your entire adult life. That’s not true anymore. A lot of people are hired on a project by project basis or per diem basis. That experience of developing new models as core industries are transforming is useful, because when it comes to podcasting, we’re organizing in an industry that has never had much unionizing before.

We’re also finding that there’s some variation from company to company. Some podcast companies have a regular bullpen of producers, writers, and associate producers who stay on payroll and transition from series to series. Other companies are more production-specific. You get hired to work on one series, and when that’s done, maybe they’ll hire you for another series, maybe they won’t. So we’re trying to grasp the best way to represent writer-producers in both models.

HP: Could you walk me through specifically what WGAE does in the organizing process?

Peterson: So, the process is very member-driven. We have a lot of contacts through the space, and when we organize a place, it tends to be a situation where the people who we represent are already talking to people working in non-union places. They’ll come to us and say: “Hey, I noticed that I know this person over at shop X and they’re having an issue with such and such, why don’t you talk to them?”

Then we talk to them, and if there’s interest in unionizing, we set up meetings and help the folks doing the work to reach out to their colleagues, put together an organizing committee, and talk through the issues. We rely on the employees of a company to talk to their colleagues, assess the level of interest, and figure out what the issues are. We also have a very talented organizing staff who knows how to help them, if they need it.

We encourage the actual employees at the company to take ownership of the organizing campaign. That’s really essential. But we also help them understand that they’re not just organizing by themselves — they’re joining a 7,000-person union that knows how to organize and negotiate. We bring the solidarity of the people at a large union. We let them know that they’ll be joining a real professional community of creative professionals.

So those employees organize, and if we have a substantial majority, we’ll go to the company and say, “A substantial majority of your writers and producers want to negotiate a contract with the Writers’ Guild. Will you please do this voluntarily?” Almost always, the company says okay. They’re not ringing church bells or singing “huzzah!” or anything, but more often than not, they recognize the union.

HP: Has there been any hostility, though? My impression is that unionizing efforts in the podcast and digital media industry has been somewhat smooth for the most part, and whenever there was friction, it seemed to mostly come out of a sense of unfamiliarity.

Peterson: I would say that’s right. There have been some important exceptions, but I think “unfamiliarity” is the right word.

A lot of the digital media and podcast companies, they don’t know what it means to have a union. They have a generalized sense of what the labor movement means, but they don’t really know. Many of these companies are really new, and their own HR experience is pretty limited. Often, though not always, the management are folks who were involved from the beginning of the company, and they started those companies with a business vision but haven’t necessarily thought much about things like pay scales and job classifications and employee benefits.

They might be anxious about the process, so it’s useful that one of the things we bring is a meaningful voice from their employees. We help them say: “These are what our concerns really are, this is how the job could actually improve.” In most cases, it’s been a pretty productive experience for managers, I think. Now, there has been some hostility. Hearst, for example, fought us tooth and nail. That was an actively hostile company, but we prevailed and we’re going to start negotiations soon. But most of the companies have not taken a strong anti-union stance, even if they do get a little freaked.

This has to do with the organizing model we use. Once we have gotten to the point where we go to the company and tell them their employees want to unionize, we’re really sure of it. So if a manager tries to take a temperature read, they’ll know this is serious, and that their employees have really decided they wanted to engage in unionization and collective bargaining.

I don’t want to be corny and say resistance is futile… but it is. By that point, people have already spent months thinking about the issues, talking to their colleagues about the issues, and making a commitment to unionization. So even if you get an employer saying, “No way, you don’t want that, you don’t know what you’re talking about, you don’t want a union here”… they never prevail. By the time we start talking to the employer, the unionization effort is already real and has deep support. We do the patient work of organizing in advance.

HP: What have been the more consistent issues that have popped up in the organizing efforts? Or are there major differences from shop to shop?

Peterson: There are definitely themes, though there are certainly specific issues at specific shops. I would say transparency is a major theme, and that has several iterations: transparency in the job titles, job duties, pay rates. Sometimes job roles were improvised when they shouldn’t be. Another major theme is having a voice in big decisions, and that’s related to transparency. Folks don’t want to open their email or Slack channel in the morning to find out that their benefit plans or the ways they do the work have completely changed. They want to have some ability to participate in the decision making on basic workplace issues.

I would say equity and inclusion issues pop up at every shop. There’s a real commitment to workplace culture and more diverse hiring at all organizations we work with, both from a social justice perspective and quality perspective. Podcasts are just better when you have more voices and more experiences engaged in writing and producing them.

So those are the main ones. Obviously, pay rates and benefits are important to everybody as well. There’s no question that when we go in, we know we have to lock in the best possible benefits and get pay straightened out, make it more equitable and make it better.

