Not everyone in the new book Young, Gifted and Black is young. “This book is just another way to examine and to produce Black space,” says writer-critic Antwaun Sargent, the book’s editor, in a joint interview with collector Bernard Lumpkin, whose extensive collection it is based upon, over Zoom. “It’s grounded in this generation of Black artists, from Eric Mack to Kevin Beasley to Jordan Casteel to Jennifer Packer, and then you see their predecessors.”

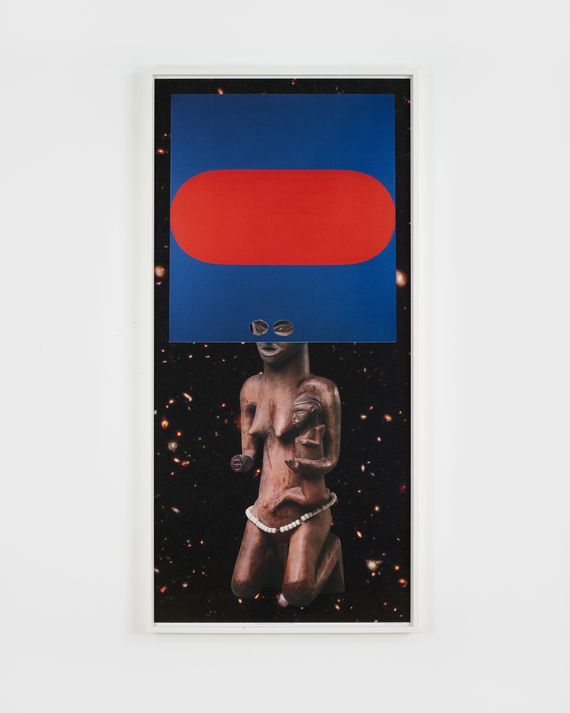

Looking back on the past decade and the explosion of Black art in the mainstream, Young, Gifted and Black surveys the next generation of Black artists, but with an eye toward the generation just before. It started out as an essay, and grew into a traveling exhibition, and now this 200-plus-page tome about “how these new voices are impacting the way we think about identity, politics, and art history itself.” The book, out September 22, contextualizes the collections of Lumpkin and Carmine Boccuzzi, and features critical and personal essays from curators, collectors, writers, and, of course, artists, including Rashid Johnson, Kerry James Marshall, Mickalene Thomas, and more.

There are essays from Thomas J. Lax, a young curator from MoMA, and Jessica Bell Brown, a curator at Baltimore Museum of Art, as well as the Studio Museum’s Thelma Golden in conversation with Lumpkin about the lineage of Black collection and patronage. Then there’s text from artists themselves: Jonathan Lyndon Chase writing experimentally about their work, Jordan Casteel on her connection to Lumpkin (some of Casteel’s work from Lumpkin’s collection is on view at the New Museum) and her wider work, among others.

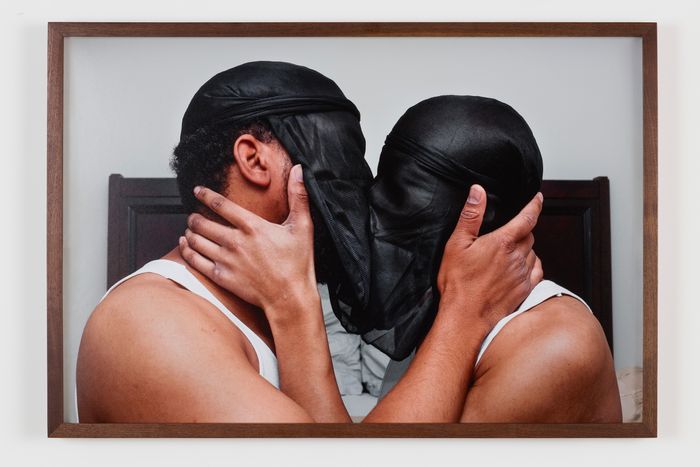

Lumpkin says his mission-driven approach to collecting was shaped by his parents. “I use the art collection — which grew out of conversations with my father, who was African-American — as a tool to educate people about black history and culture,” Lumpkin wrote via email. Many of the works at his Tribeca loft are about family. A photograph by D’Angelo Lovell Williams, a portrait of the artist and his mother, hangs in the entryway. Henry Taylor’s The Sweet William Rorex, Jr., a painting of the artist’s nephew, is prominently displayed in the dining room. In the living room, there’s a work by Tomashi Jackson and another by Kevin Beasley, a semi-figurative specter structure sculpted with resin and a house dress that Lumpkin’s son, Felix, likens to Harry Potter dementors. Outside the bedroom is a classic Leonardo Drew composition, filled with found knickknacks and objects like baseballs and baby rattles: “Whenever I walk by this artwork, I see something different, you know,” says Lumpkin. “We’ve had it up for years and the children see something different in it too. I think as they get older, they notice different things.”

