“We Can’t Afford a Hollywood Marriage!” was the headline in the October 1933 issue of Hollywood magazine and, beneath it, Cary Grant and Randolph Scott were pictured whistling as they did the dishes together at the kitchen sink and singing happily at the piano in their living room. In an accompanying interview, they admitted that they earned high salaries by ordinary American standards but also insisted that stardom shackled them with unusual burdens. “If I were a young doctor or lawyer in some other place, drawing the same salary, I could afford to marry easily,” Grant said. “It’s what Hollywood demands of a motion-picture personage that hurts. It’s a car and driver, a house in Beverly Hills, and a beach house in Malibu. It’s the front you’ve got to put up.” Scott chimed in, saying, “Yeah, and if I were married, it would be trips to Europe and trips to Palm Springs and Lord knows where else — all first class. What Cary and I want to do is to hop a tramp steamer for the South Sea islands, and can you imagine a woman coming along on a trip like that?”

Cary Grant and Randolph Scott really did live together, beginning 1932 when they were both up-and-coming stars at Paramount Studios, and continuing off and on through 1940, when they were major stars, earning enough money to share a large beach house on a prime stretch of sand in Santa Monica. Although other male stars of the 1930s shared homes — James Stewart and Henry Fonda, Errol Flynn and David Niven — none had whole publicity campaigns built around their relationship. This is one reason why modern commentators often assume that Grant and Scott were lovers rather than roommates. There are so many pictures of them, looking so handsome and happy together, that their affair appears to be a very appealing, very well-documented truth.

Yet the stories printed about stars in the film fan magazines were as fanciful, and often as downright fictional, as any of the films that the stars made. In the U.S., there were a dozen or so of these magazines in the 1930s, and they were read by millions of people. Judging by the advertisements, most of the readers were women, seeking a measure of glamour and escapism without having to visit the movie theater.

The magazines were not scandal sheets but instead portrayed Hollywood stardom as a lifestyle free of ordinary responsibilities and conventions, even if it did come with expensive obligations such as a chauffeur and first-class travel. Stars were not asked to talk about acting or their careers but instead to reveal their homes and cars to the camera and to comment on their travel plans and their romances. Hence, Grant and Scott were cast in these articles as Hollywood’s most eligible bachelors, and the home they shared was dubbed “Bachelor Hall,” an “Eve-less Eden” where men never had to grow up but could remain youthful and wholesome forever.

Paramount’s publicists came up with the stories as a means of promoting two up-and-coming stars at once. By 1933, Grant had appeared in two box-office hits, She Done Him Wrong and I’m No Angel, but both were Mae West vehicles in which he was barely noticed. Scott, too, made a lot of films without much success, including the flop Hot Saturday, in which he and Grant vied for the affections of star Nancy Carroll. The publicity, it was hoped, would build some interest in them and in their films.

Across the articles, they are portrayed as bachelors desperately in need of a woman’s help and care. For example, in the fan magazine Modern Screen, they revealed their favorite seafood recipes (crab and asparagus salad for Grant, baked lobster for Scott) to readers, who presumably might practice making the dishes for them. On the radio, they emphasized this by advertising Betty Crocker prepared foods, speaking about how useful instant-food products were to men who had no wives to cook for them.

When Grant married Virginia Cherrill in 1934, an article in Modern Screen reassured readers that the two men were “still pals.” “Not even a wife could separate Cary and Randy,” it read, “but then, Virginia wouldn’t want to.” When Grant and Cherrill divorced a year later, Grant and Scott moved into the Santa Monica beach house they would live in for the next five years. During this time, Grant had lengthy relationships with actresses Mary Brian and Phyllis Brooks, while Scott married his childhood sweetheart, the heiress Marion duPont, and, after they split up, he dated the “jungle princess,” Dorothy Lamour. None of the people who knew them at this time thought that the two men were anything other than straight.