HP: Has intellectual property been a big part of those conversations?

Peterson: Yes, absolutely. In the digital news space, we’ve negotiated some pretty innovative protections, mostly for when somebody’s article or short video gets turned into something longer.

In the podcast space, you’re already in a place where the underlying intellectual property is being exploited in a longer form. Having some sort of ability to continue with a series, having some ability to create your own work from what you’ve learned in working on the podcast… those have been priority issues as well.

This is important in the nonfiction space, but it’s especially important in the fiction space, because so many companies are using podcasts to test drama and comedy ideas for Netflix or network TV. It’s a cheap way to develop intellectual property, and we want to make sure the writers and producers can share in that.

I will say it’s been tough. It’s an uphill battle. Intellectual property issues have featured heavily in all of our negotiations. Now, we’ve made gains, but I don’t want to pretend that every producer or EP owns the copyright of their show, because that’s not true. But having some ability to share in the fruits of the creative labor and maybe even exploit it on your own or stay with it either financially or creatively if it becomes something bigger… yes, that’s definitely been an issue.

HP: How has the pandemic affected membership and the organizing process?

Peterson: In many ways, the pandemic has made it more difficult and more simple to do this work. The logistics of getting committees together is actually pretty straightforward now, because everybody’s accustomed to doing Zoom calls in the middle of the night, you know?

Our membership continues to grow. Employees opportunities haven’t been hit quite as hard as they could have been, but there have been some difficult spots. For one thing, advertising revenue has been drying up, and we’ve seen layoffs and furloughs among digital news shops. Another point of difficulty is the questions of employees being to do the work safely, particularly if they have to go out in the field to report or if they have to go into a newsroom setting. We’ve spent a lot of time trying to negotiate protocols that keep people safe.

We’re seeing increased interest in organizing. I think people feel anxious about the economy as a whole, and what it might mean for their employer. They want to have a voice in keeping their jobs or preserving benefits or getting severance pay if, God forbid, they get laid off. And as I was saying, because people can meet over Zoom or BlueJeans or whatever, the process of organizing hasn’t really been affected. We’ve been able to have lots of meetings with lots of people who do this work.

But again, I think that anxiety is only part of why we’re seeing an increased eagerness. It’s also because organizing is a way to have a voice. As both the pandemic and the podcast industry’s growing pains affect careers, it can be pretty daunting for an individual worker to face all this totally by yourself. If you’re facing it from a unionized perspective, you at least have protections and a voice, and some power behind you.

I’m pleased that people are eager. We’re actively organizing now in some podcast companies, and it’s been inspiring as a labor movement person to see people committing to collective bargaining because I do think it makes a difference in one’s life, one’s satisfaction on the job, and one’s ability to have some say both creatively and in terms of workplace decisions. It’s also nice to welcome folks into the broader Writers Guild community. Our members are really excited about welcoming new voices, new members, and new perspectives.

We’re very excited and enthusiastic about the podcast world. Of course, everything is very much in flux and that’s kind of scary, but that’s when you need to have a collective voice.

Lowell Peterson is the executive director of the Writer’s Guild of America East. You can visit the WGAE’s website here.

How Has the Pandemic Affected Physical Podcast Spaces?

By Caroline Crampton

Building out a physical space associated with a podcast business used to be a really good idea. For one thing, it offers an alternative revenue stream — through studio rentals and in-person events, among other things — that could check against the growing but volatile advertising revenue pool. It’s also a really good fit for any podcast operation built on a sense of community. Having a physical space for listeners to routinely gather can really strengthen that relationship between publisher and fan, expanding the notion of how that community can be served.

Or at least, it was a good idea, until, you know, the pandemic. Four of the biggest hit sectors by lockdowns and stay at home orders around the world have been live entertainment, hospitality, in person retail, and office space providers, and these also happen to be four of the ways in which podcasters were incorporating brick and mortar spaces into their business models. Events, cafés, merch shops and co-working spaces are all popular additions for networks and collectives, as are recording studios, of course. Whether these were of long standing or just recently opened, come early March this year, they all took a hit.

Now that it’s been about half a year since the lockdowns began in earnest, I wanted to check in with some of these businesses and find out how they were faring. In the UK podcasting scene, one of the more high profile stories in this area recently concerned Great Big Owl, an independent podcast network with an office and studio space in central London.