Here, Lumpkin and Sargent in a conversation with Vulture about the book and how these groundbreaking artists and their work gives us a richer, deeper, and more complex view of the Black experience.

Where does this book fit into our current moment?

Antwaun Sargent: It’s the passing of a baton. I think about the moment that we’re in now where we have disproportionate Black death, disproportionate Black suffering, but then we have what has been considered a sort of renaissance in Black artistic production. I think that very often when we are in these moments that we don’t consider how we got to them. On the one hand, you’ll have people think of the killing of George Floyd or Breonna Taylor or any of the long list of names that we can name here as something new. And they kind of sort of erase Trayvon Martin, they erase Mike Brown, they erase these recent names, not to mention Emmett Till. This happens also with Black art.

So this is a history which needs to be written.

AS: What was so important about this collection and this book is that you can clearly see the links from one generation to the next. The book is grounded in this generation of Black artists, from Eric Mack to Kevin Beasley to Jordan Casteel to Jennifer Packer, and then you see their predecessors. That arc of history and how it informs the present is so important when we’re talking about Black artistic production but also the larger sort of social context.

When you were talking about Black patrons and Black collectors, there’s a long history dating back to the early 20th century with Alain Locke. You have these patrons collecting, preserving, donating, financially assisting artists so they could do the work and produce Black visual culture. Our culture is deeply sort of indebted in the history and the struggles that became before. Part of it was not just doing a book with my voice, or Bernard’s voice, but to bring the community into it. This book is just another way to examine and to produce Black space.

In what way?

Bernard Lumpkin: I was just reading this article from The Art Newspaper about how the art industry is grappling with systemic race inequality. It talked about how museums and galleries are doing this sort of “performative wokeness,” which is like a Band-Aid response to the real, hard, deep-seated structural issues around inequality and inclusion. When you ask about the gaze, the people in power often in the art world are still — even though we have more producers and more product that represents a broader perspective and more diverse voices — the structures, which are deeper and more ingrained are still in the hands of a certain few people and a few kinds of people. That being said, I think I’m really excited that there is an active dialogue right now around thinking about how we can change some of those structures and systems so that the power and the gaze is coming from different places in different people.

And it’s already affecting the more mainstream discourse: Amy Sherald just did the Vanity Fair cover, and Kerry James Marshall and Jordan Casteel did Vogue.

AS: We’re living in a world where Black artists are increasingly driving the conversation visually. What we have to remember is that before this moment there were people like Bernard, like Thelma Golden, and other curators and writers who really believed in this work. That requires a level of belief in the power of Black art, in the power of it to represent a community, to push back against stereotypes and racism, and to provide an intervention into the Western art historical canon. Because, frankly, before this moment, there was very little money to be made. It really was about a belief in the power of these artists to illuminate a community. By the way, I remember pitching Vogue around Jordan’s work five years ago and being told that it wasn’t a very Vogue.

This book pulls back the curtain on the art world and what Black art and artists get shown.

AS: One of the things that’s so unfortunate about the art world is that it’s so opaque. We don’t know — and it’s also by design — how things end up on museum walls. We tell this bullshit story about taste and beauty and this being the best one, and it often does not work that way. This book also helps to demystify part of how this work ends up in museum collections and exhibitions.

Bernard, you also know firsthand what those board meetings are like.

BL: Being someone who supports artists of color and being part of this Black art community is to sort of break down that conception about the art world, that it’s private, that it’s exclusive, that it’s restricted. It’s a conception and it’s also a reality. Those decisions that happen behind museum doors about what gets shown — I sit in those meetings and I know I can speak to that. It’s often the decision which has to do with whoever has the most clout in the room that day and can support and argue for an exhibition. I feel that by breaking down some of those ingrained sort of pathways to exposure and by broadening the road as it were and introducing other paths, I think that’s really important.

This collection is also very personal to you.

BL: For me, collecting artists of color was something that was true. It was genuine to my own experience. I have been able to tell a story about my own family, my own heritage. It’s not like I’m just collecting artists of color because it was fashionable. My purpose with the collection has always been to sort of tell a story — these voices that helped me answer questions that I’ve always had about race, about family, about what it means to be American, about what it means to be Black — and then take that story to a wider audience.

All of the artists in this book are recognized as significant, groundbreaking artists in their field. They also happen to be artists of color. They also happen to have to be young, and they also happen to have a voice, which is very much shaped by the moment and the politics of the moment. This book would be important regardless of the fact that the artists are Black, regardless of the fact that it’s a political moment. This book is also just about artists that are considered important today. But you add into that the fact that they bring in this unique perspective that’s infused with history and family and community, and then it becomes hopefully a very powerful message.