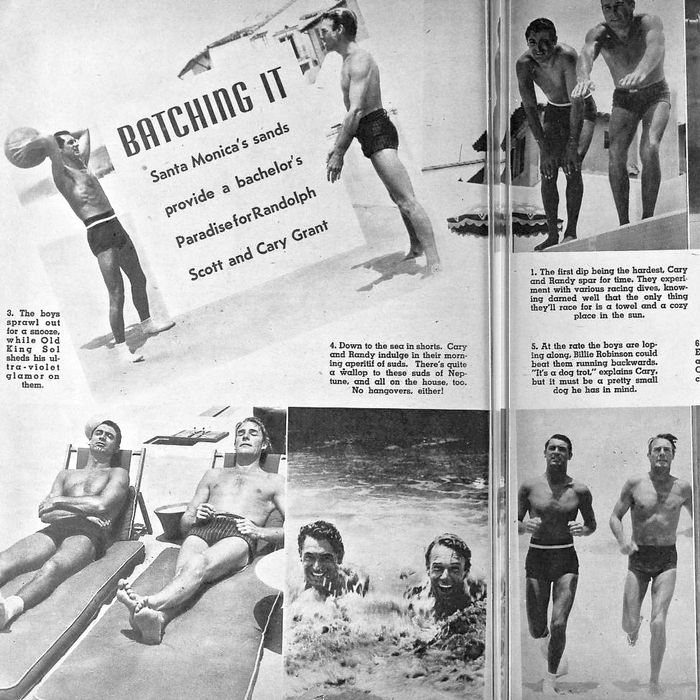

Grant’s friends have recalled a busy social scene at the beach house, especially on Sundays, when filming stopped at all of the studios and filmmakers mixed at casual parties. Grant’s own home movies show these bustling, all-day parties, and the deep dark tan he developed spending the day in the sun with his friends. The fan magazines, however, portray life at the beach house in a very different way. They picture Grant and Scott doing everything together — sunbathing, swimming in their pool, tossing a ball, and running on the beach — entirely alone. Similarly, inside the house, they are pictured eating, playing backgammon, reading, and playing with the dog (a Sealyham terrier named Archie).

Today, these images look like portraits of a very happy gay marriage, and many contemporary commentators assume that they really are candid snapshots of the stars’ private lives. Some of Grant’s biographers have written that the photographs were leaked to the press or published just once by mistake. Others writers, commenting more widely on Hollywood’s oppressively closeted traditions, present the photographs as evidence of a hidden gay history.

While there is no doubt that Hollywood has a hidden gay history, it is very unlikely that these photographs figure in it in the way that contemporary commentators suppose. In fact, the photographs were not hidden at all. Cary Grant’s collected papers (held at the Margaret Herrick Library in Beverly Hills) include dozens of scrapbooks filled with publicity clippings from every stage of his career. The scrapbooks show that the images of Grant and Scott at home together were published over and over again, across a range of fan magazines, in the mid-1930s. Furthermore, Paramount’s own archives (also held at the Herrick Library) reveal that the studio commissioned these photographs as a part of the continuing campaign to promote Grant and Scott.

If there is a gay perspective in the photos, it is likely due to the photographer, Jerome Zerbe, who was young, gay, and intent on taking a different approach to photographing stars. He eschewed the carefully lit, studio-bound glamour photography that was the norm in 1930s Hollywood, preferring to capture stars in shots that appear spontaneous and unposed, and therefore seem to be more intimate and revealing. Zerbe’s photographs of Grant and Scott perfectly exemplify his approach, but he also brought an unmistakable sexual frisson to these images.

This did not go unnoticed by Paramount’s publicists, and in some instances they thought it was too overt. In one shot, Zerbe framed Grant and Scott in silhouette on the terrace, with the sun setting in the distance behind them, as Scott lit Grant’s cigarette. In another, they were posed sitting closely together on the diving board in their bathing suits, with Scott’s hands poised to touch Grant’s shoulder, presumably to push into the water. The Paramount publicists marked these as “kill shots” — that is, photos that should not be published. However, the studio was happy to distribute the other photographs and to have them accompany articles with headlines such as “Movie Bachelors at Home” (in Screenland) and “Batching It” (in Modern Screen).

Although Grant and Scott were both in their 30s, the articles refer to them not only as bachelors but as “the boys” and “best friends” — terms that emphasis their eligibility for marriage and also contextualize the readers’ gaze, suggesting that the photos can be admired in motherly or sisterly manner rather than in an openly sexual manner. Beefcake was too vulgar for magazines so heavily invested in glamour, but these playful, tasteful images suited the magazines perfectly.

In later years, neither Grant nor Scott ever commented on this publicity campaign and what they thought of it, but they may have been sharing an inside joke about it in the only other film that they made together, My Favorite Wife, in 1940. In their first scene together, when Grant sees Scott in a bathing suit at a swimming pool, his character is so awed by Scott’s physique that he has to mop his brow, and later in the film he continues to picture Scott at the pool in his mind. By this time, both Grant and Scott were well-known stars and could afford to laugh about the contrivances of their early publicity. It is likely, though, that they would have been surprised that Paramount’s very carefully staged publicity images were mistaken for everyday snapshots, and even more surprised that modern readers evidently find them as captivating as readers in the 1930s did.

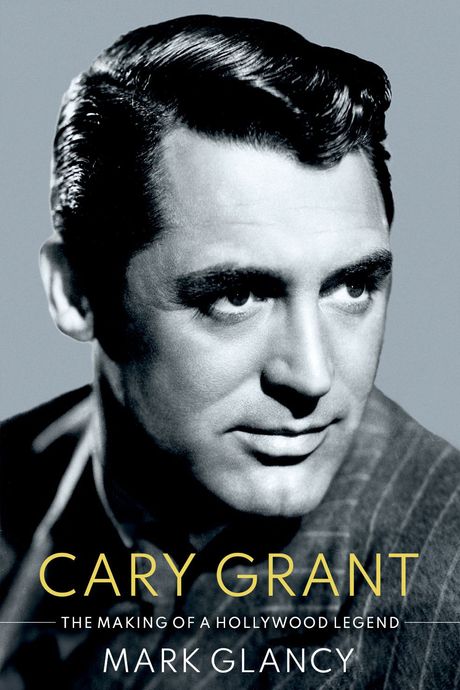

From Cary Grant, the Making of a Hollywood Legend, by Mark Glancy. Copyright © 2020 by Mark Glancy and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.