Joel Morris, a co-founder at Great Big Owl, recently tweeted that the company is now in a contractual bind with regards to their premises. He told me that the venture’s business model and whole way of working had been upended overnight. “We used to go in every day to an office, people would hire that office from us, so we had a business income from letting people use our facilities. And every day was processing recordings, giving them to people, welcoming people in, arranging people, setting up microphones and things,” he said. “Then overnight it disappeared and the office space we were hiring became an albatross around our neck because there’s no way of getting out the contract.”

The studio and office space are too small to make it possible to reopen with social distancing measures in place, and the company is locked into a contract until June 2021, Morris explained. Their landlord offered to move them to larger premises where they could open safely, but that would mean paying a higher rent and Great Big Owl is “a shoestring operation”.

The studio has suddenly gone from being the company’s biggest asset to being their biggest headache. “It’s just draining thousands of pounds a month out of the company at a time when not only can we not hire it out to other people, we can’t make podcasts of the quality we used to make using those facilities and also the advertising money has fallen through the floor,” Morris said.

Things were slightly more hopeful with Alan Bennett, who runs the HeadStuff network and The Podcast Studios in Dublin. The space, which comprises several studios, events spaces, offices and a café, was closed completely for three months, although the team were working on remote recordings and editing from home. Since Ireland has reopened somewhat in the last couple of months, they have been able to repurpose their largest room into a COVID-safe recording space for four people, each with two metres space between them, as well as having solo clients in to record voice overs or host webinars.

One of the biggest challenges, though, has been just communicating that it is possible to use the space safely when plenty of companies are still keeping their workforces completely at home. “We’re doing all the regulations, we’ve got hand sanitiser and two metres separated out, and we’ve got fresh air coming in and all those kinds of things. But if they’re not coming into town, we’re not gonna get them in the door,” Maguire said.

Although his company has stayed afloat remotely via their editing and consulting services, they are also now shifting their model somewhat to account for the restrictions on using their space. The HeadStuff network has previously worked with advertising and some Patreon-style crowdfunding for individual shows, but in the next few weeks they will launch a bespoke membership system that will allow listeners to pay €5 and pick up to three shows from the network that will share their contribution. The network will take a €2 cut for their production and running costs, and then the nominated shows will share the rest. “We’re hoping that this will help big and small podcasts [on the network],” Maguire said. “People might support one or two podcasts this month, and then next month when they’ve discovered one of the smaller shows, they might shift their support there too.”

Christopher Plant, founder of the RADIOKISMET podcasting space in Philadelphia, told me that the recording and events facility had grown naturally out of the needs of his co-working clients. It’s really ramped up recently: “I have two of my own podcasts, and then we produced probably fifteen other new podcasts in the last nine months,” he said. With the onset of the pandemic, the co-working side of his business naturally took a hit — “we’re probably operating at 25 percent revenues right now, which isn’t great” — and he’s now looking to move more towards content production in the future than purely trying to rent space.

They have four shows launching this autumn, some of which are monetised and some of which are outreach or part of a larger offering. The idea, Plant said, was to move more towards a “social club meets chamber of commerce meets incubator meets workspace and really build more heavily on the social component behind this.”

The overriding theme in every conversation I’ve had about this was how people are evolving their models like this, fast. These businesses can’t wait around to see what happens in the next few months and hope that recording in studio or attending in person events switches back to being the norm after months on Zoom — they need to get revenue coming in again now. Diversifying, it turns out, whether that’s via remote content production, direct listener support, or a bigger advertising push, matters more than ever.

➽ In tomorrow’s Servant of Pod: I speak with Richard Parks III, the one-man operation behind Richard’s Famous Foods Podcast, which, I assure you, will be one of the stranger things you’ll ever pipe into your earholes.

Richard’s Famous Foods is ostensibly a food podcast, something that could be said as being in the vein of Gastropod or The Sporkful, but it’s not really that. Rather, it’s a cross between a cartoon and a gonzo documentary series, which is a mix you wouldn’t naturally expect from podcast-land, as there simply isn’t very much of either in the medium. I first wrote about the show for Vulture late last year, and I’ve only grown to appreciate its borderline unsettling inventiveness more and more.

Two things stand out to me about this conversation. The first is how Parks talks about the show’s cartoonish aspects as a problem-solving tool — that is, as a way to get around using traditional and often tired methods of narrative exposition. The second is the extent to which Parks’ independent situation with the show made me think about the relationship between business models and creative experimentation. This isn’t just a show that would be hard to sell ads on, it’s also a show that probably wouldn’t be as good if it had to be run through, say, a manager.

Anyway, that’s tomorrow’s episode. You can find Servant of Pod on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or the great assortment of third-party podcast apps that are hooked up to the open publishing ecosystem. Desktop listening is also recommended. Share, leave a review, and so on.